Angkor Site of a series of capital cities of the Khmer empire for much of the period from the ninth century to the fifteenth century CE.

Buddhism A non-theistic religion, a philosophy, and a system of psychology pronounced by Buddha.

Cham civilization An ancient civilization of the Quang-nam (where Dong-duong is located), Amaravati, Vijaya (the present-day Bihn-dinh), and Pandurang regions.

Dvaravati Kingdom of the Mon people that existed from the sixth to the eleventh centuries. It was centered on the Chao Phraya River valley in modern-day Thailand, with Nakhon Pathom as the capital.

Hindu religion A diverse body of religion, philosophy, and cultural practice native to and predominant in India.

Inscriptions Words or letters written, engraved, painted, or otherwise traced on a surface and can appear in contexts both small and monumental (coin texts and monumental carvings on buildings are both included by historians as types of inscriptions).

Pyu (also written Pyuu, or Pyus) An ancient series of city-states (and their languages) found in the central and northern regions of what is now Myanmar (Burma), between the first century BC and the ninth century AD, approximately 100BC through 840AD.

Sanskrit An ancient Indic language that is the language of Hinduism and the Vedas and is the classical literary language of India.

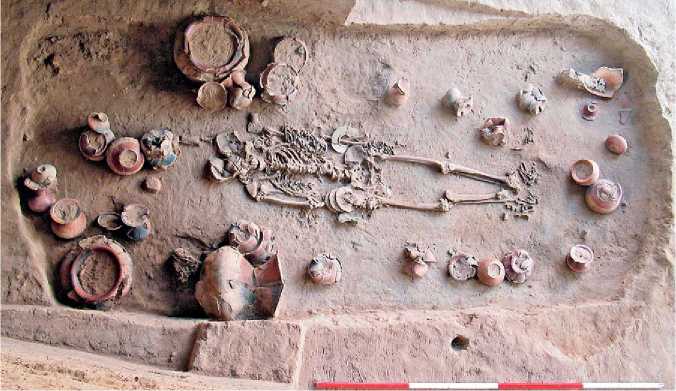

During the course of the second and first millennia BC, communities living in much of lowland Southeast Asia progressively became more socially complex. Until recently, it was widely noted that the Bronze Age, dating between about 1300 and 500 BC, failed to reveal the rise of social elites. This is most unusual, since the control and ownership of metal is commonly accompanied by such social change. However, major excavations at the site of Ban Non Wat in northeast Thailand have uncovered a small number of exceptionally rich burials, in which the dead were accompanied by bronze artifacts, up to 80 or 90 large pottery vessels and an astonishing amount of exotic personal jewelry (Figures 1 and 2). Such social divisions, between rich leaders and the majority of the population, continued into the Iron Age. At Shizhaishan in Yunnan Province of China, for example, there is a royal necropolis. One large grave actually contains a gold seal inscribed ‘the seal of the King of Dian’, a seal probably given to the king by the Han Emperor himself. Further south, burials at the Iron Age site of Noen U-Loke near Ban Non Wat were found with gold, silver, glass, agate, and carnelian jewellery, set in clay-lined graves filled with rice. Sites like Noen U-Loke were ringed by multiple moats and banks that would have required a very large and organized labor force.

Documentation of these prehistoric communities and their cultural sophistication is an important step in understanding the rise of civilizations. Concentration by generations of French scholars on the physical remains of sacred historic sites and the associated inscriptions, largely written in the Sanskrit language of India, led to the idea that civilizations resulted from the process of Indianization. This involved the adoption of Indian religions (Hinduism and Buddhism), Indian architectural styles, and the Sanskrit or Pali languages by the undeveloped local peoples. We can now appreciate how complex Southeast Asian leaders might have selectively adopted Indian ways to elevate their status and, in doing so, founded their own states.

