Neolithic A period in the development of human technology that is traditionally the last part of the Stone Age. herders Workers who live a semi-nomadic life, caring for various domestic animals, especially in places where these animals wander unfenced pasture lands. cultigens Organisms, particularly cultivated plants, that do not have a wild or uncultivated counterpart. These are species that were domesticated (grown and selected by humankind) from so far back in antiquity, and have undergone such drastic transformation under prehistoric human selection, that the plant ancestry is essentially unknown.

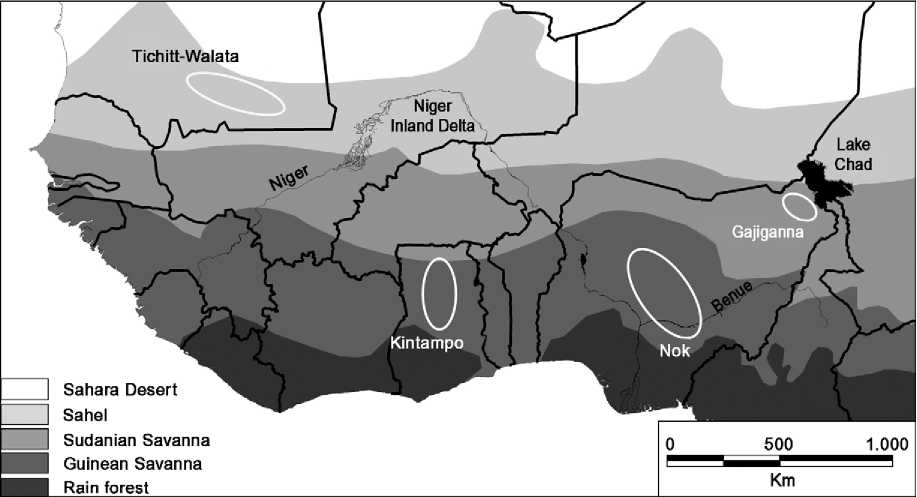

West Africa is bounded on the north by the Sahara, on the east by Lake Chad, on the south by the Gulf of Guinea, and on the west by the Atlantic Ocean. Distinctive vegetation zones running in an east-west direction are the result of decreasing precipitation from the Gulf of Guinea to the Sahara in the north. Between the tropical rain forest along the southern coastline and the Sahara Desert, the vegetation changes from Guinean to Sudanian to Sahelian savanna. This relatively close proximity of rather different environments and their considerable shift during the last millennia most likely influenced the appearance and development of herders and farmers in West Africa. During early Holocene times, vast areas of the Sahara resembled today’s Sahelian vegetation zone. It is in this region that important cultural innovations like the manufacture of pottery and the development of pastoral economy took place. Whether pastoral beginnings go back to the eighth millennium BC, as presumed on the basis of finds from the eastern Sahara, has been questioned. However, its existence in the central and eastern Sahara during the fifth millennium BC is beyond dispute. At this time, domesticated cattle appeared along with ovica-prids. While cattle might have been domesticated autochthonous, domesticated ovicaprids (sheep and goat) are believed to come from the Near East, because the fossil record and modern biogeography both indicate that their wild progenitors never lived in Africa.

After a flourishing period, the Saharan livestock herders were affected by the final desiccation of the Sahara caused by the southward shift of the Intertropical Convergence Zone. As a consequence, herders migrated into the moister southern regions. Archaeological data indicate that they started expanding into West Africa at around 2000 BC. Formerly existing disease barriers like the tsetse belt also shifted further south so that the vast grasslands in West Africa became suitable for pastoral occupation. The migration from the Sahara to West Africa is conclusive for several reasons. First, the dates for the earliest evidence of cattle get younger the more southerly the sites are located. Then, since the earliest domesticated animals have no local counterparts in sub-Saharan Africa, they must have been imported to West Africa. Finally, in some cases, the cultural material from the Sahara and the new homeland further south show similarities. How far farming and the beginning of plant cultivation were part of these migrations is one of the most important questions of sub-Saharan archaeology. With regard to the location of the wild progenitors of the African cultigens and theoretical considerations on the cultural context of initial farming, the southern Sahara is seen as the key area where the most important food crops of sub-Saharan Africa, pearl millet and sorghum, were originally cultivated.

Like anywhere else on earth, the appearance of herders and farmers with their food-producing economy constitutes a fundamental break in the prehistory of West Africa. Its occurrence is considered the prelude to a new era classified as the ‘West African Neolithic’. Herders and farmers are represented differently in the archaeological record. While the pastoral activities of herders are generally less visible, farmers and their sedentary communities usually produce abundant archaeological remains.

