Humans arrived at Japan and the Philippines some 40,000 years ago, and they spread to the various islands, producing a complex cultural and linguistic map. They lived of fishing, hunting, and plant-gathering, but did not make settlements of any size or duration. The archeological record changes considerably beginning about 3000 bce, when, beginning with Taiwan, the various islands east of the Asian landmass, began to receive a host of newcomers, known as Astronesians, who were consummate horticulturalists, arriving on the shores with a predetermined cultural and agricultural package. At the core of the package was not only the art of ceramics but also a host of remarkable plants that were already circulating through the region. Taro and bananas were probably first domesticated in Papua New Guinea as far back as 8000 bce, with taro preferring swampy soil and bananas sandy soil. Breadfruit (Artocarpus altilis) was also probably first cultivated in northwest New Guinea, beginning around 3,500 years ago. The coconut was an even more ancient plant, requiring little in the way of agricultural tending. It was native to the area from Melanesia to south India. There was also sweet potato or yam, which was not native to Southeast Asia. How it came to be integrated into this food package is a mystery. Did it arrive somehow from South America, or did it spread through Chinese traders? No one knows for sure, but at 2000 bce it was already being loaded onto canoes along with the other plants by the intrepid sailors of the south Pacific.1 All these plants had, nutritional, religious, and symbolic value. Breadfruit, for example, is one of the highest-yielding food plants in the world, with a single tree producing up to two hundred or more fruits per season. When cooked, the taste of the fruit is described as potato-like, or similar to fresh-baked bread. Ripe breadfruit becomes sweet, as the starch converts to sugar and can be made into a fermented drink. Its milky juice is an important element in the caulking used by the boat makers. Coconut fronds were used for sails and clothings and its bark for rope. Pandanus, a palm-like tree that grows throughout the South Pacific, provides materials for housing; clothing, textiles, mats, food and medication, fishing, and ritual events.

Soil conditions played an important role in determining which plant could flourish where. Some islands like Belau (Babeldaob Island), in the western Pacific Ocean, were ideal for taro. The Trobriand Islands (officially known as Kiriwina Islands) were ideal for yams. Other islands with more sandy soil allowed locals to specialize the growing of coconuts and bananas. The Maluku Islands have mostly pOdsol and the acidic oRganosol, neither of which are good for agriculture, but are ideal for nutmeg and cloves, for which they are famous. Once trade began to flourish in the South Pacific, islanders traded these spices for rice and foods. Rice initially played a minor role compared to taro and breadfruit as it grew best only where there was andosols, which could be found in parts of Japan, the Philippines, and Indonesia.

The intelligence of these horticulturalists is evident everywhere, from the remarkable terraces of Palau, the origin of which are still unknown, to as far east as Hawaii. Cultivators there had to cope with a marked windward to leeward dichotomy in rainfall distribution. The wetter,

Northern, windward side was used for taro fields in the upper parts of the valleys; the lower and middle parts of the valleys were used for seasonal crops like sweet potato. There were also extensive plantations of breadfruit trees, impressive even to Captain Cook who landed on the island in the 1770s. Hamlets were placed on the drier slopes. The fields are particularly striking in Kohala and Kona where they cover some 200 square kilometers and are still partially visible on the slopes.

Obsidian and basalt for axeheads and azdes were another driver of the Pacific economy. Azdes were used to make canoes and other items, but they also served since the most ancient of times for ceremonial purposes as symbols of status. For the Trobriand Islands, azdes are standard wedding gifi:s. One azde quarry was on Tutuila Island (Samoas). Hawaii was the site of several important stone adze quarries, such as the Mauna Kea Adze Quarry on Hawaii Island, the largest stone tool quarry in all of the Pacific. Located at 12,000 feet near the summit of Mauna Kea (“White Mountain”), the workers had to endure freezing temperatures, snow, and even altitude sickness.

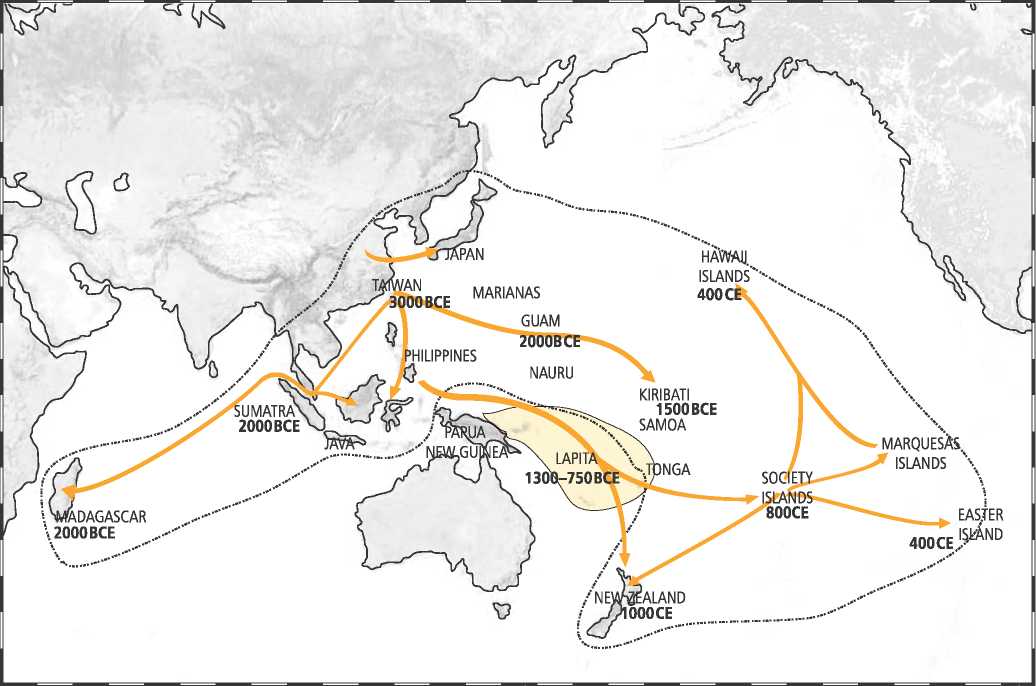

Figure 14.1: The peopling of South Pacihc and Indonesian Islands. Source: Florence Guiraud

