Mounded Open Sites

Ur in southern Mesopotamia (southern Iraq). Because there is no stone in the Tigris-Euphrates floodplain of southern Mesopotamia, the communities built there thousands of years ago (and, in fact, well into the twentieth century AD) are constructed of sun-dried mud brick. When abandoned, mud brick buildings disintegrate into low heaps, which may be leveled and used as foundations for new structures, or may simply be left if occupation shifts to an adjacent area. Thus, archaeological remains of the ancient city of Ur are a series of mounds and undulating cultural deposits covering a large area (some 150 acres (60 ha)), and comprising collapsed remnants left by generations of private and public mud brick buildings marking the history of Ur from c. 5000 BC to the Islamic era (which began in the seventh century AD). Several Sumerian cities so far identified in southern Mesopotamia are larger than Ur - Nippur is estimated at 800 acres (320 ha), Uruk at 1100 acres (450 ha) - but Ur is better known in the Western world because it is mentioned in the Old Testament as the birthplace of Abraham. (See Asia, West: Mesopotamia, Sumer, and Akkad).

Tell al-Muqayyar, the modern name for the ruins of Ur, was first excavated in 1853-54 by the British vice-consul stationed in Basra, then again by other archaeologists for brief periods in 1918, but most of what is known derives from long-term work directed by Leonard Woolley from 1922 to 1934, funded by the British Museum and the University of Pennsylvania Museum. Woolley was an excellent field archaeologist by the standards of his day, and made headlines in Europe and the United States by his finds at Ur, especially those from what he called the Royal Tombs. Within what he identified as the Early Dynastic Sumerian Royal Cemetery (dating to approximately 2500 BC), he excavated 660 burials, 16 of which were of the ‘royal’ category. These tombs were quite elaborate architecturally, and a few contained multiple retainers (up to a total of 73 people in the largest one), as well as abundant grave goods, some made of precious exotic and imported metals (gold, silver, electrum) and gemstones (lapis lazuli).

Woolley’s workmen also uncovered the remains of numerous structures (walls, temples, administrative buildings, storerooms, private residences) and exposed the great Ur ziggurat (a massive, multiterraced temple platform that had risen more than 85 ft (26 m) high), which he reconstructed in the years before World War II.

Viking ship burials in Norway. As demonstrated by the Royal Tombs of Ur, and as is the case in many other societies, the Iron Age inhabitants of Scandinavia during the Viking Age (eighth-eleventh centuries AD) provided their elite dead with rich arrays of grave goods, covering the grave sites with low, round, or oval earthen mounds. Some of these burials also included large, well-built sea-going ships. Several such vessels have been excavated from the mounds that covered them, and have provided detailed information about when and how they were constructed. One of the best-preserved Viking ship burials is that from Oseberg on the shore of Oslo Fjord in Norway. Together with two other ships excavated elsewhere along Oslo Fjord, the Oseberg ship is on exhibit at the Viking Ship Museum in the city of Oslo.

Tree-ring dates obtained for all three ships indicate that Oseberg is the oldest, having been built c. AD 815-20, and buried (according to dates for the burial chamber housing the ship’s owner) in AD 834. The royal personage in the Oseberg mound was a woman (actually, fragmentary skeletal remains of two women were recovered from this tomb), accompanied by the richest array of goods and equipment ever found in a Viking tomb. Besides the ship, there were also, for example, seven sleds (three of them elaborately decorated), a wagon, 12 or more horses, four dogs, a peacock, silk and woolen tapestries, goatskin shoes, combs, pins, spindles, scissors, wooden buckets, a loom, and other domestic equipment including the remains of down-filled bedcovers.

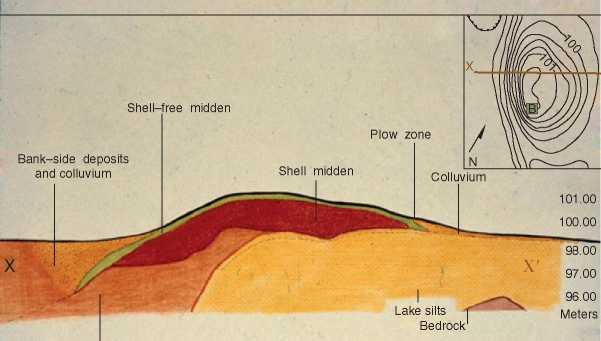

The Carlston Annis shell mound in Kentucky, USA. Shell mounds or shell middens comprise a site type found in many parts of the world where abundant molluskan resources were permanently present, and were collected and processed at seaside or riverside locales. Such middens date back at least as far as the Mesolithic and Neolithic periods in Europe and eastern Asia, and to the Archaic period in the Americas. They vary considerably in size, shape, and internal composition, but the Carlston Annis shell mound on the Green River in west-central Kentucky, USA, provides one good example (Figures 1-4).

