The uplift of the Himalayan mountains, along Qinghai-Tibet Plateau, and appearance of Eurasian steppe deserts had a unique and significant impact on the palaeoenvironment on East Asia. These environmental changes inhibited the direct interaction of

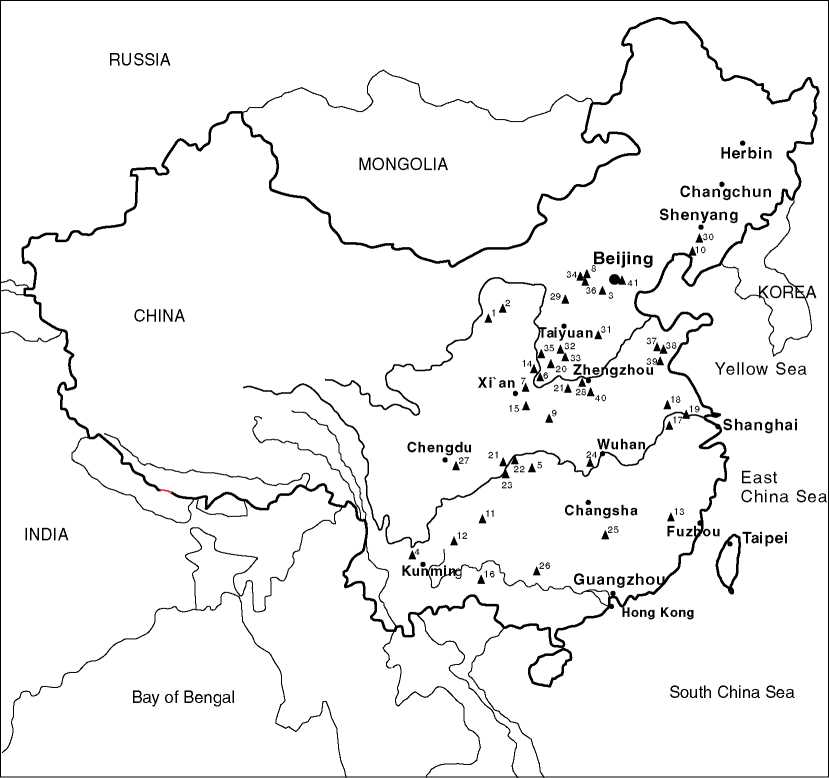

Figure 1 Major Palaeolithic sites in China. 1, Shuidonggou; 2, Sjara-osso-gol (Ordos); 3, Zhoukoudian (Locality 1, Locality 15, the Upper Cave, Tianyuandong); 4, Yuanmou; 5, Longgupo; 6, Xihoudu; 7, Lantian; 8, Nihewan (Goudi, Majuangou; Donggutuo, Xiaochangliang, Banshan, Cenjiawan, Maliang, Youfang); 9, Quyuanhekou; 10, Jinliushan; 11, Guanyindong; 12, Dadong; 13, Sanming Lingfengdong; 14, Dali; 15, Luonan (Longyadong); 16, Baise; 17, Maozhushan; 18, Hexian; 19, Tangshan; 20, Dingcun; 21, Ranjialukou; 22, Gaojiazheng; 23, Jingshuiwan; 24, Jigongshan; 25, Maba; 26, Liujiang; 27, Ziyang; 28, Zhijidong; 29, Shiyu; 30, Xianrendong; 31, Xiaonanhai; 32, Xiachuan; 33, Xueguan; 34, Hutouliang; 35, Shizitan; 36, Jiqitan; 37, Qingfengling; 38, Fenghuangling; 39, Wanghailou; 40, Lingjing; 41, Dongfang Plaza.

Hominids on both sides of the Old World. Nevertheless, these geological and environmental barriers did not prevent early African hominids from entering East Asia as early as 1.7-1.6 million years ago. The earliest occupations were distributed in the central China between 25° and 40° N latitude. During the Lower Pleistocene (1.8-0.78 million years ago), the palaeoenvironment in central-northern China was much warmer and moister than today, similar to the subtropical climate that comprised early hominids’ living habitats. Most of these earliest hominid settlements were found in open-air sites near water sources in what is today a hilly environmental setting. The lithic technology of these early hominids in the new

Land was noticeably different from their counterparts in the West.

Geological tectonic movements and temperature fluctuations during the Middle Pleistocene started to create a geological boundary through what are today the Qinling Mountains. Northern China became drier and colder, resulting in temperate-prairie zones, while southern China retained the same subtropical climate as before. By this time, Asian hominids seemed well adapted to different environments, and Early Palaeolithic sites have been found almost everywhere across the vast landscape of China. Their decision to locate in cave sites and open-air sites was probably based on survival strategies. During this time, there is evidence for intentional use of fires, and the formation of two different technologies (flake-tool industries in the North and pebble-core tool industries in the South) occurred.

During the late Middle Pleistocene to early Upper Pleistocene, Mousterian industries (represented by Neanderthal cultural remains) dominated the western side of the Old World, but had little impact on cultural changes in China. Here, the cultural remains of the early Upper Pleistocene show a continuous development from its preceding cultures. Thus, the term ‘Middle Palaeolithic,’ once used to identify Palaeolithic sites dated to this period, now seems irrelevant when discussing lithic industries that have little difference from the early period. For the purpose of comparison, however, our summary of these sites will still be under a separate heading, but designated as late Early Palaeolithic.

The most significant environmental event that occurred during the Upper Pleistocene was the climate change from the Last Inter-Glacial to the Last Glacial period. The climatic influence was once again greater in North China than in South China, and as a result, the northern flake-tool industries were pushed southward, replacing the pebble-core tool industries in Middle-Lower Valley of Yangtze (Changjiang) River. This transition, or cultural interaction between the North and the South, was evinced by the Palaeolithic remains recovered in recent investigations in the Three Gorges area.

Another environmental change was the quick accumulation of Malan Loess across northern China, which resulted in the northern lithic industries being more adaptive to loess environments. The Malan Loess is the best chronological indicator, and provides Palaeolithic researchers with an opportunity to examine the human behavioral changes of the late Early Palaeolithic in response to environmental changes, although such studies in China are still in its infancy.

By 40 000-35 000 BP dramatic cultural changes occurred in China, evinced by the sudden appearances of blade technology, bifacial technology, and especially microblade technology. These new technologies mixed with the indigenous lithic industries, thereby forming unique Late Palaeolithic cultures. These cultural changes were directly related to the migration and subsequent spread of anatomical modern humans in China. Whether or not modern humans also originated independently in East Asia is still open to debate; nevertheless, the spread of modern humans from the West via the vast Eurasian Steppe and Eastern Siberia undoubtedly contributed to the complexity and variability of Late Palaeolithic lithic industries. Clearly, China, especially northeastern China, at the end of Pleistocene was part of a cultural intersphere that eventually reached the New World during 20 000-11 500 BP.

World History

World History