The magnificent Mesoamerican achievements attributed to the Classic period are all developed in the context of Neolithic Stone Age technologies, without draft animals, metal tools, and the plow, so familiar to Indo-European civilizations. This may appear to be a great disadvantage, but it was not. Maintaining animals is an additional production burden for farm families, and without that burden, the Mesoamerican farmers were able to focus entirely on their landscape. The domesticated plants from Mesoamerica include a shrub that produces chocolate or cacao and the orchid that produces vanilla. More plants in today’s markets have their origin in Mesoamerica than Europe, and maize is now a fundamental staple all over the world. The strength of the Mesoamerican agricultural strategy was founded on maize polyculture, relying on an intimate knowledge of the immediate habitat for subsistence. Working the landscape with both intensive infield home gardens and extensive outfield high-performance milpas shaped this subsistence system.

The dynamics of the Mesoamerican subsistence system utilized a rotational sequence for maintaining production. The system employs cutting and burning used as an environmental management tool at the outset. Then selecting, planting, and growing native plants, managing volunteer plants and cultivars to promote a managed regeneration dependent on the indigenous ecosystem. The high population levels of the Classic period correlate with an intensive agricultural and natural resource management scheme that was integrated into the subsistence system. This is a system still found today among traditional farmers. It relies on the smallholder farming strategy of investing knowledge and skill to increase the productivity of scarce fertile land versus the large-scale strategies of investing in capital improvements to increase the productivity of scarce labor. The result is a complex managed field design with domesticated crops and managed tree growth on fields once the maize crop cycle was complete.

The intensification of this essential system took on varied forms depending on the region and resources. Teotihuacan evolved a system in part employing irrigation of the arid plateau on which it is situated. Similarly, the Zapotec of highland Oaxaca relied on investments in flood water irrigation. In contrast, the humid lowlands of the Maya relied principally on rainfall agriculture with few land modifications such as at the great population center of Tikal. There are notable exceptions where either steep slopes required terracing or perennial swamps justified draining.

The Classic Maya

The Maya area, unlike the highland valleys in Mexico, is spread out across the tropical ridge lands and hills of lowlands, today a forested landscape rarely higher that 300 msl. Local topography of the absorbent limestone bedrock creates well-drained ridges interspersed with perched lakes and wetland depressions. Rain falls mainly between June and December and varies annually from 3000-4000 mm in the south to less than 500 mm in the northwest Yucatan. Drinking water during the dry season is scarce as there is little rain. The ancient Maya constructed reservoirs, or aguadas, to accommodate their dry season drinking water needs.

The Classic period has traditionally been hinged to the stone carving of the Maya calendar. The majority of the Classic period stelae have carved hieroglyphs and appear to commemorate marriages, alliances, meetings, and wars and could be viewed as the official history. The nature of this official history is fast being revealed with the combined research of linguistics, art, and archaeology. Once thought only to commemorate the worship of time, we now know that important political information is canonized on these stelae. The source of strife, the importance of coalitions, and the ritual of marriage highlight the reported regal relationships. Fractious and fragile, information on the stelae underscore the impact of the distant relationships, where centers were dispersed and the independence readily exerted in the absence of a strong capital as with Teotihuacan or Monte Alban.

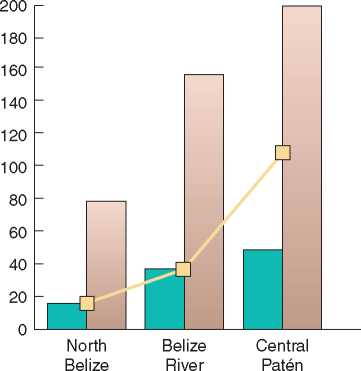

Farming settlements are distributed across the Maya area, clustering in the best agricultural zones of the well-drained upland ridges and hills that are unevenly dispersed across the lowlands. Centers are situated in prominent extensions of well-drained uplands, and the greater the extents, the higher settlement density, and the larger the centers (Figure 9). Nohmul, with 15 ha of public architecture, is one of the largest centers in Northern Belize. Settlement density is around 79 structures per sq km and the uplands cover only 15% of the local zone. The large center of El Pilar, located north of the Belize River, covers about 60 ha, has an average of 160 structures per sq. km distributed within the surrounding uplands that represent 39% of the zone. In contrast, Tikal, among the largest centers of the Classic period Maya covering more than 150 ha, supports up to 200 structures per sq km found predominantly in uplands that make up 49% of the local zone. Farmers were attracted to the good soils of the uplands and that was where the centers grew.

