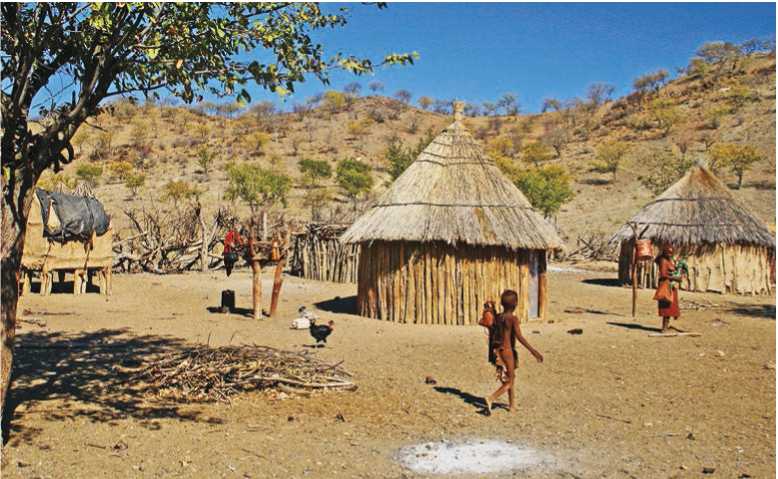

The region from southern Angola to central Namibia is dominated by several animal-based Bantu societies. Due in part to their isolation and the rugged territory in which they lived, the Himba have maintained their nomadic life. The relatively autonomous family units have a headman who is a grandfather or family elder. Cattle, as is common, are not used primarily for meat, but as a form of wealth and are particularly significant during marriage. A wife can cost the man up to four cows. Himba men can have more than one wife depending on their wealth. At the base of Himba belief is a supreme being called Ndjambi-Karunga or Mukuru, who is generally regarded as the creator of all things, born by the fire sprinkled by the lightning-shooting Omborombongo tree (holy tree). A person passing this tree would put leaves rubbed against their forehead into the holes of branches.3 Mukuru, although known for his kindness and as the provider of rain, is not a deity in the strict sense as no active religious worship is directed toward him. In contrast to this, belief in the existence of ancestral spirits is much more clear-cut. These spirits exercise an influence over their living descendants. As such, ancestral spirits mediate between man and Mukuru, a position that strongly demands the maintenance of harmonious relationships with the spirit world (Figures 15.8, 15.9, 15.10, and 15.11).

Figure 15.8: Himba village, Namibia. Source: © James Whatley (Http://creativecommons. org/licenses/ by/2.0/deed. en)

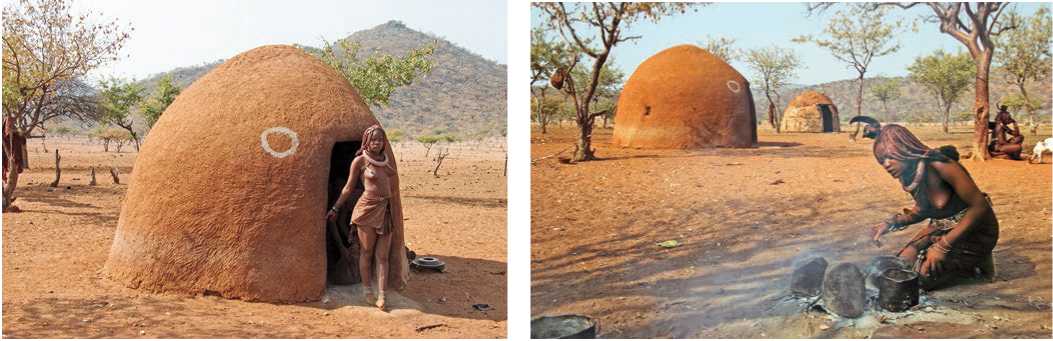

Figure 15.9: Himba village, Namibia. Source: © Hans Hillewaert (Http://creativecommons. org/licenses/ by-sa/3.0/deed. en)

Figure 15.10: Himba village, Namibia. Source: © Yves Picq (http:// creativecommons. org/licenses/by-sa/3.0/deed. en)

Contact with ancestral spirits is made by means of a ritual fire that is kept burning twenty-four hours a day. Extinguishing the fire would indicate grave neglect on the part of the village-head because it symbolizes the contact between the living and deceased members of the family. The headman of the clan sits by the fire during the day and talks to the ancestors about problems facing the village or family. At night, his wife takes an ember from the fire inside the hut. In the morning this ember will be used to rekindle the sacred fire. The fire in the main hut is not kept burning during the day. Regular daily rituals are performed around the fire, of which the tasting of milk from the ritual cows is most significant. By this act, called okumakera, the village-head frees the milk from its ritual restraints, thus rendering it suitable for use by other persons (Figure 15.12a, 15.12b).

The ritual fire, called the okuruwo, may only be generated by means of ritual fire-sticks called ozondume, of which each lineage-head keeps a special set. The ozondume are round sticks that are twirled in shallow holes on a sofi:er wooden slab. Combustion emanating from these holes actually constitutes the particular fire of a patrilineal kin group (oruzo), which must be kept burning between the entrances to the main hut and the cattle enclosure. The fire is encircled by a number of stones, and beside it mopane wood is piled up for use in the okuruwo. The okuruwo itself consists of a single smoldering stump lying in the ashes, and it is only stirred into flame when important rituals are performed. Strangers are not allowed to pass between the sacred fire and the headman’s hut, nor may they pass between the cattle kraal at the center of the village and the sacred fire. If need be, guests must walk around the back of the hut. The headman’s hut is the only hut in the homestead that has an opening facing the fire. All other huts open away from the fire.