The Carlston Annis site dates approximately 3000 to 2000 BC, and has been under cultivation for many decades. As a result, the surface contours are different from what they were prior to plowing, planting, and harvesting of corn (maize) beginning in the early twentieth century. The mound is now a long oval approximately 100 x 75 m (325 x 244 ft), but was formerly roughly circular and 80-85 m (65 x 84 1/2 feet) in diameter. The maximum depth of cultural deposit is somewhat more than 2 m, and contains varying amounts of mussel shell from the adjacent Green River, fragmented sandstone (used in hot-rock boiling and roasting) from the bluffs that

Figure 1 The Carlston Annis shell mound (15Bt5) near Logansport, Butler County, Kentucky, USA (photo by William Marquardt, Shell Mound Archaeological Project).

Bank-side deposits pre-midden

Figure 2 Geoarchaeological profile of the Carlston Annis shell mound (15Bt5), Kentucky, USA (figure provided by Julie Stein, Shell Mound Archaeological Project).

Meters

Cross-section of 15 Bt 5

Outcrop a mile or so back from the river, hundreds of human burials as well as many dog burials, broken animal bones (fragmentary remains of wild fauna such as deer, turkey, fish, turtles, etc., hunted and eaten prehistorically), charred plant remains, and numerous stone and bone artifacts.

Because the shell mound is rich organically, and is located in a region with high rainfall, relatively mild winters, and hot humid summers, the ancient deposits are inhabited by many different kinds of burrowing creatures from earthworms and other insects to crayfish, snakes, mice, gophers, and groundhogs. Hence, documenting human cultural remains and activities requires careful attention to what is known as bioturbation (see section titled ‘Methods’ ahead).

Unmounded Open Sites

Head-Smashed-In, Alberta, Canada. In many places around the world, locales where one or more wild animals were killed and butchered have been preserved. Some such unmounded sites represent a single episode when one or two mammoths or mastodons, for example, were brought down by skillful and daring human hunters, or were killed after being injured or impaired in some manner. Another type of kill-site contains the remains of multiple drives whereby dozens of herd animals (e. g., bison, wild horses, and gazelle) were stampeded over cliffs or into natural or artificial enclosures and killed. One such site of the latter type (known in North America as a ‘jump site’)

Figure 3 Close-up view of cultural deposits at the Carlston Annis shell mound during excavation. Marks on the North arrow are 1 cm wide (photo by William Marquardt, Shell Mound Archaeological Project).

Figure 4 View of Carlston Annis shell mound after the surrounding agricultural field had been plowed. Note contrast between the dark mound deposit and the lighter soil of the field. Tree line beyond the mound marks the course of Green River (photo by William Marquardt, Shell Mound Archaeological Project).

Is Head-Smashed-In near Fort MacLeod in western Canada within the province of Alberta. Beginning in the Archaic period more than 5000 years ago and continuing into the nineteenth century, American Indians, cooperating in autumn hunts, drove groups of bison over a low cliff killing them, or severely injuring them so that they could be easily dispatched. Most of the resulting meat would have been sun-dried or smoked and kept for use throughout the winter.

The copper mines of Isle Royale in Lake Superior, Minnesota, USA. Surface mines are yet another type of unmounded open site, and are known from many parts of the world where valuable natural resources or raw materials such as flint and salt, precious stones such as turquoise, and metals such as copper were quarried to be used locally as well as exported. By 7000 years ago, Archaic people in the Lake Superior region of northeastern North America were obtaining native copper, probably from both open (stream-deposited, or exposed by stream erosion) and embedded deposits. Later pre-Columbian inhabitants of the Great Lakes area intensively mined rich copper veins on Isle Royale near the northern shore of Lake Superior itself. Hundreds of pits and trenches (some up to 3 m (10 ft) deep) dug c. 6000-1500 years ago by Late Archaic and Early to Middle Woodland miners as they followed copper seams, are still visible on Isle Royale as are large quantities of the hammerstones used to remove workable copper nodules and chunks. Occupation sites containing fragments of worked copper are also known on Isle Royale, and there is some evidence from as far south as Alabama, Florida, and Georgia that Lake Superior copper was widely traded prehistorically.

The Little Bighorn Battlefield, Montana, USA. A third example of unmounded open sites, one that is widely distributed in time and space, is that of the battlefield. Battlefields are known both archivally and archaeologically from as long ago as the Bronze and Iron Ages in Europe and the Mediterranean regions, but the most detailed investigations are currently being carried out on historic sites dating to the last few centuries or decades (e. g., Civil War battlefields (1860-65) in eastern North America, US ships sunk by the Japanese in 1941 at Pearl Harbor, Hawaii).

Detailed archaeological and osteological investigation was begun recently and is continuing at the Little Bighorn Battlefield in eastern Montana. Here, on 25 June 1876, Sioux chieftains, warriors, and their allies wiped out the US Seventh Cavalry, commanded by General George A Custer. Fieldwork carried out at the Little Bighorn site (now preserved as a National Monument) between 1985 and 1989 yielded detailed documentation on bullets, cartridge cases, textile fragments, Sioux and Cheyenne artifacts, and some osteological remains of Seventh Cavalry troopers. Laboratory work included distributional analyses of the artifacts recovered, especially the bullets and cartridge cases, to produce detailed information on specific locations of cavalrymen and Indians during the battle.

World History

World History