Figure 13.37: Salt cones at Bilma awaiting Tuareg caravans, Nigeria. Source: Mike Barton

The Tuareg is a generic term given to camel herders who live in the desert borderlands between Algeria, Niger, and Mali, but who are composed of a multitude of tribes with different languages and varying customs depending on location.23 There is a well-defined social structure composed of three classes: nobles, vassals, and slaves. They call themselves by names such as Kel Tamasheq or Kel Tamajaq (“Speakers of Tamasheq”) and are most certainly descended from ancient Saharan peoples from the north. Around 500 ce, they expanded southward, becoming a major player in transcontinental trade of gold and salt (Figure 13.37). Their legendary queen Tin Hinan is credited in Tuareg lore with uniting the ancestral tribes and founding the unique culture that continues today. At Abalessa, in southern Algeria, there is a grave that is thought to be hers. While considerable variation exists between the difi'erent groups, social strata exist within all of them, with powerful nobles assuming leadership. These groups, called a “drum group” (ettebel), will unify for caravan treks. The Tuareg are matrilineal, though not matriarchal. Unlike many Muslim societies, the women do not traditionally wear a veil, but the men do. They are only taken ofi' in the presence of close family. Tuareg men find shame in showing their mouth or nose to strangers or people of higher standing than themselves. The veil is a 3- to 5-meter-long, indigo-dyed cotton combination of turban and veil.

The salt caravan traveling east to Bilma, Nigeria, is one of their most important activities. It is always difficult and every year camels are lost or die of fatigue or infections from wounds cause by poorly arranged loads. Preparation is extensive. Men will choose the best camels, buy goods (wheat, textiles, dried meat, sugar, coffee, tobacco, tools, and more) to exchange for ropes and for hay bales to feed the camels during the desert crossing. Meanwhile, the locals at Bilma accumulate a large number of salt bars, dug up in open-air mines or from salt drying on the surface.

Wood and metal implements are made by a special group of smithies, known as the In-adan, who also make the knives, daggers, spears, and shields. The Inadan have a complex and ambiguous relationship to the Tuareg. Though not considered Tuareg, they are essential to the Tuareg for they make all of their equipment including jewelry and saddles. Their fellow Tuareg view them with some suspicion or apprehension because of their metallurgical skills, which are associated with a mystic power known as ettama. They also speak their own language, are given immunity during periods of conflict, and ofl:en serve as ambassadors operating between Tuareg families and groups. To attack an Inadan is to repudiate oneself, but how this relationship was established and when is still a riddle.

Each household has one compound, which usually consists of a single family. In the Air dialect of Tamacheq, gara refers to the compound enclosure. Women say, “those of the gara eat together.” This creates a distinction between insider and outsider status. The typical tent (edew or ehan) is constructed of palm flber mats on a wooden frame. Ehen denotes both the tent and marriage. The tent is, in fact, built during a wedding by the elderly female relatives of the bride as her dowry and it is thereafl:er owned by the married woman. She may eject her husband from it if they quarrel or divorce. Afl:er one year of marriage, there is a ritual called “greeting the tent,” when the bride’s sisters-in-law come to her to show respect. They sing special songs in praise and humor.

Though some compounds may now have mud houses, the tent remains the centerpiece of the compound. It will be usually located near the woman’s mother’s compound and she will merge her livestock with her mother’s for the flrst two or three years of marriage until bridewealth payments and gifl:s from the groom are completed. Only then may the couple decide to move away. Afl:er a birth, the mother and baby remain in a special tent behind a windscreen for forty days, for protection against spirit attacks to which a new mother and baby are viewed as especially vulnerable. On the evening before the official Islamic naming day the baby is taken by elderly female relatives in a procession around the baby’s mother’s compound “in order to show it the world.” When a woman dies, her tent is destroyed and the land beneath it is left enclosed with a fence for about a year. The mats are distributed as alms. In comparison, men’s mud houses are not destroyed on their deaths, but inherited usually by the sons.

