Caves and rockshelters have long been the focus of prehistoric and archaeological research, and many of the most archaeologically significant finds have been uncovered from them. Finds encompass remains of fossil hominins, which span a major part of the human record, including Australopithecus in South African cave sites (e. g., Swartkrans), various species of Homo and Neandertals from both Europe (e. g., Atapuerca, Spain; Tautavel, France; Neanderthal Cave, Germany) as well as the Middle East (Shanidar, Kurdistan; Qafzeh and Kebara, Israel). Furthermore, many cave and rockshelter sites contain abundant lithic, faunal, and floral remains within thick accumulations of deposits that permit archaeologists to detect long-term changes in technology, plant and animal exploitation, and site use through time. Striking examples of all of the above are Tabun Cave, Israel, with over 18 m of deposits that contain Lower and Middle Palaeolithic remains spanning over 200 000-300 000 years of human history (Figure 1). At Danger Cave in the Great Basin of North America, there is an extraordinary stack of well-preserved primarily culturally derived sediments spanning more than 10 000 years. Also, extensive and intensive occupation lasting from Late Palaeo-Indian through Late

Figure 1 TabunCave, Israel showing a thick sequence of sandy, silty, and anthropogenic deposits; Lower Palaeolithic deposits occur at the base and Middle Palaeolithic deposits are seen above the third step. The vertical nature of the deposits in the lower left is associated with subsidence of the deposits into a subterranean depression or swallow hole during the Lower Palaeolithic.

Archaic times is illustrated at Dust Cave, Alabama (Figure 2).

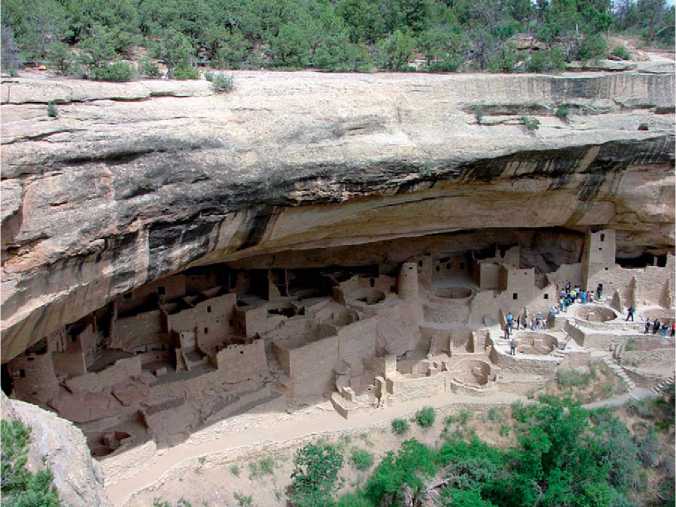

The deep interiors of caves are in total darkness and isolated from the outside environment. In contrast, cave mouths and areas under projecting rock ledges (rockshelters) have broad connections with the outside environment and are illuminated to some extent by sunlight. The degree of protection from the outside climate or weather depends on the size, configuration, and orientation of the rockshelter or cave mouth. For example, the deep, massive rock-shelters at Mesa Verde in southwestern Colorado provide considerable protection from the external environment (Figure 3). In contrast, the small Movie Draw Rockshelter in the Black Hills of South Dakota affords little protection (Figure 4).

At high altitudes in the Peruvian Andes, nearly all of the recorded archaeological sites are in caves because they offered shelter from the rain, wind, and cold nights. Pachamachay Cave at 4300 m (nearly 14 000 ft) above sea level has 33 superimposed layers of cultural deposits dating between 12 000 and 8000 years BP. Guitarrero, another high-altitude cave in Peru, contains evidence of human occupation between 10 500 and 2000 years ago, and a possible occupation layer was dated to c. 13 000 14C years BP.

Caves and rockshelters have been the focus of archaeological research concerned with the peopling of the New World, especially South America. Cave sites in the Peruvian Andes - including Telarmachay, Uchuma-chay, Lauricocha, Huargo, Guitarrero, Pachamachay, Pikimachay, and Panaulauca - have yielded finds suggesting, but not proving, that people were in the

Figure 2 Dust Cave, Alabama. Dust Cave presents a striking example of anthropogenic ashes and charcoal, interfingered with detrital clays, which have been remarkably well preserved because of the dry conditions.

