The Adena culture developed into several regional sub-cultures that are known collectively as the Hopewell Tradition (200 bce-500 ce). Like the Adena before them, they had ancestor and shaman cults. And like the Adena, they were a widespread but tightly knit network of clans. But their difierences with the Adena are noticeable. The Hopewell, the inheritors of the commodity wealth of the region, became, one could say, almost pure ceremonialists, guarding over and giving drama to one of the prime sacred landscapes in all of North America.26 They were no longer just riverine specialists, but ceremony specialists. Their mortuary complexes were larger and better organized than the Adena and their shamanistic practices were more powerfully expressed. The Hopewell also excelled in producing ritual paraphernalia, especially when it came to the working of copper. Brought down from the area around Lake Michigan, copper was hammered into thin sheets that in turn were fashioned into breastplates, ear decorations, and shamanistic objects. Some had the shape of a hand, others represented birds or abstract figures with patterns on them made by the careful application of salts and acids. In some cases the drawing involved an intricate play of positive and negative shapes. Stone and turtle shells were also crafted into exquisite objects, all of which would have been just as amazing and magical to visitors back then as they are to museum-goers today (Figures 6.17, 6.18, 6.19, and 6.20).

Figure 6.17: White-Fronted Goose efhgy and pipe, Hopewell culture. Source: Courtesy of the Ohio Historical Society

Figure 6.18: Efhgy human hand, Hopewell culture. Source: Courtesy of the Ohio Historical Society

Figure 6.20: Vessel, Hopewell culture. Source: Courtesy of the Ohio Historical Society

Figure 6.19: Copper cut out, Hopewell culture. Source: Courtesy of the Ohio Historical Society

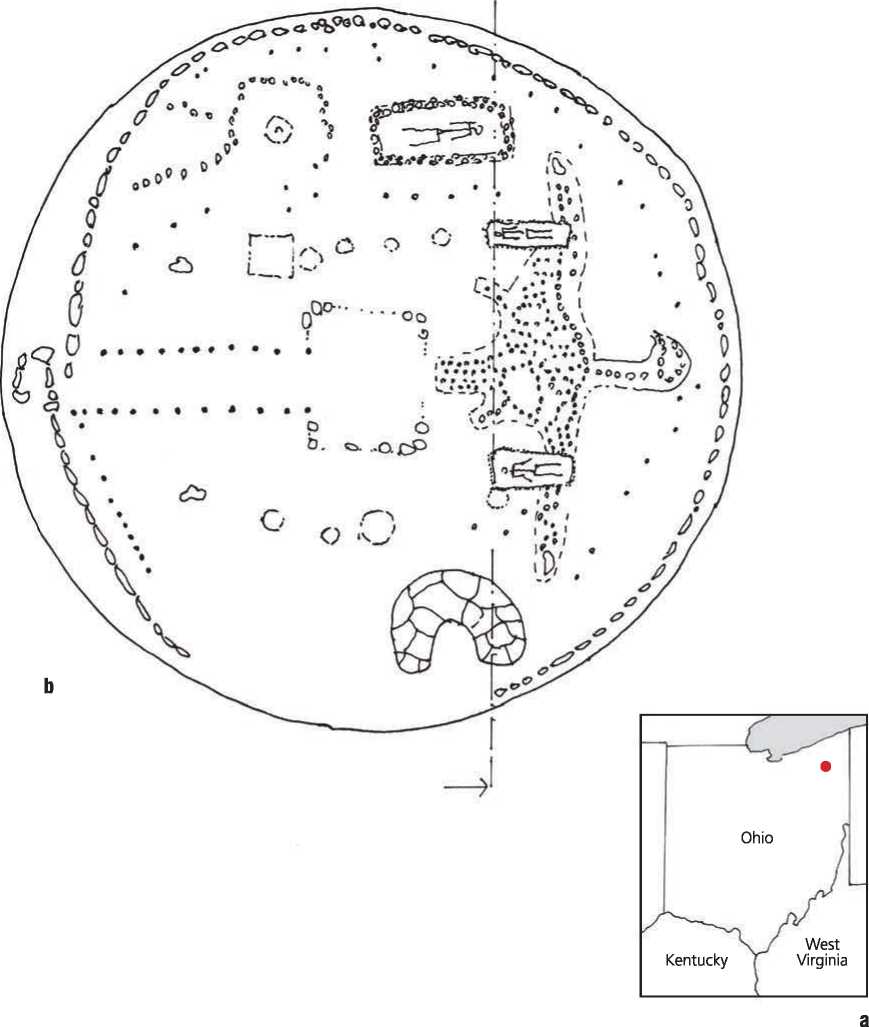

Although the specific role of these objects in the ceremonies cannot be re-created, it is clear that earthworks were a central element. They consisted of mounds, as well as of huge enclosures in the shape of squares, circles, and octagons. Members of difierent residential groups, separated by varying geographic and social distances, would establish or renew essential relationships with one another by building these earthworks, performing rites within them, negotiating marriages, and forming ritual exchange partnerships and trade.