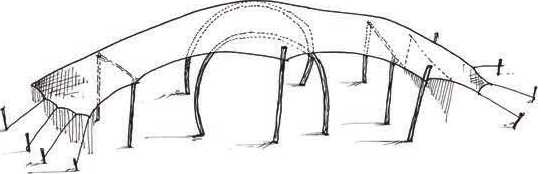

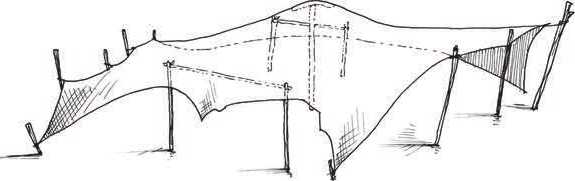

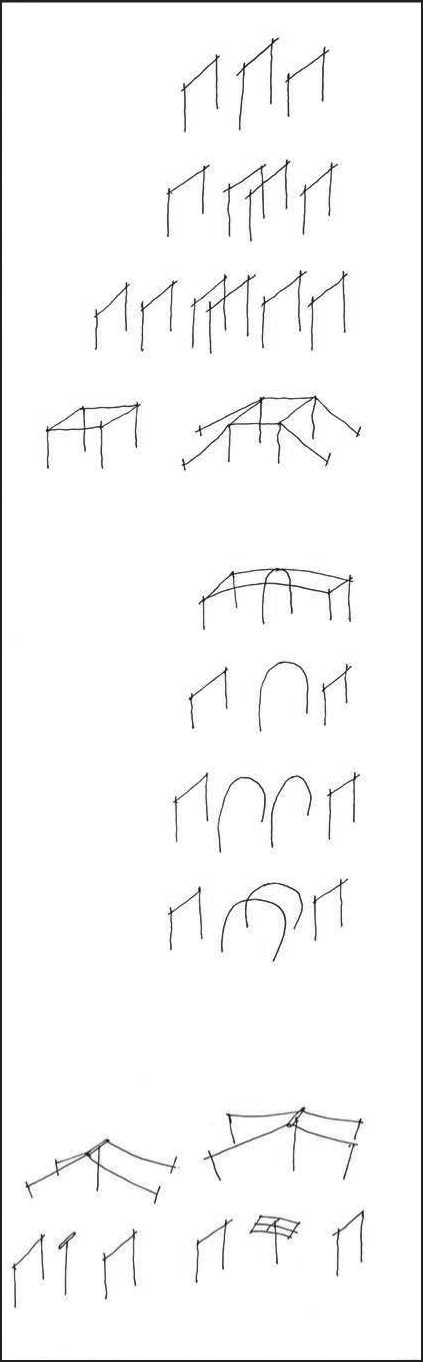

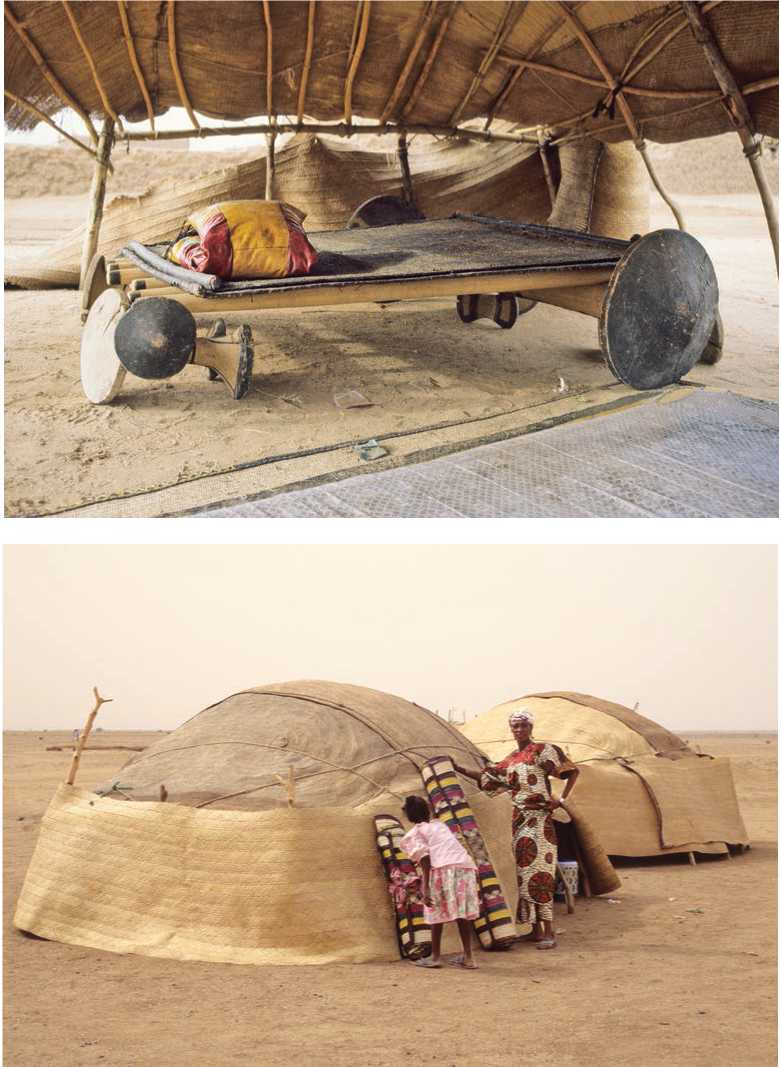

When a structure is to be made, a sandy spot is chosen and cleared of rocks and bushes. The bed is set up flrst. It is made of beautifully carved poles with a mat as a mattress. A forked pole is driven into the ground nearby. This holds a food bowl out of reach of any animals that may wander into the tent. With these furnishings in place, the tent is ready to be pitched. First the curved pieces of the arch are lashed together and, depending on the size of the tent, two or four of these are placed parallel to each other. First, the vertical posts of the arch are driven into the ground at each end. Horizontal poles are then tied along the sides to hold it together. A cord is wound around the central arch that will be used to fasten thin rafter strips, which are bent across the arches and inserted between the cord and the arch to form the roof structure. The frame is made of long acacia roots. To make them pliable, the roots are heated over a flre, bent, and held in position by ropes. When dry, they hold their contorted shape (Figure 13.38).

The mats are unrolled across the roof and the walls are erected and tied to the frame. These mat-coverings of the tent are made of palm leaves, which are plaited by hand into narrow strips of about a hand’s width. These are sewn together with large needles into an oval mat, several of which are used for the roof cover. The wall mats are made of straw and grass with leather weft strips woven in decorative patterns (Figures 13.39, 13.40).

Figure 13.38: Tent plans, Tuareg, Niger. Source: Finbarr O’Reilly/Reuters

Figure 13.40: Tuareg, Niger. Source: Charles O. Cecil

Figure 13.39: A Tuareg bed in the tent, Agadez, Niger. Source: Charles O. Cecil

Sometimes in good weather only the roof is constructed and the walls are left out, creating a flatter version of the structure. Though the structure appears flimsy, it can actually withstand the worst of Sahara dust storms. The walls provide lateral reinforcement and keep sand out. These tents are mainly used in the dry season. After a long rain the mats need to be removed and dried.