Figure 3 Cliff Palace, Mesa Verde, Colorado. This 200-room Anasazi cliff dwelling is in a large rockshelter formed along a shale-sandstone contact.

Figure 4 Movie Draw Rockshelter, Custer State Park, Black Hills of South Dakota. This small rockshelter formed in sandstone has yielded a rich cultural record dating from c. 2000 to 700 BP.

Region as early as 20 000-15 000 BP. In eastern Brazil, the rockshelter at Pedra Furada has produced disputed evidence for human occupation over 30 000 years ago. Although pre-12 000BP ‘archaeological’ findings at many of the cave and rockshelter sites mentioned here are problematic, they have yielded unequivocal

Evidence for people in South America between c. 12 000 and 10 000 BP (see Americas, South: Early Cultures of the Central Andes).

Unlike most open-air sites, caves and rockshelters constitute distinctive archaeological environments in that they tend to be essentially closed systems.

Materials that are brought into the enclosed space tend to stay there, and thus they present detailed records of geological and human activities, although they can be subject to physical and chemical modifications. They provide a contrast to the situation of open-air sites, which are more prone to erosion or burial by processes associated with gravity, wind, or water.

The cultural deposits of dry cave and rockshelter sites generally yield well-preserved floral and faunal remains. For example, the earliest solid evidence for domesticated maize comes from the dry rockshelter site of Guilii Naquitz in Oaxaca, Mexico, where two maize cobs produced AMS radiocarbon dates of c. 6300 BP. The dry San Marcos and Coxcatlan rockshelter sites in the Tehuaciin Valley of Puebla, Mexico, have yielded well-preserved maize that is nearly as old as the maize from Guila Naquitz. In southern Peru, the dry rockshelter site of Asana has well-preserved faunal remains (mostly deer, camelids, and small mammals) dating back to c. 11 500 BP, plus a variety of floral materials, including tubers, mesquite pods, cactus fruits, and chenopod grains.

The recovery of well-preserved floral and faunal remains is not limited to dry caves and rockshelters in Mexico and South America. The earliest farmers in the mid-south of North America lived seasonally in rockshelters and also used them for dry storage of cultivated plants. Evidence for early (Late Archaic), domesticated, small-seeded plants has come from the Cold Oak, Cloudsplitter, and Newt Kash rockshelters in eastern Kentucky and the Marble Bluff rockshelter in northwestern Arkansas. At Salts and Mammoth caves in Kentucky, Early Woodland people unknowingly left a detailed record of their diet in the dry cave passages. Thousands of human coprolites are well preserved throughout the nearly 35 km of cave passages explored and mined for minerals (mostly gypsum and medicinal sulfates) between c. 2800 and 2300 BP. The coprolites, plus stratified archaeobota-nical remains from the mouth of Salt Cave, provide the most detailed record of an ancient agricultural complex known anywhere in the Americas.

The aridity of rockshelters also has resulted in remarkable preservation of perishable organic materials at sites in the Great Basin of North America. For example, several dozen sandals made from sagebrush bark fiber were found in Fort Rock Cave in southern Oregon. A fragment from one of the sandals yielded a radiocarbon age of c. 9000 BP. Two other Great Basin rockshelters, Lovelock and Humboldt in west-central Nevada, contained well-preserved nets, mats, cordage, twined and coiled baskets, cloth, and hides, with some of the materials dating as far back as 4500 BP. At Hogup Cave on the western edge of the Great Salt Desert of Nevada, cultural deposits dating to the Early Holocene and later times included the seeds of pickleweed, a plant native to the salt flats, and fragile remains of waterfowl and shore birds hunted at nearby salt marshes and small lakes.

Although cave and rockshelter sites are less numerous than open-air sites, they have played a very significant role in furnishing data on prehistoric human palaeoecology and evolution. They also have shed light on the timing of human arrival in the New World. Hence, cave and rockshelter sites merit attention from the archaeological community. It is important to understand how these geologic features form in the landscape and receive sediment from internal and external sediment sources. It is also important to recognize postdepositional processes that may affect the archaeological record at cave and rockshelter sites. Despite being relatively protected, caves, and especially rockshelters, are not always isolated from geomorphic and biologic processes that may reshape cultural deposits in these settings.

World History

World History