Although works of anthropological significance have a considerable antiquity—about 2,500 years ago the Greek historian Herodotus chronicled the many different cultures he encountered during extensive journeys through territories surrounding the Mediterranean Sea and beyond, and nearly 700 years ago far-roving North African Arab scholar Ibn Khaldun wrote a “universal history”— anthropology as a distinct field of inquiry is a relatively recent product of Western civilization. The first anthropology program in the United States, for example, was established at the University of Pennsylvania in 1886, and the first doctorate in anthropology was granted by Clark University in 1892. If people have always been concerned about their origins and those of others, then why did it take such a long time for a systematic discipline of anthropology to appear?

The answer to this is as complex as human history. In part, it relates to the limits of human technology. Throughout most of history, the geographic horizons of people have been restricted. Without ways to travel to distant parts of the world, observation of cultures and peoples far from one’s own was a difficult—if not impossible— undertaking. Extensive travel was usually the privilege of an exclusive few; the study of foreign peoples and cultures could not flourish until improved modes of transportation and communication developed.

This is not to say that people have been unaware of the existence of others in the world who look and act differently from themselves. The Old and New Testaments of the Bible, for example, are full of references to diverse ancient peoples, among them Babylonians, Egyptians, Greeks,

Anthropology The study of humankind in ah times and places.

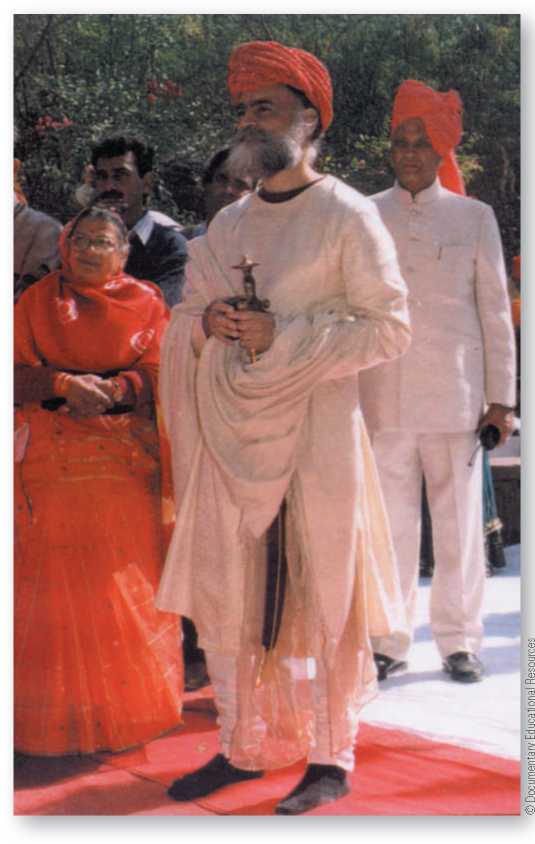

Anthropologists come from many corners of the world and carry out research in a huge variety of cultures all around the globe.

Dr. Jayasinhji Jhala, pictured here, hails from the old city of Dhrangadhra in Gujarat, northwestern India. A member of the Jhala clan of Rajputs, an aristocratic caste of warriors, he grew up in the royal palace of his father, the maharaja. After earning a bachelor of arts degree in India, he came to the United States and earned a master's in visual studies from MIT, followed by a doctorate in anthropology from Harvard. Currently a professor and director of the programs of Visual Anthropology and the Visual Anthropology Media Laboratory at Temple University, he returns regularly to India with students to film cultural traditions in his own caste-stratified society.

Jews, and Syrians. However, the differences among these people are slight in comparison to those among peoples of arctic Siberia, the Amazon rainforest, and the Kalahari Desert of southern Africa.

The invention of the magnetic compass allowed seafarers on better-equipped sailing ships to travel to truly faraway places and to meet people who differed radically from themselves. The massive encounter with previously unknown peoples—which began 500 years ago as Europeans sought to extend their trade and political

Domination to all parts of the world—focused attention on human differences in all their amazing variety. With this attention, Europeans gradually came to recognize that despite all the differences, they might share a basic humanity with people everywhere. Initially, Europeans labeled these societies “savage” or “barbarian” because they did not share the same cultural values. Over time, however, Europeans acknowledged such highly diverse groups as fellow members of one species and therefore as relevant to an understanding of what it is to be human. This growing interest in human diversity coincided with increasing efforts to explain findings in scientific terms. It cast doubts on the traditional explanations based on religious texts such as the Torah, Bible, or Koran and helped set the stage for the birth of anthropology.

Although anthropology originated within the historical context of European cultures, it has long since gone global. Today, it is an exciting, transnational discipline whose practitioners come from diverse societies all around the world. Many professional anthropologists born and raised in Asian, African, Latin American, or American Indian cultures traditionally studied by European and North American anthropologists contribute substantially to the discipline. Their distinct non-Western perspectives shed new light not only on their own cultures but on those of others. It is noteworthy that in one regard diversity has long been a hallmark of the discipline: From its earliest days, women as well as men have entered the field. Throughout this text, we will be spotlighting individual anthropologists, illustrating the diversity of these practitioners and their work.

World History

World History