About AD 900 this pattern of incipient agriculture was overturned by settled peoples who lived in the valleys of major streams, built substantial dwellings capable of housing an extended family, and maintained a developed agricultural system. Gardens were prepared and tilled using sharpened bison scapulas lashed to a wooden handle. River floodplains supported small gardens containing maize, squash, and marshelder, to which were everywhere added beans, sunflowers, and gourds that contributed significantly to their diet, though bison hunting remained important. People were now tied at least seasonally to their fields though, like their historic descendants, they surely went on long-distance hunts on the High Plains, principally west of their villages.

Three major traditions may now be seen among the newly developed semi-sedentary gardeners along the eastern rim of the Central and Northern Plains. Each of them is believed to have developed, in ways that are not yet clear, from local Woodland origins. Their houses are larger than those of earlier times, and are capable of housing an extended family.

In the Central Plains small hamlets and the individual homesteads of these gardeners are known as the Central Plains Tradition, dating between about AD 900 and 1300. The tradition encompasses three major subdivisions: Upper Republican, along the Nebraska-Kansas boundary; Nebraska, along the Missouri River in

Nebraska and Iowa; and Smoky Hill, in north-central Kansas. Their hamlets of nearly square houses, set on terraces or hills above river floodplains, were supported by four or more center posts, and had a covered entry extending from one side; they were probably covered with earth. Bell-shaped pits were used for storing household goods and garden produce. Well-made globular pottery vessels and a wide range of utilitarian and nonutilitarian artifacts distinguish between these three subdivisions. Their small communities apparently enjoyed relative peace with their neighbors, for none is known to have been fortified.

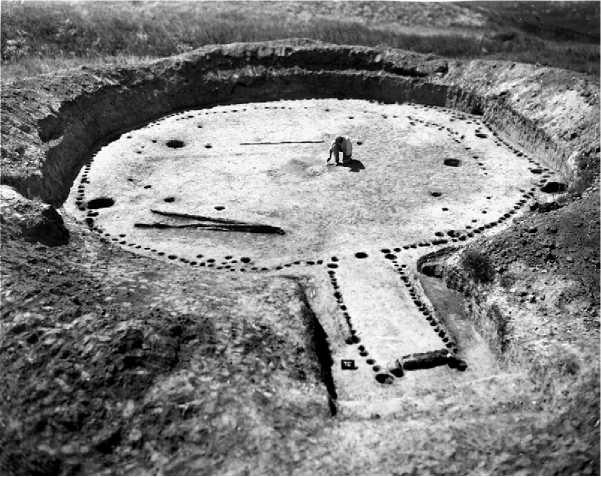

During the same time, to the north, along the banks of the Missouri and its major tributaries in northwestern Iowa and in North and South Dakota, was the Middle Missouri Tradition. Characterized by long rectangular gabled houses with extended entries on one end, they were clustered in villages of varying size, usually built on the rim of high terraces overlooking the river. The walls of their houses probably were banked with earth, but their roofs do not appear to have been covered with earth as were those in the Central Plains. Villages often were fortified by a ditch that enclosed the town margins not facing the riverbank, and was reinforced along its inner rim by a palisade of closely set posts, often augmented by bastions. It is clear that these people were menaced by some of their neighbors: perhaps by nomads, or perhaps by other villagers competing for the same resources. These communities evolved through three consecutive stages: the Initial, Extended, and Terminal Middle Missouri stages. Some Terminal Middle Missouri towns consisted of one hundred or more houses, tightly packed within bastioned defensive ditches (see Figure 6).

Sometime after about AD 1350 the distinctive architecture and artifacts of the Central and Middle Missouri Traditions become blurred, in what is known as the Coalescent Tradition. The architecture of the gardening tribes from Nebraska to North Dakota soon consisted of circular earth-covered lodges supported on a four-post foundation, and retaining a covered entry (see Figure 7). Dwellings of many early Coalescent sites are scattered and without visible defenses, but later ones are uniformly large and heavily fortified (Figure 5). The nature of the processes that led to these changes is obscure, but there is little doubt the Arikaras were responsible for introducing the new circular earthlodge in the north. The arrival of the Dakota Sioux from the Eastern Plains is presumed to be a major stimulus for their defensive measures.

The historic Siouan-speaking Mandan and Hidatsa Indians are lineal descendants of the Middle Missouri Tradition; the historic Caddoan-speaking Arikara and Pawnee Indians developed from the Central Plains Tradition. The Crows broke away from the Hidatsas in

Figure 6 Aerial view of Double Ditch State Historic Site, North Dakota, a prehistoric to historic Mandan Indian site. Photo by Russ Hanson, courtesy of National Park Service.

Figure 7 Early historic Arikara earthlodge floor, Cheyenne River site, South Dakota. (National Anthropological Archives, negative 39ST1-84).

Late prehistoric times to become nomads. Historically, a number of tribes along the eastern rim of the plains adopted the same general lifestyle just described for the earthlodge-dwelling tribes, including the Omahas, Poncas, and Otos. So did the Cheyennes and some of the Eastern Dakota Sioux - such as the Santees and Yanktonais - but in the historic period they abandoned this way of life for a fully nomadic one.

Though it is somewhat marginal to the Great Plains, in the late prehistoric period another major complex occupied the region extending from Lake Michigan to the Missouri River, and from southern

Minnesota to central Missouri, roughly centered on the state of Iowa. Sometimes called a ‘pottery culture’ because of its distinctive if highly variable ceramics, the Oneota Tradition emerged in about AD 900, probably having its antecedents in regional Woodland groups. They share many elements with village groups on the plains, including agriculture that used hoes made from bison scapulae.

Many Oneota sites are very large, some covering more than one hundred acres. Earthen enclosures are known at a few of them, and other sites are associated with burial mounds, though there are extensive cemeteries along the Missouri River, such as at the Blood Run site. The people were hunters, fishers, and gatherers who depended heavily on seasonally available resources near their villages. Maize was their major crop, but beans, squash, and sunflowers also were grown. Oneota culture persisted in many variants into the historic period, and has been identified as ancestral to the historic Chiwere Siouan-speaking Winnebago, Ioway, Otoe, and Missouri; and as the Dhegiha Siouan-speaking Osage, Kansa and, probably, the Omaha and Ponca tribes in the Central Plains and its margins.

World History

World History