Contrary to other Neolithic centers in the world, for instance, the Near East, the African evidence indicates a considerable time gap between the appearance of herders and farmers. However, this ‘cattle before crops’ pattern is not very pronounced in West Africa. Here, in most cases, domesticated animals and plants (see Animal Domestication; Plant Domestication) appear almost simultaneously or with only a slight time difference.

The early food-producing communities must have met favorable conditions in West Africa, because both herding and farming activities spread very rapidly in manifold ways. One of the areas where comparably intensive research on early herders and farmers has been carried out is the Tichitt-Walata escarpment in Mauritania (Figure 1). The dry-stone architecture and the considerable size of the villages along the escarpment are unique among contemporaneous settlements in West Africa. Not only is it the northernmost food-producing complex in West Africa, but recent investigations have also shown that the area is among the earliest evidence of farming activities, dated to about 1800 BC. Another example for an early agropastoral society is the Kintampo culture in Ghana, located in the forest fringe and woodland savanna zones. The Kintampo people settled in rock shelters or hamlets consisting of huts spread over areas of up to 2 ha. They possessed domesticated animals, in particular sheep/goat and probably cattle, and cultivated pearl millet. In addition, there is evidence for the exploitation of the oil palm and a range of wild resources typical for the environment of the forest fringe and woodland savanna. Whether Kintampo emerged as a result of Saharan migration or represents a case of local intensification is discussed controversially. The floodplains and margins of the Inland Niger Delta constitute another focal point of agropastoral origins in West Africa. This region was home to a variety of cultural groups with different economic adaptations, appearing in the archaeological record during the second and early first millennium BC. One group is known as the Kobadi Neolithic of specialized fishers without domestic livestock or cultigens. Other groups have

Figure 1 West Africa: geographic zones and archaeological areas mentioned in the text.

Pastoral components, for example, Ndondi Tossokel, which originated from the Tichitt tradition in Mauritania or Winde Koroji. Early food-producing groups can also be found in the Sahelian zone of the Chad Basin in northeast Nigeria. Mobile herders arrived here in the early second millennium BC and became sedentary farmers or agropastoralists as documented by numerous village-like settlements dating from about 1500 BC onwards. In addition to such key areas of early food production, there are regions of marginal significance, where traces of herding cannot be detected by archaeological means or only appeared after the farming economy had established.

After a period of prospering development in the second millennium BC, the early herders and farmers apparently were faced with a crisis in the first millennium BC, probably stimulated by another severe drought. In many regions, cultural sequences faded away and gave way to completely new developments. Among the economic innovations of the first millennium BC were new cultigens. While pearl millet was the only cultivated plant before, other important crops such as sorghum, African rice, cowpea, bamba-ra groundnut, and okra as well as agro-forestry activities appeared between 500 BC and AD 500. They formed the basis of a productive Iron Age subsistence system where food security was more predictable than before. During the same period, large settlements, partly fortified, and site-size hierarchies emerged, followed by the development of urban centers, social stratification, and inter-regional trade during the latter half of the first millennium AD.

As a concomitant phenomenon of increasing cultural complexity, craft specialization is supposed to have developed during the first millennium BC (see Craft Specialization). Different concepts of craft specialization are discussed. Some accordant aspects highlight that craft specialization requires an economy able to produce surplus commodities in order to support craftsmen. It also intensifies the inequality among the members of a community, and thus favors the development of rank or class systems. But apart from these theoretical considerations, it is important to identify the existence of craft specialization in the archaeological record. Craft specialization can appear at the household level, as a form of part-time specialization concerning objects of daily use such as pottery, bone tools, mats, and basketry. In West Africa, this form of specialization possibly originated among the early herders and farmers of the second millennium BC, or even earlier in a hunter-gatherer context. A more complex craft specialization beyond the household level appears to have developed only during the first millennium BC. From this period onwards, evidence for concentrations of manufacturing by-products in specific sections of settlements is found. Another important innovation of the first millennium BC is iron metallurgy. While its origin and spread in sub-Saharan Africa is a matter of a long-running debate, there is no doubt about its technological advancement and the demand for specialists to conduct iron smelting and processing. Together with early iron metallurgy, art appears as another impressive case of craft specialization. Undoubtedly, the earliest art of West Africa, the expressive terracottas of the Nok culture in central Nigeria, were created by specialists belonging to a stratified society and not by herders and farmers as a result of leisure activities.

As a conclusion, the first millennium BC was a period of crises, discontinuities, and innovations with paramount importance for subsequent times. Fundamental economic, technological, and social changes took place and were the basis for developments which led to the formation of civilizations and empires only a few centuries later.

See also: Animal Domestication; Craft Specialization; Plant Domestication.

World History

World History