The basic canoe that early travelers used was a dug-out log with an attached balancing outrigger which was kept to the windward. Smaller versions were fast and highly maneuverable. When Ferdinand Magellan arrived in the South Pacific in 1521, the Spanish sailors were amazed at the “flying ships” that flocked around them by the dozens as they approached land. Islanders also made boat hulls of planks lashed together and caulked. In the southward expansion, as the gaps between islands grew from tens of miles at the edge of the western Pacific to hundreds of miles along the way to Polynesia, and then to thousands of miles in the case of voyages to Hawaii, oceanic colonizers developed great double-hulled vessels, some reaching to 20 meters in length, capable of carrying colonists as well as all their supplies, domesticated animals, and planting materials. The Tahitians used their fleets for warfare, with warriors leaping from canoe to canoe and fighting on platforms. How the islanders navigated

Is still not known for sure, but they were highly attuned to the direction, size, and speed of ocean waves, to the colors of the sea and sky, as well as, of course, to the movement of the stars. A small boat might take a day or so to construct. Larger boats, with sails, rigging, and equipment could take up to a month. Wood was carved out of the log with an axe-head made from sharp tridaca shells.

The Lapita culture (1300 bce-750 bce) played a key role in the initial phases of this development. Originating probably on the island of Melanesia, the Lopita learned that many of the islands of the South Pacific were basically uninhabitable if they were not quickly and drastically modified by horticultural efibrts. Native terrestrial mammals (other than bats) were not to be found east of the Solomon Islands and even snakes were rare. Within four hundred years the Lapita had spread over a vast set of unpopulated islands, from the Solomon Islands, Vanuatu, and New Caledonia, to Fiji, Tonga, and Samoa, carrying with them some twenty-eight difi'erent plant species. Though fishing was a key component of their lives, they identified themselves as planters. The Proto Oceanic word for “ancestor” (*tumpu) derives from the word *tumbuq, which means “to grow.” Some groups took the awe-inspiring voyage due east, sailing against the prevailing tradewinds to cross 850 kilometers of trackless ocean to the Fiji archipelago. When colonizing a new area in this way, a group would leave as a team, carrying not only their provisions, but their entire cultural package of seeds, nuts, trees, and animals. On the ocean, the boats served as a floating village until they arrived and set to work on transforming the landscape to suit their needs. Cultivation included a combination of orchard gardens with tree gardens situated near or around the village with shifting cultivations cut annually from the forest or from the second-growth forest. Irrigation was not used, but the slope of the land and the nature of water drainage would have been well-studied. All of this required a politically complex chiefdom society that could organize and control the settlement’s activities. Smaller islands had a single chief, whereas on larger islands with multiple clans, one clan was seen as preeminent. Islands were not autonomous. The settlement of Talepakemalia, one of the early settlements (1500-1400 bce) shows that islands made shell fish hooks, beads, and other objects to trade for the many things that they did not have, such as basalt rocks, needed for cooking, chert and obsidian needed for axes and clay pots.

Over time, in some places, islands became regional powers, such as the Kingdom of Tonga, which comprised 176 islands scattered over 700,000 square kilometers of ocean. It is thought that the first settlers came around 900 bce. The chiefs built platform burial structures, twenty-two to twenty-eight in all. The grandest is Paepae o Tele‘a (“Tele‘a’s mound”), impressive in its engineering and joinery, with 8-foot-wide coral slabs neatly fitted one end to the next. The village to the west was protected by a ditch, which contained the numerous house platforms for the chiefs, clan members, and priests. The compound was entered through an impressive gate, Ha‘amonga ‘a Maui, constructed from three coral limestone slabs, and is up to 5.2 meters high, 1.4 meters wide, and 5.8 meters long, it was built at the beginning of the thirteenth century. The human impact on the natural environment was not always benign. At one site, Talepakemalai, 500 kilometers north of the colonists, who arrived around 1500 bce, lived on stilt houses just ofi the coast with ramps connecting the shore. The forest was cut down and replanted with fruit and coconut trees and the ground turned into gardens. By 800 bce, erosion had set in, collapsing the sand onto the beach and forcing the inhabitants to move farther out, with the process continuing so much that today, the site is several hundred meters from the shore.2

The last major region of Polynesia to be settled was New Zealand, which saw the arrival of settlers, around 1000 ce, who created the distinctive Maori culture. The island had the advantage of being a prime source for obsidian and greenstone, both of which were essential for ritual exchange. To the north, one finds the traditional horticultural package of yams, taro, and gourds, though it was not tropical enough for bananas and coconuts. Even so it still required great ingenuity to grow the plants that had been brought. Underground storage pits had to be built to preserve the yams through the winter. To the colder south, where horticulture was not possible, islanders lived entirely by birding, fishing, and gathering.

World History

World History