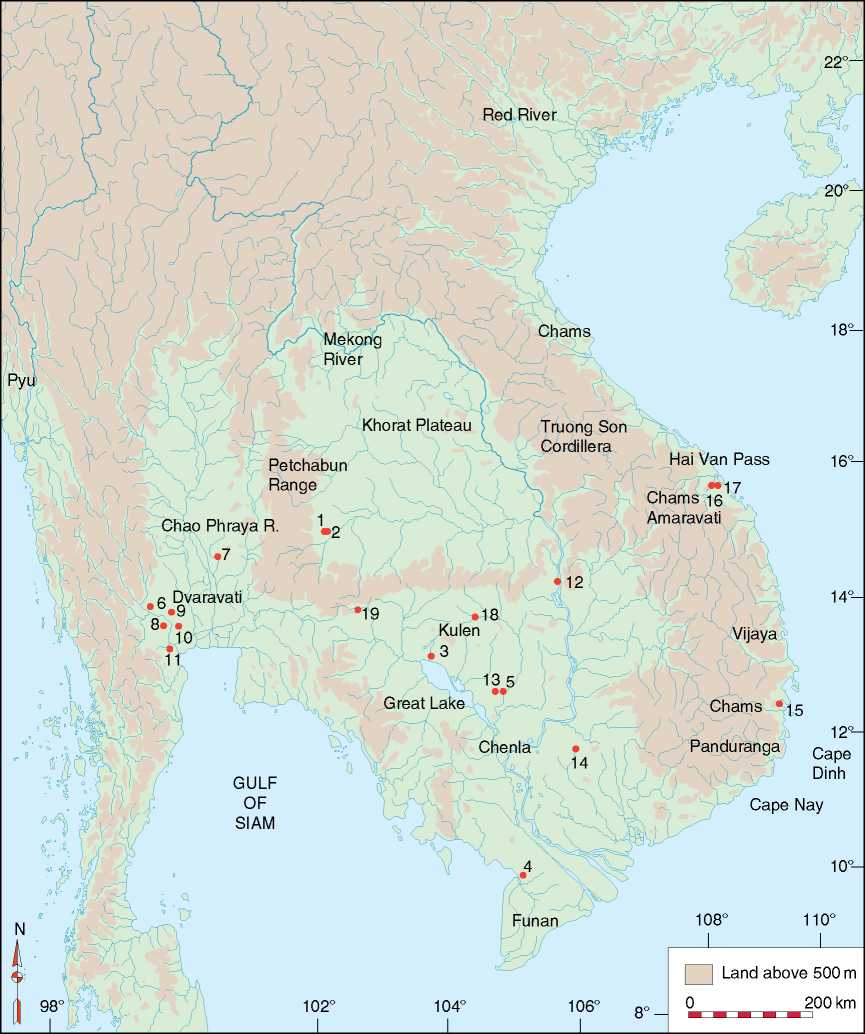

There is a sharp boundary between the situation in Southeast Asia west of the Truong Son Cordillera and south of the Red River Delta, and the regions to the north (Figure 3). This reflects the imperialist policies of the Qin Emperor and his Western Han successors. They sent armies south, carved off new provinces (known as commanderies), and extinguished the power and status of local leaders. The rest of mainland Southeast Asia, beyond the reach of imperial China, witnessed a series of distinct civilizations each with their own language, traditions, religion, and pattern of rise and decline. These were mainly riverine. Rice was their economic prop, and all engaged

Figure 1 This rich Bronze Age burial from the site of Ban Non Wat reveals the presence there of social elites, already, by about 1000 BC.

Figure 2 This row of very rich Bronze Age burials from Ban Non Wat in Northeast Thailand clearly illustrates the wealth of prehistoric communities prior to the emergence of early states.

In widespread trade in goods and ideas. Warfare was endemic. In the lower reaches of the Mekong River, we encounter a succession of states often named as Funan, Chenla, and Angkor (Figure 4). The state of Dvaravati occupied the Chao Phraya River, while the river valleys flowing east from the Truong Son Range sustained the Chams. To the east, we encounter the Pyu in Central Myanmar (Burma), while a civilization developed on the Arakan coast. These states should not be perceived as monolithic civilizations. The reality was more subtle: authority

And power were probably flexible and dependent on the charisma of individual leaders. Like a concertina, states could expand and contract rapidly. Even during the life of the great civilization of Angkor, establishing or maintaining control over peripheral princes was not easy, and was rarely, if ever, achieved. Hence, when talking of Dvaravati, we are probably in touch with a kaleidoscopic situation of many rival rulers, and with Champa, each river valley had its own polity with little evidence of central hegemony.

1. Ban Non Wat, 2. Noen U-Loke, 3. Angkor, 4. Oc Eo, 5. Ishanapura, 6. Ban Don Ta Phet, 7. Ban Tha Kae,

8. Pong Tuk, 9. U-Thong, 10. Nakhon Pathom, 11. Ku Bua, 12. Sambhupura (approximate location), 13. Wat En Khna, 14. Banteay Prei Nokor, 15. Po Nagar, 16. My Son, 17. Dong Duong, 18. Koh Ker, 19. Banteay Chmar

Figure 3 Southeast Asia showing the sites mentioned in the text, followed by the list of sites.

World History

World History