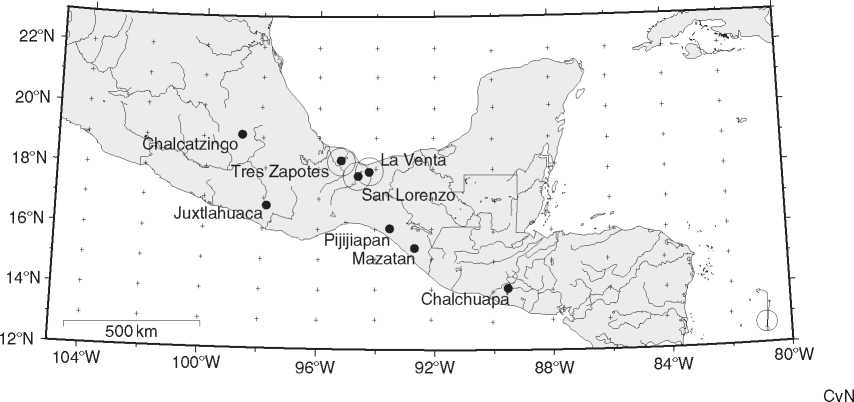

Scholars recognize that the Olmec were a key factor in the foundation of Mesoamerican culture, but there is disagreement about what the term Olmec refers to and who the Olmec were. Historically, the term Olmec has signified a particular art style, a constellation of cultural traits, the materialization of an emergent rituality associated with developing Mesoamerican political economies, and a regional archaeological culture that developed within the Gulf coastal lowlands of the Mexican state of Veracruz and adjacent Tabasco during the centuries between roughly 1500 and 400 BC (Figure 1). The first recognition of the distinctive complex of art associated with the archaeological Olmec is attributed to Jose Melgar who published an account of a colossal carved head at Tres Zapotes in 1871.

Olmec archaeology began in earnest with the work of Mathew Stirling. Stirling began in the Gulf Coast Olmec region in 1938 with the intention of investigating major sites, including Tres Zapotes in Veracruz. Later work at Tres Zapotes was undertaken by Christopher Pool. Philip Arnold and Susan Gillespie, among others, have worked at a variety of Early and Middle Formative Olmec sites within the Tuxtlas Mountains. San Lorenzo became the focus of an intensive project during the late 1960s under the direction of Yale University’s Michael Coe and Richard Diehl. Coe and Diehl were the first to develop a well-researched ceramic chronology tied to radiocarbon dates. Ann Cyphers and her coworkers undertook later work at San Lorenzo. Stacy Symmonds, Carl Wendt, and others have conducted systematic research in the Coatzacoalcos basin adjacent to San Lorenzo. The nearby ritual shrine site, El Manati, with its sequence of spring-focused caches of ceremonial celts and wooden busts, was excavated by Ponciano Ortiz Caballos and Ma. del Carmen Rodriguez.

Following Frans Blom’s initial visit to La Venta in Tabasco, Stirling excavated the site and was followed by Heizer, Drucker, and the Mexican archaeologist Pifia Chan. More recently, work at La Venta was renewed by Rebecca Gonziilez Lauck and coworkers. William Rust documented a network of settlement beyond the polity core, possibly similar in organization to that documented by Cyphers and colleagues around San Lorenzo. Work at several sites subsidiary to La Venta by archaeologists, including Mark Raab at Isla Alor and Mary Pohl and Kevin Pope at San

Figure 1 Map of the Olmec region within Mesoamerica showing important sites mentioned in the text. The three major Olmec sites, San Lorenzo, La Venta, and Tres Zapotes are shown with 50 km radius circles, approximations of possible zones of primary economic interaction. La Venta acquired resources, boulders and cobbles for grinding stones, larger stone for sculpture and architectural elements, and volcanic ash for pottery temper, from as far or further afield than the 50 km circle shown here. Both San Lorenzo and La Venta acquired raw materials for sculpture from the Tuxtla Mountains. Secondary and tertiary centers associated with each Olmec capital are well contained within these circles.

Andreis, has provided detailed ceramic, palynological, and subsistence history for the La Venta region. Further east, following initial work by Edward Sisson, Christopher von Nagy undertook a systematic survey of the Plan Chontalpa region documenting a network of ancient Olmec settlement along a series of ancient distributary channels. Significantly, these projects have provided robust palaeobotanical, zooarchaeological, and palynological data on subsistence systems. Historical linguists such as Terrence Kaufman have determined that speakers of the Mixe-Soke language group, specifically the Soke, are the probable descendents of the ancient Olmec.

World History

World History