This magnificent fortress is one mile north of Oswestry. It encloses just over fifteen acres and has an elaborate defensive system of ramparts. Excavation shows that Neolithic people first occupied this dominating position during the fifth and sixth centuries BC, but the site was then abandoned. From the Iron Age through to the Roman period, it was continually occupied.

Within the traversing ramparts are two unique, huge, deep and mysterious annexes, which were once thought to be able to hold water. Other researchers have speculated that they may have been used to corral cattle. Both of these suggestions have now, however, been rejected.

This fort was once known as Caer Og rfan, the fort of Gogr an, who was the father of Guinevere, wife of King Arthur - a romantic notion but pure folktale.

Ty Mawr Hut Circle and Holyhead Mountain

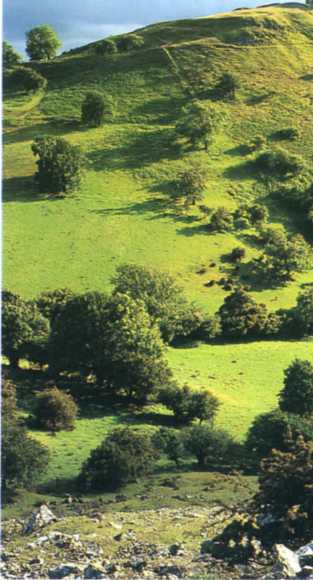

The Ty Mawr Hut Circle Group, also known as the Ctian Gwyddelod, 'TTie Irishmen’s Huts’, originally consisted of over fifty buildings covering between fifteen and twenty acres. Radiocarbon dating the artefacts excavated indicate that the site was in use from the late Neolithic period until the Dark Ages - some 5 or 6,000 years. There are eighteen distinct dwellings or farm buildings, however, but no more than two were in use at any one time. The occupiers were farmers who supplemented their diet by eating a variety of shellfish.

The hut circle group lies at the foot of Holyhead Mountain and the Iron Age hillfort of Caer y Twr. Seventeen acres are enclosed by a now veiy ruinous stone wall. These sites are adjacent to the South Stacks Cliff Nature Reser e, where numerous sea birds, including coughs, guillemots, razorbills, kittiwakes and puffins, linnets, stonechats, wrens, and white-throats, as well as more than twenty-five species of butterfly, can be found.

Dinas Bran

Dinas Bran is dominated by the ruin of a medieval castle, which commands the Vale of Llangollen. About 1,000 feet above sea-level, this surprisingly conical and naturally shaped hill was held during the eighth century-by Eliseg, the Prince of Powys.

Built on the site of an Iron Age hillfort, the ramparts are still visible. This site was once occupied by Bran the Blessed, who, in Welsh legend, was originally a god demoted after the advent of Christianity. He lived here during the Dark Ages, and this may well be the site of Bran’s stronghold from the tales in the Xlabinogion. If so, then this is the mysterious place, ‘Castle of the Grail’, from the Arthurian legends. Accordingly if this is the case, the Holy Grail - the cup that Christ used at the Last Supper - may well lie hidden here.

Another treasure awaits discover’: Merlin is supposed to have left a golden harp to be found by a blue-eyed boy with yellow hair accompanied by a dog with a silver eye.

Llangollen, named after the Celtic saint, Collen, is now-famous for the National Eisteddfod, w hich has been held here each July since 1947.

Brent Knoll

This isolated hill, surrounded by the Somerset Levels and bordered by the Bristol Channel to the west and the A5 motorway to the east, is the site of an Iron Age hillfort. The fort is roughly triangular, with a single rampart and ditch. On both the west and south faces the hillside has been artificially scraped to increase the gradient and defensive position. Probably the site of many skirmishes, it was in use throughout the Roman occupation of Britain, and right up to the end of the fourth centur>-.

According to folktale, Brent Knoll was the site of a battle between Yder, a Knight of King Arthur’s Round Table, and three local giants. Yder was sent ahead to prepare the way for Arthur and his army. However, when they arrived at Brent Knoll,

Arthur found that Yder and the giants were all dead.

