In the Sioux tradition, Wakan Tanka is “The Great Spirit” that resides in every thing. Every creature and object has a wakan, such as wakan tanka kin, the wakan of the sun. The connection between the spirit world and the human took place in the context of large ceremonial dances staged during various parts of the year. The spirit-walkers (or powwaw [“spiritual leader”] in the Narragansett language) helped guide the process. This takes its most architectural form with the sweat bath, a ritual that extends across numerous cultures from the Saami in Finland to the Alaskan Eskimo all the way to the land of the Mayans.36 Its roots are ancient. Herodotus, the Greek historian living the fifth century bce, describes Scythian funeral rites in which tribe members set up a cone-shaped structure, cover it tightly with felt, and throw hemp seed on the fire within to produce a vapor bath.37 He notes that during the process, “they howl with pleasure,” no doubt because hemp is related to cannabis. The purpose of the ritual went far beyond getting the body clean. It lay at the core of clan and tribal identity. Archeological evidence is difficult to come by since sweat lodges can be easily mistaken for huts. Furthermore, since all huts had ritualistic components, any hut could potentially have been used for such ritual purposes. The most important source of information about sweat lodges comes from the Native Americans, for whom in some parts it is still a living tradition.

For the Nez Perce in Idaho, the sweat bath could be simply an outdoor, natural pool next to a stream with a fire nearby to heat the rocks. But mostly, lodges were constructed as a hut, between 7 and 8 feet in diameter. A hole about 2 feet in diameter and approximately 1 foot deep was dug out of the soil just inside and to one side of the door. This served as a container for the heated stones. The fireplace was usually on a slight elevation within 10 to 15 feet of the sweat house and to its east. This elevation facilitated the rolling of the hot stones from the fireplace into the sweat house. Once the stones were inside and arranged in the pit, water was put on them to create steam. Between the entrance to the lodge and the sacred fire there was usually a conceptual barrier beyond which none might pass except the fire keepers. Traditionally this sacred barrier consisted of a buffalo skull atop a post. The participants placed items sacred to their clan or group—such as sage, sweetgrass, or feathers—at the base of the altar.

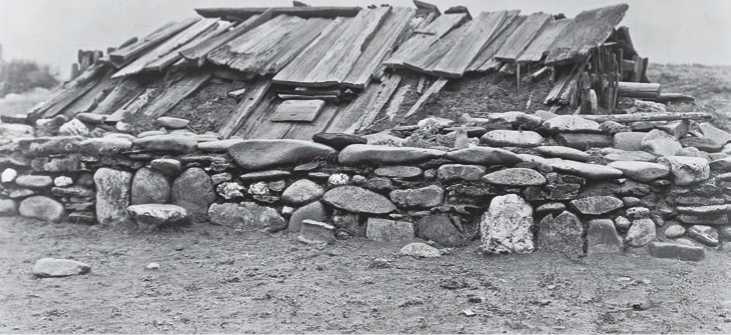

Figure 4.34: Hupa Sweat House, California, USA, 1923. Source: Edward Curtis Collection, Prints & Photographs Division, Library of Congress, LC-USZ62-120023

Figure 4.35: Sweet lodge frames, North Dakota, USA. Source: Rachel Schmitz

Most lodges were built as a frame of bent poles covered with hides or bark shingles, but the shape varied depending on materials and local traditions (Figures 4.34 and 4.35). Some were circular or oblong, whereas others consisted of a pit or trench dug into the ground and covered with planks, furs, sod, or tree trunks. The building of the lodge was, however, always a sacred act. Some were made in complete silence, while others involved singing, chanting, or drumming.

Once the lodge was activated, the stones were no longer material objects, but the embodiment of the Stone People spirits awakened by the heat; the steam rising from the stones became their voices and embodiment. During the ceremony, which is guided by the sweat lodge leader, the stones might be moved to different locations, accompanied by songs and chants. A ceremony was typically four sessions, each lasting about thirty to forty minutes. In some cultures a sweat lodge ceremony was part of other, longer ceremonies, such as a Sun Dance. In almost all cases, the ceremony was done in complete darkness. Various types of plant medicines were often used to tender prayers, give thanks, or make other offerings. In many traditions, one or more persons will remain outside the lodge to protect the ceremony, and assist the participants and tend the fire.

Although they served a variety of purposes, the lodges were particularly important to the social identity of the group. For example, whenever a visitor came to a village, he always sought out the sweat bath and made his contacts there under the obligatory friendly conditions. It was considered an insult to refuse an invitation to a sweat house ceremony. The sweat house was also used after periods of physical exertion, such as after a hunt or a war, and was believed to produce sound bodies and steady nerves. Occasionally the women used the same sweat bath as the men, merely at a different time of day, but the perceived danger of menstrual pollution often meant separate structures.38

World History

World History