The centerpiece of the tent is the bed, which is itself a kit of parts. Made by the Inadan, it is a masterpiece of design, consisting of two “axles” elevated from the desert floor on drumshaped elements. Although tents are still in use, over the last thirty years many Tuareg have become sedentary and now live in adobe or cement-block houses in towns and cities. The introduction of a cash economy in the last decades has also signiflcantly altered their lifestyles, as had the arrival of roads and trucks.

ENDNOTES

1. Andrew Sherratt, “The Horse and the Wheel: The Dialectics of Change in the Circum-Pontic and Adjacent Areas, 4500-1500 bc,” Prehistoric Steppe Adaptation and the Horse, eds. Marsha Levine, C. Renfrew, and K. Boyle (Cambridge, UK: McDonald Institute Monographs, 2003): 233-252.

2. Ludmila Koryakova, “Some Notes About Material Culture of Eurasian Nomads,” Kurgans, Ritual Sites, and Settlements: Eurasian Bronze and Iron Age, eds. Jeannine Davis-Kimbal et al. (Oxford: Archaeopress, 2000): 13-18; Stephanie N. Dudd, Richard P. Evershed, and Marsha Levine, “Organic Residue Analysis of Lipids in Potsherds from the Early Neolithic Settlement of Botai, Kazakhstan,” Prehistoric Steppe Adaptation and the Horse: 45-53.

3. Sandra Olsen, Bruce Bradley, David Maki, and Alan Outram, “Community Organization among Copper Age Sedentary Horse Pastoralists of Kazakhstan,” Beyond the Steppe and the Sown, eds. D. L. Peterson, L. M. Popva, and A. T. Smith (Leiden: Brill, 2006): 89-111.

4. Ludmila Koryakova and Andrej Vladimirovich Epimakhov, The Urals and Western Siberia in the Bronze and Iron Ages (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2007): 72-73.

5. The area is also home to a large number of rock art drawings dating from 6000-1000 bce.

6. Der Skythenzeitliche Furstenkurgan Arzan 2 in Tuva, eds. Konstantin Von Cugunov, Anatoli Nagler, and Hermann Parzinger (Mainz: Philipp von Zabern 2010); Andrey Yu. Alekseev, N. A. Bokovenko, Yu. Boltrik, et al. “Some Problems in the Study of the Chronology of the Ancient Nomadic Cultures in Eurasia, (9th-3rd Centuries bc),”Geochronometria 21 (2002): 143-150.

7. Jeannine Davis-Kimball, “The Beiram Mound, a Nomadic Cultic Site in the Altai Mountains (Western Mongolia),” Kurgans, Ritual Sites, and Settlements, Eurasian Bronze and Iron Age: Part II, Archaeological Excavations, eds. Jeannine Davis-Kimball, Eileen M. Murphy, Ludmila Koryakova, and Leonid T. Yablonksy (Oxford: Archeopress, 2000): 89-105. [Www. csen. org/BAR%20Book/ BAR.%20Part%2001.TofC. html] [accessed March 20, 2012].

