The two-wheeled chariot was probably introduced to Celtic Europe from Western Asia. In the Near East, the fast, light, manoeuvrable chariot is associated with cultures from the mid-second millennium BC.97

In the seventh and sixth centuries BC, some of the earliest Iron Age warriors were buried with four-wheeled wagons or carts (see p. 68). They were interred in wooden mortuary chambers, beneath large barrows. Hochdorf in Germany is a good example of this tradition; Vix in Burgundy is another.98 Representations of such carts are depicted on seventh-century rock carvings at Camonica Valley. The horses themselves were not usually buried, though exceptionally they might be slaughtered and buried with their dead chief, but sometimes three sets of harness are found in these princely graves, as if two were for the wagon team and the third for the chief's own charger. The yokes found at Hradenin in Czechoslovakia provide a particularly rich example of such harness. These four-wheeled wagon-burials were gradually replaced by the interment of light, twowheeled chariots, in the Rhineland, the Marne and elsewhere in France and then in Britain. Chariot-burials occur too in eastern Europe, in Hungary and Bulgaria.99

In the La Tene phase of pagan Celtic tradition, the two-wheeled chariot was employed in warfare, in parades and displays and in burial of an aristocratic warrior-elite. In Gaul, chariotry was practised until the second century BC, but in Britain, where it persisted much longer,

Figure 4.13 Female charioteer driving a human-headed horse, on a gold coin of the Redones, first century BC, France. Diameter 2cm. Paul Jenkins.

Caesar was surprised to see chariots operating in the mid-first century Bc. ioo The archaeological evidence consists of iconography, the remains of chariots and their fittings, found in such deposits as Llyn Cerrig Bach, and, above all, from the chariot-burials, to which I will return.

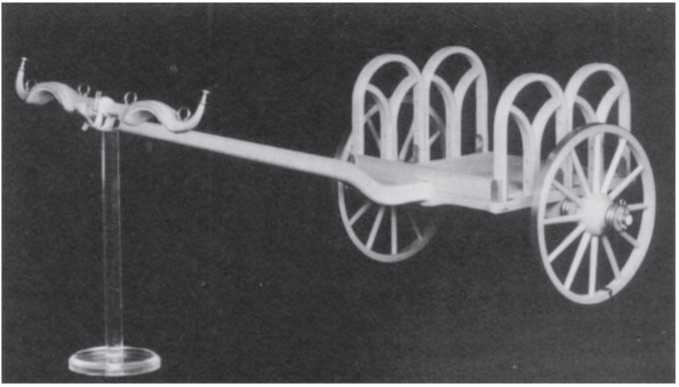

Hellenistic reliefs, at places like Pergamon in Asia Minor, represent Galatian chariots among the Celtic trophies depicted on triumphal arches.101 From these images and from actual remains of chariots, it is possible to piece together a reconstruction of a typical Celtic Iron Age chariot. The vehicles were made of iron, bronze, wicker and wood, built to be as light and agile as possible; they were drawn by two pony-like beasts. The harness was richly decorated with bronze ornament, sometimes inlaid with coral or enamel. To allow the charioteer fine control over his horses, the reins passed over a wooden yoke through a series of bronze rings or terrets. The bridge-bits or snaffles contained three main elements: a central bar with rings at each end. A reconstruction in the National Museum of Antiquities of Scotland shows the warrior standing in the chariot armed with his spears, while the charioteer squats in a crouch for greater stability and control, holding the reins.102 As well as spears, a warrior might be equipped with a long iron sword or a sling. Bows and arrows seem to have been used only rarely.103

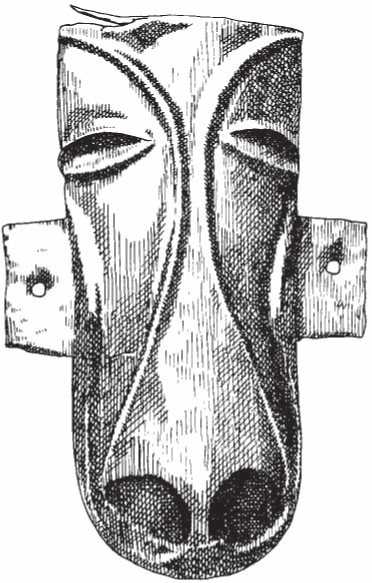

Indirect evidence for chariot warfare exists, independent of the vehicles themselves. Barry Cunliffe104 has suggested that the entrance courtyard of the east gate of Danebury could have been a chariot park. In addition, the site contains corral areas which would have made good pasture for chariot-ponies. Some fine bronze fittings found here could well be from chariot-pony harness. At the Brigantian stronghold of Stanwick, Yorkshire, a mount in the form of a schematized horse could have been a chariot-fitting (figure 4.14): it is a superb example of Celtic art, which captures the essential spirit of a horse's face in a few brilliantly modelled lines.105