The Maya cultivated the forest as garden with maize polyculture and orchards with important fruit and hardwood tress as well as palms, managing cultivated fields in an orchestrated system of regeneration. Traditional Maya farmers today, drawing on their legacy, have one of the most diverse domestic systems on the planet. Signatures of their former gardens abound in the feral forest of today where 90% of the dominant plants of the forest are useful to people: avocado, allspice, vanilla, mahogany, cedar to name a few. This was created by millennia of accumulated knowledge and skill in the forest.

The economic landscape of the central Maya Lowlands

I I Settlement density (km2) I I Ridge lands (%)

I I Center size (in hectares)

Figure 9 Economic landscape of the central Maya Lowlands BRASS/El Pilar Program.

Many perishable elite materials such as colorful feathers for headdresses, resins for incense and gum, pelts for adornment, honey for sweetener, as well as cacao as a medium of exchange were produced in the lowlands. Most of these resources that would have balanced the trade between the highlands and lowlands could only dependably thrive in forested habitat. Consequently, the vitality of the Mesoamerican trade and exchange system, as well as Maya subsistence, depended on the management of the Maya forest as a garden.

The Maya lowlands are known for many centers, but Tikal was the largest by far (Figure 10). Tikal established its dominance in the Classic period around AD 250. By AD 600, the center held considerable sway over most of the southern lowlands. As Tikal was growing early on, the center embraced Mexican Teotihuacan themes that were prominently displayed on stelae and in architecture, yet these appear, like those of Zapotec of Monte Alban, to be translated into the local vernacular. Despite its evident influences, Tikal was subject to checks by neighbors, such as Uaxacthn, Caracol, Naranjo, and Calakmul vying for power. The growing interpretations of the hieroglyphic record attest to the delicate balance of power and alliance that was the charge of Classic Maya rulers. Texts carved in stone on stelae suggest tenuous coalitions punctuated by startling acrimony twisting and turning political events. These official texts were only one aspect of the story.

The juggling of power noted in the readings of the stelae of major centers can be seen in the lower-order settlements as well. Major centers have conspicuous temples and monuments to demonstrate their control of labor. Not so for the community level elite; it was their community production that would link them to the hierarchy.

The culmination of the Classic period Maya dates to around AD 900-1000. This is called the Classic Maya Collapse and is known for the abandonment of building and maintenance of the major centers, such as Tikal and El Pilar. It is said that the collapse

Figure 10 Tikal and the Peten Rainforest. Photograph by Macduff Everton 04505 m.

Was based on poor resource management and that today we are witnessing the repeat of those errors. Pollen and sediment data from lake cores south of Tikal have been interpreted as supporting this proposition. Yet today, the dominant plants of the Maya forest are replete with economic uses. Such a coincidence cannot be by chance. It is difficult to imagine that the Maya civilization, after having developed over more than 2000 years in Maya forest and supporting substantial populations, could have turned around to destroy it in only 100 years. New data demonstrate that the Maya adaptation was innovative and that the biodiversity of the Maya forest today is entirely anthropogenic.

The Maya Collapse represented a major change in Maya cultural traditions, but this did not occur all at one time or uniformly across the area. It has been assumed that the population underwent a major decline, but what is more likely is that the society transformed. There is no doubt that the maintenance of the major architecture and the support of the regal ritual traditions so elaborated in the Classic Period were indeed jettisoned, but there is no evidence that the populations disappeared. Major centers flourished north of the Tikal area after AD 1000. These include many of the major centers of the Yucatan, such as Chichen Itzii, Uxmal, Sayil, and Becan.

Far from disappearing, the Maya were present when the Spanish invaded Mesoamerica in the 1500s. Today, vital communities of Maya exist, impacted, as with all traditional communities, by the great changes wrought by globalization. Among them, traditional Maya farmers manage hundreds of plants in their own forest gardens and their knowledge of the forest demonstrates that it abounds with useful plants. Given these facts, it is obvious that the forest was not destroyed.

World History

World History