8. Caroline Humphrey Waddington, “Horse Brands of the Mongolians: A System of Signs in a Nomadic Culture,” American Ethnologist 1, no. 3 (August 1974): 471-488.

9. Byambyn Rinchen, “A propos de la Sigillographie Mongole,” Acta orientalia Academiae scientiarum hungaricae 3, no. 1-2 (1953), cited in C. H. Waddington, “Horse Brands of the Mongolians,” Ibid., 471-488.

10. Giovanni (da Pian del Carpine, Archbishop of Antivari), The Story of the Mongols Whom We Call the Tartars, translated by Erik Hildinger (Boston: Branden, 1996): 41.

11. Peter Alford Andrews, “From Rashidiya to the Ordos: In Search of Early Mongol Tents.” Technology, Tradition and Survival: Aspects of Material Culture in the Middle East and Central Asia, eds. Richard Tapper and Keith McLachlan (London: Frank Cass, 2003): 150-151.

12. Julia Ann Gray, “The Mongolian Yurt: A Problem of Human Space and Aesthetic Form” (Master’s thesis, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, 1987); Gary Seaman, Foundations of Empire: Archaeology and Art of the Eurasian Steppe (Los Angeles: Ethnographics Press, 1992): 147; Peter A. Andrews, Felt Tents and Pavilions: The Nomadic Tradition and Its Interaction with Princely Tentage (London: Melisende, 1999).

13. Carole Pegg, Mongolian Music, Dance, and Oral Narrative: Performing Diverse Identities (Seattle: University of Washington Press, 2001): 188.

14. Ronald G. Knapp, China’s Old Dwellings (Honolulu: University of Hawaii Press, 2000): 318-320; Sechin Jagchid and Paul Hyer, Mongolia’s Culture and Society (Boulder, CO: Westview Press, 1979): 64.

15. See David Sneath, “The Obo Ceremony in Inner Mongolia: Cultural Meaning and Social Practice,” in Altaic Religious Beliefs and Practices, Proceedings of the 33rd Meeting of the Permanent International Altaistic Conference, Budapest, June 24-29, 1990, eds. Geza Bethlenfalvy et al. (Budapest: Research Group for Altaic Studies, Dept. of Inner Asiatic Studies, Eotvos Lorand University, 1992): 309-317.

16. Tatal Asad, The Kababish Arabs: Power, Authority and Consent in a Nomadic Tribe (New York: Praeger, 1970): 37-40.

17. Harold C. Fleming, The Age-Grading Culture of East Africa: An Historical Inquiry. (Pittsburgh: University of Pittsburgh, 1965).

18. Merwan Engineer, Eric Roth, and Linda Welling, “An Almost Exact Overlapping Generations Model of the Rendille of Northern Kenya.” Paper presented at the Canadian Economics Association Meetings (January 2005), Http://web. uvic. ca/~menginee/mypapers/Exact. pdf (accessed April 22, 2012): 4-6.

19. Gunther Schlee, Das Glaubens - und Sozialsystem der Rendille: Kamelnomaden Nord-Kenias (Berlin: Dietrich Reimer, 1979): 83-87.

20. Wilhelm J. G. Mohlig and Rudiger Koppe, “Concepts of Violence and Peace in African Languages,” in Healing the Wounds: Essays on the Reconstruction of Societies after War, eds. Marie-Claire Foblets and Trutz von Trotha (Portland, OR: Hart Publishing, 2004): 25-46.

21. This is condensed from the discussion in Labelle Prussin, African Nomadic Architecture: Space, Place, and Gender (Washington: Smithsonian Institution Press, 1995): 155-165.

22. Shun Sato, “The Rendihe Subsistence Groups Based on Age-System,” African Study Monographs, Supplementary Issue 3 (March 1984): 46-47.

23. Robert F. Murphy, “Social Distance and the Veil,” American Anthropologist 66, no. 6 (December 1964): 1257-1274; S. Colman, Tuareg (Lincoln Park, MI.: Dawn Press, 1980); Kenneth Slavin and Julie Slavin, The Tuareg (London: Gentry Books, 1973); Karl G. Prasse, The Tuaregs: The Blue People (Copenhagen: Museum Tusculanum Press, 1995); Kristyne Loughram, “The Stuff of Life, Tent, Food, Weapons,” The Art of Being Tuareg: Sahara Nomads in a Modern World, eds. Thomas K. Selig-man and Kristyne Loughram (Los Angeles: Iris and Gerald Cantor Center for Visual Arts at Stanford University): 90-91.

World History

World History