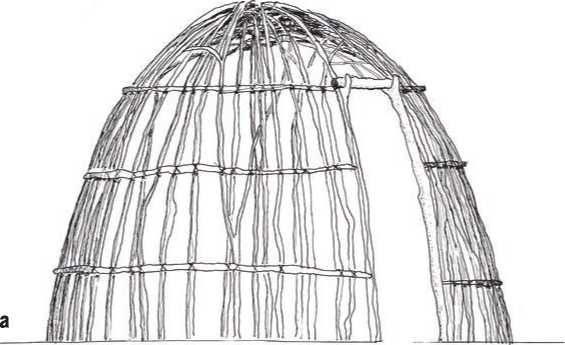

Figure 15.11: Himba village, Namibia. Source: © Yves Picq (http:// creativecommons. org/licenses/by-sa/3.0/deed. en)

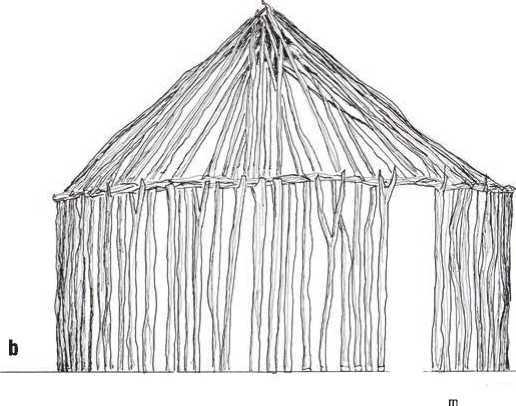

Figure 15.12a, b: Himba, Namibia, structural frameworks of huts: (a) type 1, (b) type 2. Source: Mark Jarzombek

While the fire was located at the center of each village, it is the location of the sacred tree associated with Mukuru that determines the camp layout. The fire is always placed to the east of the tree. The tree is consecrated with the blood of a game animal poured into a cut in the bark. Afi:er this the fire can be lit and the homesteads brought into being. The village is surrounded by a fence that is typically made of branches from the Mopane tree. In most homesteads there is only one opening in this fencing. At the center of the enclosure, or to its west, there is a second circular fence of branches, and a kraal for the cattle and goats. The headman’s hut is located farthest from the opening usually to the east with the sacred fire in front of it. His hut is called otjizero, which means place of taboos, because of the ritual items stored there. The whole area between the cattle enclosure and the main hut is in fact regarded as sacred. The huts for the rest of the clan are built toward the edges of the enclosure, which might have a diameter of about 150 meters. The preference of individuals is to be located near the high-status east of their respective camps. Specially constructed platforms serve as storage areas where things can be protected from animals.

The ritual fire cult is not unique to the Himba. It is shared by the Herero (Namibia and Angola), as well as by the Damara (Namibia), who are called “hunter-gatherers" and the Owam-bom (Namibia), who are akin to the Bantu, of whom they are descendants; this latter group pursues a mixture of animal and agricultural activities. Each developed a slightly difierent layout of the village, but the basic orientation strategies are quite similar.

Ideally, for the Himba, ancestors are commemorated every other year and during a fifi:een-day event, called Okuyambera (“approach to the deities"), in which a ritual homestead is built only for this purpose. There is no prescribed time for this to take place. It occurs when the ancestors give the headman a hint that such a ritual is necessary. It is set up like a regular settlement except that there is a special resting place for the elders who can meet in the shade of the tree next to a set of wooden stelae that represent the ancestors and that are sacred. Nearby there is a special place where ritually slaughtered meat is distributed.

Himba huts, circular in plan and domed or slightly conical, are constructed of branches and dried mud. There are two variants. In one variant thin poles are bent to form the dome. Horizontal bands of vines or thin twigs are tied to vertical poles that give the structure its integrity. There are two, sometimes three, bands. The whole is covered with mud. The area below the lowest band is sometimes left open for ventilation. A second version is constructed of more solid branches in the form of a vertical wall. A band at the top serves to hold the structure together against the pressure of the conically shaped roof. Construction is primarily women’s work and it is they who are considered the owners of the hut.

When a Himba dies, the body is wrapped and bound in the skin of cattle and placed next to the sacred fire. The first period of mourning lasts twenty-four hours or more, during which time cattle are slaughtered. The person is buried far from the village, and the horns of the slaughtered cattle are placed on the grave, usually mounted on a pole. In the case of a man, the horns are placed upright, for a woman the horns point downward. The slaughter ritual is difier-ent from slaughtered for meat consumption. In this case, the skull is severed from the body and the meat and skin removed. A hole of about a centimeter in diameter is hewn or drilled into the forehead, and the skull, smeared with ochre, is then displayed at the ancestral fire, before being taken in procession to the gravesite.4 The greater the number of horns on the grave, the greater the wealth and status of the individual. In the case of the death of a headman, the main hut is dismantled and parts of it are burned. The sacred fire is scattered, to be rekindled later from new branches. The headman is bound, wrapped in the skin of his favorite ox, and buried facing the rising sun in the east. His walking stick is broken in two and placed on the grave along with his sandals and the horn that he used for calling cattle. It is believed that the elder enters the afterlife accompanied by the cattle that are slaughtered during the mourning period. After he is buried, the clan returns to the homestead and a second period of mourning begins, lasting about a month. More cattle are slaughtered and their horns will be added to those already on the grave. The ancestors are contacted by burning the root of the omuhe shrub, and a purification ritual takes place.5

World History

World History