The actual hillfort has been much denuded over the years through quarry ing for lias limestone and, in more recent times, the ramparts have been used as militar- trenches.

St Michael’s Church, an exquisite example of Norman architecture, nestles at the foot of Brent Knoll.

Chun Castle Morvah, Cornwall

High on Penwith Moor with spectacular views, the impressive remains of Chun Castle are still apparent. Originally over 250 feet in diameter with walls eighteen feet high, this hillfort is entirely built of stone and would have once dominated this wild and windy position.

Occupied from the third century BC through to the Dark Ages, this Iron Age hillfort has been much modified. It now encloses a stone-clad well and several courtyard houses. The double entrance was cleverly realigned during the Dark Ages to provide a staggered entrance, exposing an intruder’s unshielded side to the defenders. Just who those intruders might have been is open to speculation, perhaps marauding Irish pirates.

In the eighteenth century Chun Castle is recorded to have walls that were fifteen feet high. Then, during the nineteenth century when much of Penzance was built, this site was plundered for building material. Madron Workhouse, for example, was built from these stones.

Cam Brae lies above the former mining town of Redruth, once famous for its forest of smoking chimneys sprouting from the engine houses that provided the power for the mining shafts.

The Cam Brae prehistoric site encompasses forty-six acres. From about 3,900 BC huge stone ramparts enclosed a village occupied by over 200 people, who were peacefully settled until their community was attacked and burnt down. Archaeologists have found more than 700 arrow heads. In 1749 two hoards of Celtic coins from south-east Britain and Gaul dating from the late Iron Age were excavated.

Cam Brae Castle’s origins are medieval. It was first recorded in the fifteenth century, and was probably built by the Basset family and used as a chapel and, later, a hunting lodge. It has been enlarged over the years and is now a restaurant, the granite boulder being an integral part of the building.

According to folktale, a giant named Bolster lived and fought an endless battle with another giant on Cam Brae. His strength was such that he could hurl the enormous granite boulders about, and his stride was so great that it took him just one step from St Agnes Beacon to Cam Brae.