It is the chariot-burials which provide a fascinating insight into the Celtic chariot-warrior and the rituals associated with his death. The tomb of La Gorge Meillet (Marne) was discovered in 1876: it consisted of a pit about 1.7 metres deep, dug into the chalk subsoil and containing a twowheeled chariot decorated with rich bronze fittings inlaid with coral. The vehicle had been buried with the body of a warrior, who had been laid out on the chariot-platform, with his weapons on the floor beside him. He was a young aristocrat who wore a gold bracelet and was accompanied by his long iron sword, four spears with iron blades, and a bronze helmet. Provision was made for the dead man in the afterlife or for the Otherworld feast: he had eggs, a fowl, joints of pork and a knife to eat them with; and a superb Etruscan-made flagon held his wine. Another chariot-burial, at Somme-Bionne (Marne), contained similar

Figure 4.14 Bronze mount in the form of a horse-mask, first century AD, Melsonby, Yorkshire (originally from Stanwick). Height: 7.5cm. Paul Jenkins.

Remains of an elaborate feast, including joints of wild boar, pig, duck and a peculiar deposit of a number of frogs placed in a pot.106 This burial dates to about 420 BC.

Rare examples exist of the interment of horses in a chariot-grave. At the end of the La Tene period (first century BC), two tombs were built at Soissons and elaborate rituals took place: in one burial, the chariot was found with the dead man, accompanied by what resembled a funeral cortege (figure 5.8): the two horses for the chariot were present but in addition there were two bulls, two goats, a ewe, a dog and some pigs. In a second Soissons grave were the remains of a chariot, an inhumation, two horses, two oxen, two goats, three sheep, four pigs and a dog. In both tombs the horses were small and apparently not sufficently robust to pull the heavy carts implied by the surviving fittings. Like the horses, the other beasts were all buried whole and had therefore not formed part of the funeral feast. They were presumably sacrificed in honour of the dead men,

Figure 4.15 Reconstruction model of a chariot, based on fittings from Llyn Cerrig Bach, Anglesey. By courtesy of the National Museum of Wales.

Who must have been important members of their community. This high status is perhaps implied also by the slaughter of the horses themselves, which, though of considerable value, were given up to the dead.107

In Britain, the chariot-burials of East Yorkshire do not normally contain the horse team itself, but occasionally the animals are present, as at the King's Barrow, where the body, chariot and a pair of horses were all interred.108 A pair of rich burials at Garton Slack was discovered in 1984 during gravel-digging. Here, a male and female of high rank were each interred with a dismantled chariot. The man was a warrior, who was accompanied by his sword in its scabbard, seven spears and a fragmentary shield; the woman's grave was very lavishly furnished, with precious bronze objects such a mirror and a cylindrical container which may have been a work-box.109

Uses of chariots in war: the ancient sources

As we have seen, the Continental Celts used chariots until the second century BC: various Mediterranean commentators on the Celts remark on this 'barbarian' form of warfare and display. Athenaeus110 speaks of the Celtic chieftain Louernius, who rode in his chariot over the plains, distributing gold and silver to the thousands who followed him. Bituitus, the king of the Arverni was displayed in the Roman triumph of 121 BC in multicoloured array, riding in a 'silver' chariot 'exactly as he had fought'.111 Diodorus Siculus comments on the Gauls thus: 'for their journeys and in battle they use two-horse chariots, the chariot carrying both charioteer and chieftain.'112 He goes on to describe how, when they met the enemy's cavalry in battle, they cast their javelins and then descended to fight on foot with their swords. The chiefs would stand in front of their army and chariotlines, challenging their opposite numbers. The chariot-drivers were apparently poor but free men, presumably the landless men described by Caesar. In the definitive conflict between the Romans and the Gauls in north Italy in 225-224 BC, the Celts employed 20,000 cavalry and chariots to the Romans' 70,000 horse.113 At the Battle of Telamon (225 BC) the chariots were positioned on the wings.

