A rather different Neolithic tradition is documented from Kashmir and the far north of Pakistan (the Swat Valley), although it appears to have derived its crops from the same suite of winter crops of Near Eastern origins. Generally known as the Northern Neolithic, this tradition is best represented by sites in the Kashmir Valley, although related sites can be identified in Swat (Northwest Pakistan). Here sites occupy the milder valley bottoms and began to be occupied between 3000 and 2500 BC, represented by the sites of Burzahom, Gufkral, and Ghaleghay, but with more evidence and sites dating closer to 2000 BC. The earliest phases are characterized by broad deep pits, with bell-shaped profiles, and lack pottery. While these have conventionally been interpreted as pit houses, recent debates have raised the likelihood that they were large storage features. Whatever the case, it is clear from these sites that the dominant crops were winter wheat, barley, peas, and lentils. It is possible that these crops had diffused to local hunter-gatherers from the Indus region to the south or from Central Asia, together with domesticated animals. Impressions in pottery from Ghalegay suggest some localized rice cultivation as well which must have diffused from the Gangetic region to the southeast.

The West: Hunter-Herders to Millet Farmers and Traders

The areas to the south and east of the Thar Desert, the Indian states of Gujarat and Rajasthan, are likely to have been regions both of the extension of the winter-crop agriculture and livestock from Baluchistan as well as local traditions of cultivation based on indigenous domestication. Gujarat is likely to have been a center for the domestication of local, monsoon-adapted crops, perhaps after livestock was adopted into this area from the Indus region to the west in the fourth millennium BC. Archaeobotanical evidence for the beginnings of cultivation in this region is not yet available from the earliest ceramic-bearing sites, of the Padri and Anarta traditions (c. 3500-2600 BC), but the extensive sampling on Harappan period sites in the region after 2600 BC indicates the predominance of small millets, in particular, little millet (Pani-cum sumatrense) but probably also Setaria spp. and Brachiaria ramosa. Nevertheless, these sites and contemporary sites further north on the Thar Desert fringes of northern Gujarat and Rajasthan have produced evidence for some domestic fauna in the earliest ceramic levels, including cattle bones from the mid-fourth millennium BC at Loteshwar and probable domestic fauna from Padri. Other sites, such as Bagor, are often cited as evidence for the adoption of livestock by mid-Holocene hunter-gatherers, although current knowledge highlights the need for more systematic archaeobotanical and archaeozoological investigations.

East of the Thar Desert there is clear evidence for establishment of agricultural villages before the end of the fourth millennium BC. Demonstrated by excavations at the site of Balathal, more or less sedentary ceramic-producing farmers became established in this region alongside hunter-gatherers such as those of Bagor. Limited archaeobotanical data suggest that Balathal agriculture was based on the winter crops from further west, together with livestock, rather than indigenous crops. These crops were then taken up further east in central India and on the northern Peninsula in the second half of the third millennium BC. On the northern peninsula the winter cereals and pulses were markedly important but they seem to have been part of a mixed cultivation strategy which included significant frequencies of the native species, such as the pulses and millets that featured prominently in the Southern Neolithic.

The North and East: Potting Foragers to Rice-Growing Villagers

The Ganges Basin, the adjacent Himilayan foothills to the north, and the hill zones of Bihar and Orissa taken together delimit an important zone of probable plant domestications. Evidence has long been clear that a number of cucurbit crops originate in this general area, including cucumbers, luffas and various ‘gourds’, although only the ivy gourd has an archaeological record. Of special interest is, of course, the predominant staple today, rice, which is also native domesticate of this region. Rice is consistently present at all these sites from the earliest documented phases together with various small millets (B. ramosa, Setaria vertcillata, and Setaria pumila). Native Indian pulses are also present but only from later phases, which could indicate dispersal of native pulses from elsewhere prior to 2000 BC. Still to be clarified is whether there was one main trajectory toward agriculture or dispersed parallel trajectories in different local traditions, and what role interactions between early farmers and hunter-gatherers played.

