Fossils from a number of sites in Africa, Asia, and Europe, dated to between 200,000 and 400,000 years ago, indicate that by this time cranial capacity reached modern proportions. Most fossil finds consist of parts

24 Wolpoff, M. H. (1993). Evolution in Homo erectus: The question of stasis. In R. L. Ciochon & J. G. Fleagle (Eds.), The human evolution source book (p. 396). Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall.

Of one or a very few individuals. The fossils from Sierra de Atapuerca in northern Spain (pictured in the chapter opener), are the only ones to exist as a population. Dated to 400,000 years ago,121 the remains of at least twenty-eight individuals of both sexes and of various ages were deliberately dumped (after defleshing their skulls) by their contemporaries into a deep cave shaft known today as Sima de los Huesos (“Pit of the Bones”). The presence of animal bones in the same pit with humans raises the possibility that early humans simply used the site as a dump. Alternatively, the treatment of the dead at Ata-puerca may have involved ritual activity that presaged burial of the dead, a practice that became common after

100,000 years ago.

As with any population, this one displays a significant degree of variation. Cranial capacity, for example, ranges from 1,125 to 1,390 cc, overlapping the upper end of the range for H. erectus and the average size of H. sapiens (1,300 cc). Overall, the bones display a mix of features, some typical of H. erectus, others of H. sapiens, including some incipient Neandertal characteristics. Despite this variation, the sample appears to show no more sexual dimorphism than displayed by modern humans.122

Other remains from Africa and Europe dating 200,000 to 400,000 years ago have shown a combination of H. erectus and H. sapiens features. Some—such as skulls from Ndutu in Tanzania, Swanscombe (England), and Steinheim (Germany)—have been classified as H. sapiens, while others—from Arago (France), Bilzingsleben (Germany), and Petralona (Greece), and several African sites—have been classified as H. erectus. Yet all have cranial capacities that fit within the range exhibited by the Sima de los Huesos skulls, which are classified as H. antecessor.

Comparisons of these skulls to those of living people or to H. erectus reflect their transitional nature. The Swanscombe and Steinheim skulls are large and robust, with their maximum breadth lower on the skull, more prominent brow ridges, larger faces, and bigger teeth. Similarly, the face of the Petralona skull from Greece resembles European Neandertals, while the back of the skull looks like H. erectus. Conversely, a skull from Sale in Morocco, which had a rather small brain for H. sapiens (930-960 cc), looks surprisingly modern from the back. Finally, various jaws from France and Morocco (in northern Africa) seem to combine features of H. erectus with those of the later European

B

Neandertals. A similar situation exists in East Asia, where skulls from several sites in China exhibit the same mix of H. erectus and H. sapiens characteristics.

“Lumpers” suggest that calling some of these early humans “late H. erectus” or “early H. sapiens” (or any of the other proposed species names within the genus Homo) serves no useful purpose and merely obscures their transitional status. They tend to lump these fossils into the archaic Homo sapiens, a category that reflects both their large brain size and the ancestral features on the skull. “Splitters” use a series of discrete names for specimens from this period that take into account some of the geographic and morphologic variation present in these fossils. Both approaches reflect their respective statements about evolutionary relationships among fossil groups.

With the appearance of large-brained members of the genus Homo, the pace of cultural change accelerated. A new method of flake manufacture was invented: the Levalloisian technique, so named after the French site where such tools were first excavated. Flake tools produced by this technique have been found widely in Africa, Europe, southwestern Asia, and even China along with Acheulean tools. In China, the technique could represent a case of independent invention, or it could indicate the spread of ideas from one part of the inhabited world to another.