In Britain, as alluded to earlier, chariot warfare continued several centuries after such methods had become obsolete on the Continent. It was a vital part of the British battle-machine.114 The last reference to the use of war-chariots in Britain occurs in Dio Cassius's description of the Severan campaigns against the Caledonii of northern Scotland in AD 207.115

Julius Caesar's testimony on British chariot-warfare is detailed and informative. He ruefully remarks, 'thus they combine the mobility of cavalry with the staying-power of infantry.' He frequently comments that they used a combination of chariots and cavalry: 'they had sent on ahead their cavalry and the chariots, which they regularly use in battle.'116 Again, he mentions how the Britons ambushed the Romans while they were reaping grain, surrounding the legion with horses and chariots, and throwing them into confusion.117 On one occasion118 cavalry and chariots were used together in order to block the progress of the Roman army at a river. The Britons had a trick of drawing the Roman cavalry away from the support of their legion and then jumping down from their vehicles to fight on foot, giving them an advantage over the enemy.119 In discussing the Catuvellaunian king, Cassivellaunus, Caesar's most formidable British opponent, the Roman general describes the native chieftain's 4,000 chariots. Whenever the Roman cavalry went into the fields for grain, Cassivellaunus sent his charioteers out of the woods, where they had been concealed, and attacked them.120

Caesar's detailed account of the Britons' charioteering skills deserves to be quoted in full:

At first they ride along the whole line and hurl javelins; the terror inspired by the horses and the noise of the wheels generally throw the enemy ranks into confusion. Then when they have worked their way between the lines of their own cavalry, they jump down from the chariots and fight on foot. Meanwhile, the drivers withdraw a little from the field and place the chariots so that their masters, if hard-pressed by the enemy, have an easy retreat to their ranks. . . . Their daily training and practice have made them so expert that they can control their horses at full gallop on a steep incline and then check and turn them in a moment. They can run along the chariot-pole, stand on the yoke and return again into the chariot as quick as lightning.121

The chariot in war thus combined several functions. Battles involving chariots would have been formal engagements on selected ground.122 Conflict was highly ritualized, beginning, as Caesar describes, with insults, boastful riding up and down, clashing of weapons, challenges to single combat and only then a full-scale battle-charge. This all involved a great deal of social interaction and display.123 In a pitched battle, a great deal of chariot warfare was psychological: especially to an enemy unfamiliar with such tactics, the noise and speed of the horses and their rumbling vehicles driven full-tilt, the rain of the javelins, all combined to cause panic. The first line of the enemy was especially vulnerable to being trampled beneath the horses' hooves.

Chariots in early Ireland: the vernacular literature

Some of the earliest Insular literary records, which may well pertain to pagan Celtic traditions, contain fascinating allusions both to chariots themselves and to chariot warfare. The 'Tochmarc Emer', the story of the Ulster hero Cu Chulainn's wife Emer, describes a fine chariot built of wicker and wood, on white bronze wheels, with a gold yoke, a silver pole and yellow plaited reins.124 In the most famous of Ulster tales, the 'Tain Bo Cuailnge', both Queen Medb of Connacht and her bitter adversary Cu Chulainn possess chariots. Medb instructs her charioteer to yoke up her chariots ready to make a circuit of her camp and survey her armies.125 The young Cu Chulainn, a superhuman, semi-divine hero, breaks twelve chariots before finally finding one - that of his king Conchobar of Ulster - to carry him.126 Just before his death, Cu Chulainn yokes up his chariot for his final confrontation with Medb: he has two chariot-horses, the Black of Saingliu and the Grey of Macha. The clairvoyante Grey cries tears of blood at the foreknowledge of his death.127

The 'Tain' is full of allusions to chariots and, interestingly, makes specific reference to the shrunk-on iron tyres which were an invention of Celtic Iron Age smiths.128 The following is a description of Laeg, Cu Chulainn's charioteer, his chariot and his horses:

The charioteer rose up then and donned his charioteer's warharness. The war-harness that he wore was: a skin-soft tunic of stitched deer's leather, light as a breath, kneaded supple and smooth not to hinder his free arm movements. He put on over this his feathery outer mantle, made (some say) by Simon Magus for Darius king of the Romans. . . . Then the charioteer set down on his shoulders his plated, four-pointed, crested battle-cap, rich in colour and shape; it suited him well and was no burden. To set him apart from his master, he placed the charioteer's sign on his brow with his hand: a circle of deep yellow like a single red-gold strip of burning gold shaped on an anvil's edge. He took the long horse-spancel and the ornamental goad in his right hand. In his left hand he grasped the steed-ruling reins that give the charioteer control. Then he threw the decorated iron armour-plate over the horses, covering them from head to foot with spears and spit-points, blades and barbs. Every inch of the chariot bristled. Every angle and corner, front and rear, was a tearing place.

The body of the chariot was spare and slight and erect, fitted for the feats of a champion, with space for a lordly warrior's eight weapons, speedy as the wind or as a swallow or deer darting over the level plain. The chariot was settled down on two fast steeds, wild and wicked, neat-headed and narrow-bodied, with slender quarters and roan breast, firm in hoof and harness - a notable sight in the trim chariot-shafts. One horse was lithe and swift-leaping, high-arched and powerful, long-bodied and with great hooves. The other flowingmaned and shining, slight and slender in hoof and heel.129

World History

World History