At present three distinct cultural traditions can be defined, each of which passed through two or three economic stages. First there is a tradition located in the eastern part of this region, represented by Lahuradewa and Senuwar. Its earliest stage, represented by occupation of the lake margin area at Lahuradewa, shows ceramic production by sometime in the fifth millennium (and perhaps as early as 7000 BC), and rice was part of the diet from 7000 BC, although clarification is needed on its cultivation status and the earliest rice material is plausibly wild. Later levels at Lahuradewa and at Senuwar indicate more sedentary settlement and clear rice cultivation after 2500 BC. Some winter crops, especially wheat and barley, were added to the agricultural system by 2200 BC, and pulses from elsewhere in India were

Added shortly thereafter. Livestock were also adopted, beginning perhaps as early as 2500 BC and certainly by c. 2000 BC. A second tradition that shows parallel economic developments was in the northern Vindhyan hills and the Son and Belan river valleys, represented by sites such as Mahagara, Koldihwa, and Tokwa, although here the founding of sedentary villages with mixed agro-pastoralism occurred mainly after c. 2000 BC (Figure 7). Once again the initial agriculture was rice and millets, with winter crops and pulses adopted shortly thereafter. Earlier evidence in the region suggests seasonal settlement, rice use, and probably some production of ceramics among hunter-gatherers. A third distinct cultural tradition to take up agriculture was the Mesolithic of the central Ganges plains, represented by the site of Damdama. Here there has been a long tradition of semisedentary hunting and fishing focused on the oxbow ponds and former meanders of the Ganges plain. Despite the absence of pottery, crops, including rice and barley, were adopted after 2500 BC, but this distinct aceramic tradition ceased to be recognizable by the early second millennium BC.

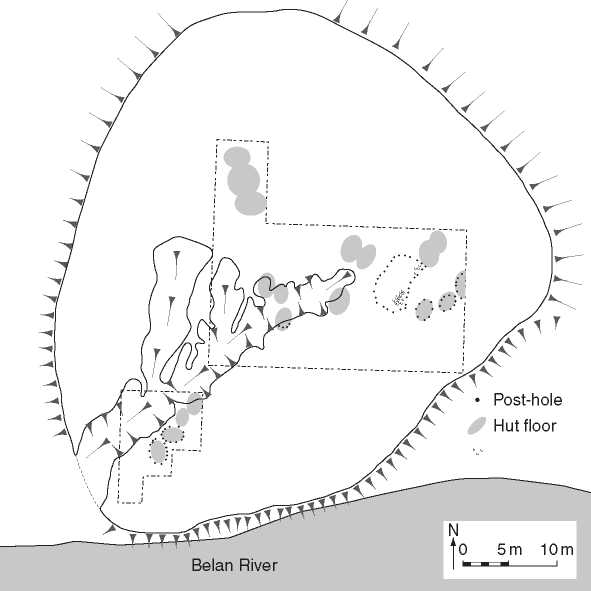

After 2000 BC agricultural villages became more widespread in the Gangetic region. They seem to have consisted of small villages of round huts and possible communal animal pens (Figure 5). While it is not yet clear that these sites were truly year-round sedentism, it is clear that they were much more permanent and long-lasting than anything that had been before. It is also clear that cultivation was established before this phase of sedentarization. Indeed, finds of probable Gangetic domestics in the Eastern Harappan zone suggest that the beginnings of cultivation date to before 3000 BC. The recent discovery of Lahuradewa dating back to before 4000 BC suggests that future work may indeed be able to elucidate the plant economies of less settled societies that saw through the transition from foraging to food production.

During the course of the second millennium BC, agriculture diversified as did other aspects of the society. It is during this period that the first evidence for aboriculture of native tropical trees occurs. This includes evidence from wood charcoal suggesting the planting of trees in the Gangetic Plains such as jack-fruit (Artocarpus heterophyllus), mango (Mangifera indica), bael fruit (Aegle marmelos), the citron (Citrus medica), and tamarind (Tamarindus indicus). Fruit-tree cultivation may have begun early in the second millennium BC but was widespread by the second half of the millennium. It is also during this period that the first finds of possible fiber crops, including flax and hemp, occur, together with probable spindle whorls, suggesting the beginnings of textile production.