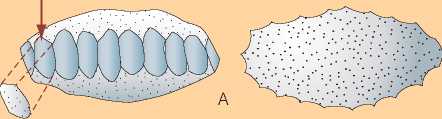

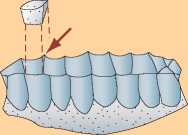

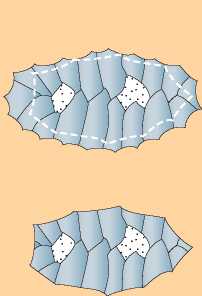

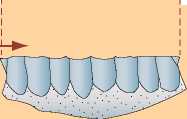

The Levalloisian technique initially involves preparing a core by removing small flakes over the stone’s surface. Following this, a striking platform is set up by a crosswise blow at one end of the core of stone (Figure 8.9). Striking the platform removes three or four long flakes, whose size and shape have been predetermined by the preceding preparation, leaving behind a nodule that looks like a tortoise shell. This method produces a longer edge for the same amount of flint than the previous ones used by evolving humans. Sharper edges can be produced in less time.

C

Figure 8.9 These drawings show side (left) and top (right) views of the steps in the Levalloisian technique. Drawing A shows the preparatory flaking of the stone core; B, the same on the top surface; and C, the final step of detaching a flake of a size and shape predetermined by the preceding steps.

With this new technology, regional stylistic and technological variants become more marked in the archaeological record, suggesting the emergence of distinct cultural traditions and culture areas. At the same time, the proportions of raw materials procured from faraway sources increased; whereas sources of stone for Acheulean tools were rarely more than 20 kilometers (12 miles) away, Levalloisian tools are found up to 320 kilometers (200 miles) from the sources of their stone.123

The use of yellow and red pigments of iron oxide, called ochre, a development first identified in Africa, became especially common by 130,000 years ago.124 The use

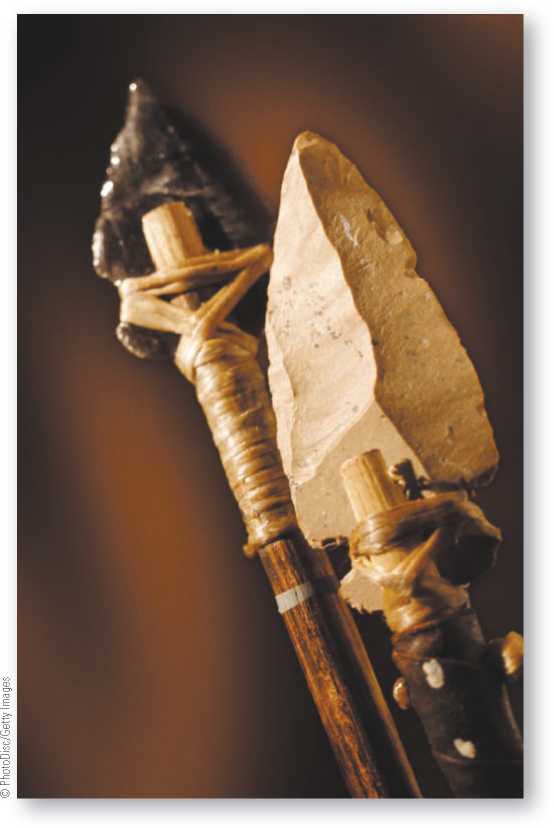

At about the same time the Levalloisian technique was developed, our ancestors invented hafting—the fastening of small stone bifaces and flakes to handles of wood. Hafting led to the development of knives and more complex spears. Unlike the older handheld tools made simply by reduction (flaking of stone or working of wood), these new composite tools involved three components: a handle or shaft, a stone insert, and the materials to bind them. Manufacture involved planned sequences of actions that could be performed at different times and places.

The practice of hafting, the fastening of small stone bifaces and flakes to handles of wood, was a major technological advance appearing in the archaeological record at about the same time as the invention of the Levalloisian technique.

Of ochre may signal a rise in ritual activity, similar to the deliberate placement of the human remains in the Sima de los Huesos, Atapuerca, already noted. The use of red ochre in ancient burials may relate to its similarity to the color of blood as a powerful symbol of life.

World History

World History