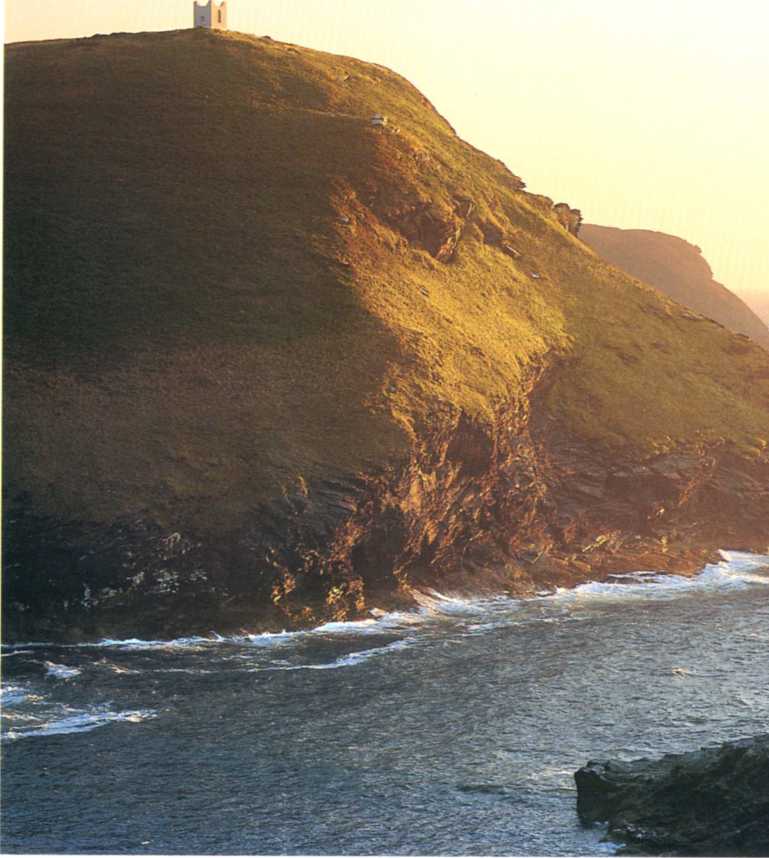

Willapark

Boscastle, Cornwall

Willapark and its natural defensive position was typical of numerous Iron Age promontory forts built by Celtic tribesmen. A huge single bank and ditch were dug across a narrow isthmus, which gave them a secure cliff castle. Now surmounted by a whitewashed look-out tower, depicted by Turner in 1827, it has variously been described as a ‘pleasure house’ and a ‘prospect house', and in old maps and guide books it is shown as an obser ator>’.

To the east of Willapark on Forrabuiy Common there are the so-called Forrabuiy Stitches: fort - two strips of individual land, divided only by low banks that early Celtic farmers cultivated separately. Tenants individually cultivated their strips, from Lady Day (25 March) to Michaelmas (29 September). Thereafter the land went into common usage until the following Lady Day.

This land is now managed and owned by the National Trust, and during the spring and summer it is ablaze with wild flowers.

St Michael de la Riipe Church

The church of St Michael de la Rupe is situated on the very western edge of Dartmoor and adjacent to an Iron Age fort, on an eroded cone of volcanic lava. This tor, 1,000 feet above sea level, commands spectacular views across the broad and arable plains, south to Tavistock and west to Launceston. Brentor comes from the Celtic word ‘Bryn’, meaning hill or mount.

St Michael de La Rupe, St Michael of the Rock, is one of the smallest churches in the countrc' and was built by Robert Giffard, the Lord of the Manor of Lamberton and Whitechurch in about 1130. As with many ancient Norman churches it has seen numerous additions and alterations since its humble beginnings. Despite the rugged climb over often slipper}’ and steep, grassy banks, ser ices are still held in this wind - and rain-battered church each Sunday at 6.30pm from Easter until September.

Legend has it that the devil moved this tiny church to the top of the tor from safer ground below. St Michael, on completion of the building, beat off this evil spirit, hurling rock after rock down upon him.

Gurnards Head Cliff Castle Treen, Cornwall

Gurnards Head Cliff Castle is protected by the usually frantic Atlantic Ocean and a sheer cliff wall. For an invading force to berth a boat and then scale the sea wall would have been an almost impossible task. On the landward side at the narrowest point of this headland, Iron Age Celtic people built three, now ruined, stone ramparts, sixty metres long, and accompanying ditches. These ramparts are slightly out of alignment and form a staggered entrance.

During excavations in the 1930s, it was discovered that the inner ramparts had been built to provide steps, possibly for defensive sling shot use, similar to some Breton sites.

On the sheltered east side, more than ten Iron Age house platforms have been identified, and these were re-occupied during the Romano-British period. Gurnards Head Cliff Castle is approached by a track leading from the diminutive farming settlement of Treen, which also has associations with early Celtic, Romano-British and prehistoric settlement sites. In some cases, these can be found among the original Iron Age Celtic field pattern systems. Very little has changed here over 2,000 years.

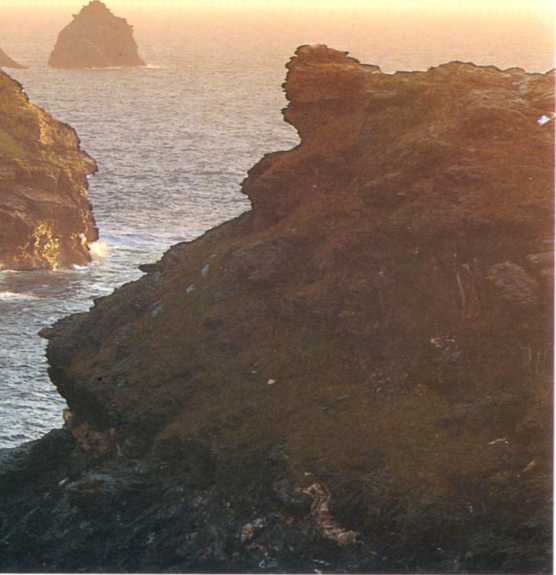

Kenidjack Castle St Just, Cornwall

A high, natural central spine of the rock and a triple rampart, makes this Iron Age hillfort an almost impregnable stronghold. An ancient trackway used for transporting tin and copper leads to the cliff castle from the cove below, which was once rich in minerals.