The Lesser Known East and Northeast: Orissa, Assam, Bangladesh and Burma

Areas in Eastern India and the far northeast, including Bangladesh and Myanmar (Burma), are still poorly explored in terms of Neolithic archaeology. In the past few years a few Neolithic sites in lowland Orissa have been studied. In the lowlands of Orissa, along the coastal plain and the Mahanadi River substantial archaeological settlement mounds exist. This provides evidence for Neolithic settlement based on the cultivation of rice and Indian pulses as well as herding of domesticated livestock, including introduced sheep and goat. Rice, some of the pulses, and water buffalos are all candidates for domestication in this region, although there is not yet clear archaeological evidence documenting this. While some of these sites, such as Golabai Sassan, may have been founded before

Figure 4 View north across the Belan river from Koldhiwa Neolithic site to Mahagara (on left), Uttar Pradesh, 2001.

Cattle hoof-prints

Figure 5 Plan of the Gangetic Neolithic settlement of Mahagara, c. 1700 BC, indicating the distribution of huts in relation to a small animal pen.

2000 BC, most of the substantial occupation seems to start later closer to 1500 BC and continue perhaps a thousand years into the Iron Age (Figures 6). In the upland regions of Orissa the Neolithic is known mainly from surface collections of ground stone axes, although ceramics from the site Kuchai, which are tempered with rice husk, suggest some rice cultivation. Possible precursors to the Neolithic settlements may be sought in the many rock shelters of northwest Orissa, which are rich in rock art, and sometimes include ceramics in their surface collections.

Similarly, in the northeastern states of India, such as Assam, and neighbording Myanmar, the Neolithic is known only from surface collections of ground-stone axes and ceramics. The Neolithic remains unidentified in Bangladesh. There is not yet any clear evidence for dating the Neolithic in these areas, nor for inferring the economic basis. Scholars have long noted that in this zone shouldered axes are typical, and that this tool type suggests possible links with Orissa and parts of Southern China. While this typological linkage has featured in several models of Neolithic population dispersal, it remains undocumented through excavated archaeological contexts.

The South: Millet and Pulse Farming Cattle Keepers

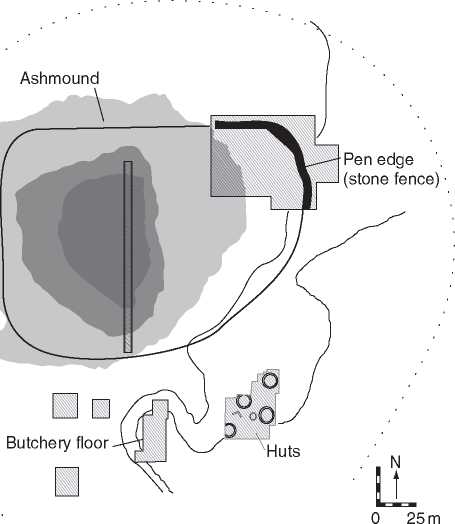

The Southern Neolithic, of northern Karnataka and southwest Andhra Pradesh, provides the earliest evidence for pastoralism and agriculture in Peninsular India, starting by 2800 BC. A well-known site category of the Southern Neolithic is the ashmound (Figures 7, 8, and 9). These sites form a prominent part of the archaelogical landscape of Southern India and consist of large accumulations of burnt cattle-dung reduced to ash and in some cases to a slag-like consistency. Excavations, especially at Utnur and Budihal, have revealed these to be ancient penning sites that have been episodically burnt, probably as part of seasonal communal rituals. The centrality of cattle in this symbolic aspect of life is also suggestsed by a rich rock art corpus associated with some Neolithic sites in the region, which are dominated by pecked images of cattle. While these sites were seasonal encampments, in many cases they developed over time into village settlements. This is indicated by ashmound deposits buried under village occupation at sites such as Sanganakallu (Figure 10), and by the development of a village adjacent to the ashmound at Budihal (Figure 11). These transitions are part of a protracted regional process of increasing sedentism between 2200 and 1800 BC. After 1800 BC the distribution of ashmound sites had reached their maximal extent in northwestern Karnataka, and other traditions of village settlement began to be established in adjacent regions, of West and South Karnataka, Andhra Pradesh, and northwest Tamil Nadu. Agriculture further South, throughout

Figure 6 The Neolithic/Chalcolithic settlement mound at Golabai Sassan, Orissa. The site is cut through by the road, 2003.

Figure 7 Kudatini, the largest Neolithic ashmound, west of Bellary, Karnataka, 1998.

Tamil Nadu for example, appears to have only become established during the Iron Age and in some regions of Southwest Tamil Nadu as late at the end of the first millennium BC. Here agriculture included rice, which had diffused from northern India, perhaps along the eastern coast early in the first millennium BC. Similarly, rice-based agriculture came to Sri Lanka, perhaps by c. 900 BC. This long regional transition from hunter-gatherer societies to agriculturalists is also characteristic of the hill tracts of peninsular India, where in some areas hunter-gatherers became specialized forager-traders tied to agricultural societies in the plains, and some of these forager-trader

Communities persisted into the ethnographic present. The subsistence of the Southern Neolithic combined indigenous crops with introduced livestock. Animal bones indicate the dominance of cattle in the animal economy with a smaller presence of sheep and goat. While the latter species must have been adopted from the north, this also seems likely for the cattle. Recent archaeobotanical research has provided a picture of recurrent staples and occasional secondary crops of the Southern Neolithic. The staples include two native species of millets (B. ramosa and Setaria verticillata) and two pulses, mungbean and horsegram (Vigna radiata and Macrotyloma uniflorum). The existing

Figure 8 The Southern Neolithic ashmound site of Palavoy, showing exposed stratigraphy of durg ash layering, Anatapur District, Andhra Pradesh, 1998.

Figure 9 Two ashmounds at Palavoy seen from above, looking West, the ashmound at right is shown close-up in Figure 8.

Evidence indicates dependence on a group of species that are native to the peninsula, with non-native species being rare (on a minority of sites) or occurring only in the latest Neolithic period, including crops of African origin by c. 1500 BC. In addition, evidence from this later phase of the Neolithic suggests the adoption of fiber crops, cotton and flax, as well as some fruit trees such as mango and citrus. In all, this indicates increasing diversity and links between agriculture, craft production, and trade.

Concluding Remarks: Directions in South Asian Neolithic Research

Throughout most of India, the agricultural foundations of early Historic cities and states drew upon the rich mixture of native species and adopted species that had been assembled by regional Neolithic and Chalcolithic societies. While some important species are known to have diffused from the Near East, several important species are native to India. Unfortunately, archaeological evidence is listed for documenting the use of these native species in a wild form by hunter-gatherers, followed by their transformation under cultivation into domesticated crops. In most cases our earliest finds come from communities where cultivation was already established. It would appear that most of the known Neolithic sites in South Asia come from periods of settling down for the long term and becoming more sedentary. The fact that these sites already show clear agriculture suggests that the origins lie earlier in more mobile societies, and less archaeologically visible sites.

Figure 10 The granite inselberg of Sannarachamma near modern Sanganakallu, a typical hilltop location for a South Indian Neolithic village site, view to Southwest, 1998.

Figure 11 Plan of the Southern Neolithic site of Budihal, indicating the substantial ashmound developed atop a large penning area, c. 2200 BC, and a small area of huts, 2200-1700 BC.

Also, further research on the biogeography of the wild progenitors of most native species is needed and more efforts at producing quantitative data through longer regional sequences of both botanical and zoological remains are also needed. Other emerging directions of research are the study of later hunter-gatherers and their interactions with established agricultural neighbors, and the study of the role of later Neolithic

Communities in the development of craft specialization, specialized crop production (such as fruits and fiber crops) and the regional trajectories toward social complexity. While there remains much research to be done, it is now clear that South Asia has several Neolithic traditions which participated in the recurrent social processes of domesticating plants and animals and creating economies of food production.

See also: Agriculture: Social Consequences; Animal Domestication; Asia, South: Baluchistan and the Borderlands; Ganges Valley; Paleolithic Cultures; Asia, West: Mesolithic Cultures; Ceramics and Pottery; Plant Domestication.

World History

World History