Julius Caesar wrote complaining about the difficulty in defeating these Celts, who took up a defensive position from within their cliff castles. He complained that attack from the seaward side was hazardous - at low tide it was impossible and at high tide, due to the steepness and the clever defensive network, attack was also difficult. When the defenders felt an onslaught from the landward side was imminent and impossible to beat off, they would gather their possessions and embark into one of their massive oak boats, moving off to another cliff castle further along the coast.

R

Drumadoon

Nr Blackwaterfoot, Isle of Arran, North Ayrshire

Drumadoon, the name means ‘hill of the fort’ is the largest Iron Age hillfort on Arran. Spectacularly situated, the massive enclosure of nearly twelve acres looks across Drumadoon Bay to Blackwaterfoot, with Kintyre to the west.

The natural sea cliffs offered protection from invaders, while to the landward side a ver>' ruinous single stone wall provided protection and shelter. A single Bronze Age menhir still stands, though surprisingly for such a large fort ver>- few hut circles have been found.

Torr a’ Chaisteal Dun Nr Corriecraine, Isle of Arran, North Ayrshire

This natural knoll may well have first been fortified 1,800 years ago. The square top contains a three-metre-thick circular stone wall of a ruined dun. Here, an extended family once lived and were undoubtedly both farmers and fishermen. These duns are often only slightly larger than a hut circle, and share many of the same architectural features of the much larger defensive forts known in northern Scotland as brochs. Torr a' Chaisteal looks out over Kilbrannan Sound, named after the sixth-centur>-Celtic saint, Brendan. When excavated during the nineteenth centur’ it revealed little - some human bones, a grinding stone and some haematite iron.

Many duns were re-occupied through the centuries, certainly up to the Dark Ages, and it is quite likely that this one was too. If so, it may well have been used by Gaelic-speaking Irish folk called Scotti, who invaded and established themselves in Arg) le 1,500 years ago.

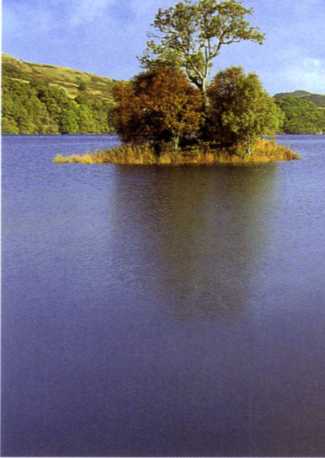

Crannogs, Loch Awe and Loch Nell

These small, circular islands, now a hundred yards into both Loch Awe and Loch Nell, were once the homes of lake-dwelling families. There are known to be about 400 crannogs in Scotland, but since Scotland has more than 30,000 lochs there is every chance that more will be discovered. There have been no discoveries of crannogs in England and only one in Wales.

They are essentially single family lake dwellings that were popular from the early part of the Iron Age until after the Roman occupation. However, there is now new evidence that some crannogs were first occupied as early as the Neolithic period, while others are known to have been in use up until the seventeenth century.

The foundations were built by adding boulders to a natural

Rocky outcrop in a lake, which were then filled in with loose stones. From that base a wooden stilt house was constructed, probably with a reed thatch, as a sort of water-borne round house. Crannogs were attached to the land by a jetty. They were a popular form of dwelling, primarily because they afforded security from attack by both man and beast. Additionally, they were relatively pest-ffee and afforded an excellent fishing platform. According to recent archaeological evidence, crannog dwellers from the late Bronze-Age and early Iron Age kept cattle, sheep, goats and pigs. They were farmers who built near fertile land.

World History

World History