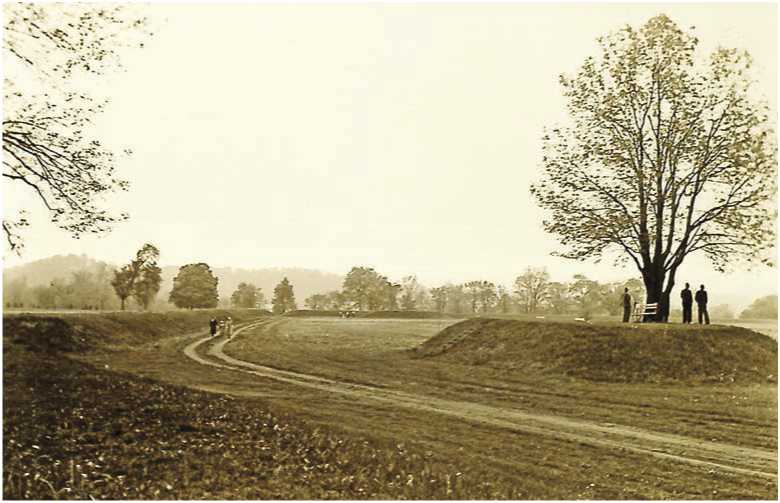

Hopewell earthworks are ofi:en composed of a square and a circle in some combination, defined by earthen berms ranging from 1 to 4 meters high and having sides measuring 200 or even up to 300 meters! The walls have breaks in them at the corner and at the middle of each side. A “marker” mound sits just interior to each of the breaks. An old photograph of Newark shows

The enclosure wall to the left and to the right, a mound (Figure 6.21). The marker mounds have no burials associated with them, and must have been used as “protector” mounds guarding the sanctity of the plaza. Some of the mounds, however, are ancestor mounds, with some inside the squares and others nearby. Seip had a total of fourteen known burial mounds within and immediately outside of the square.

Figure 6.21: Newark Mound Group, Newark, Ohio, USA. Source: Courtesy of the Ohio Historical Society

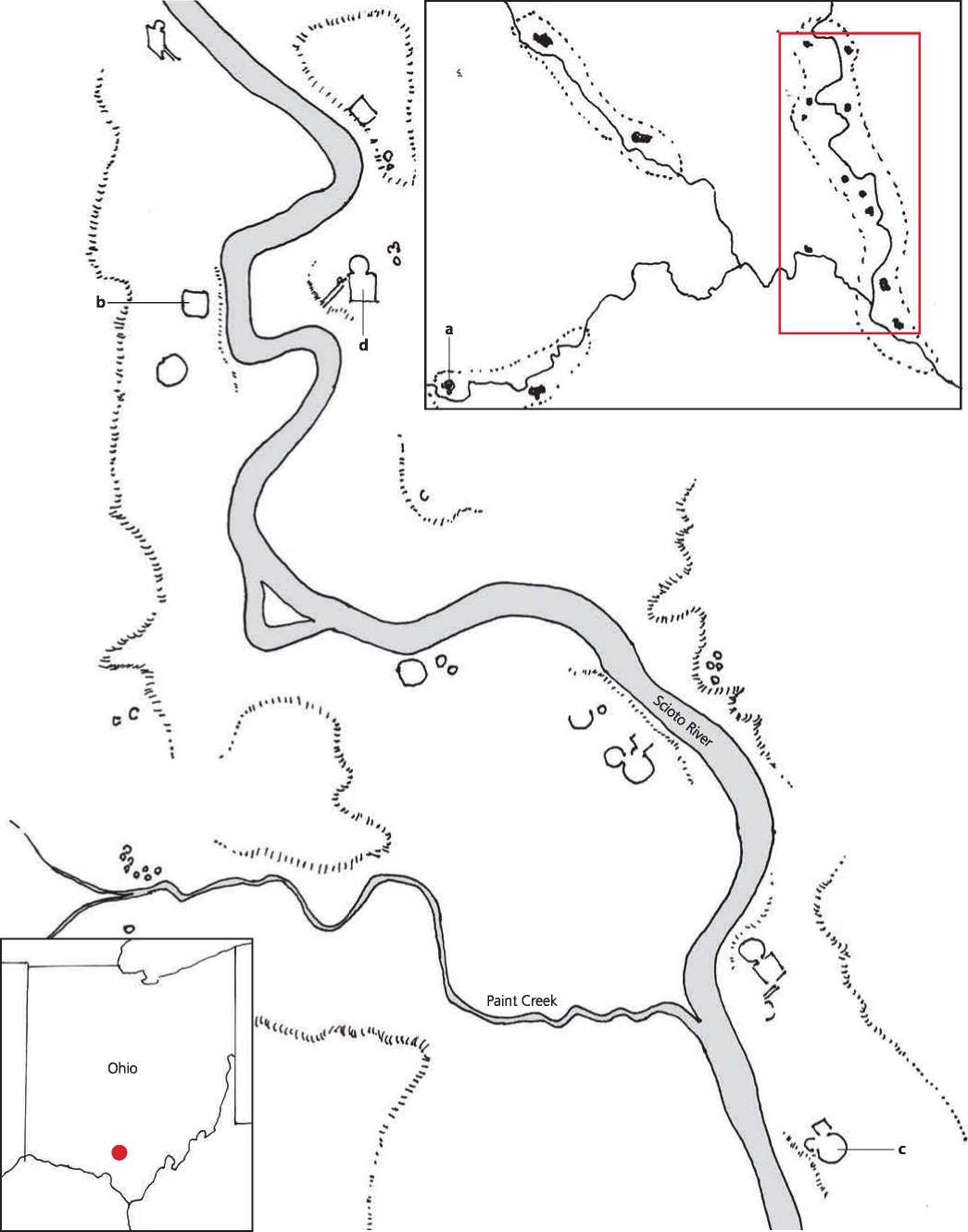

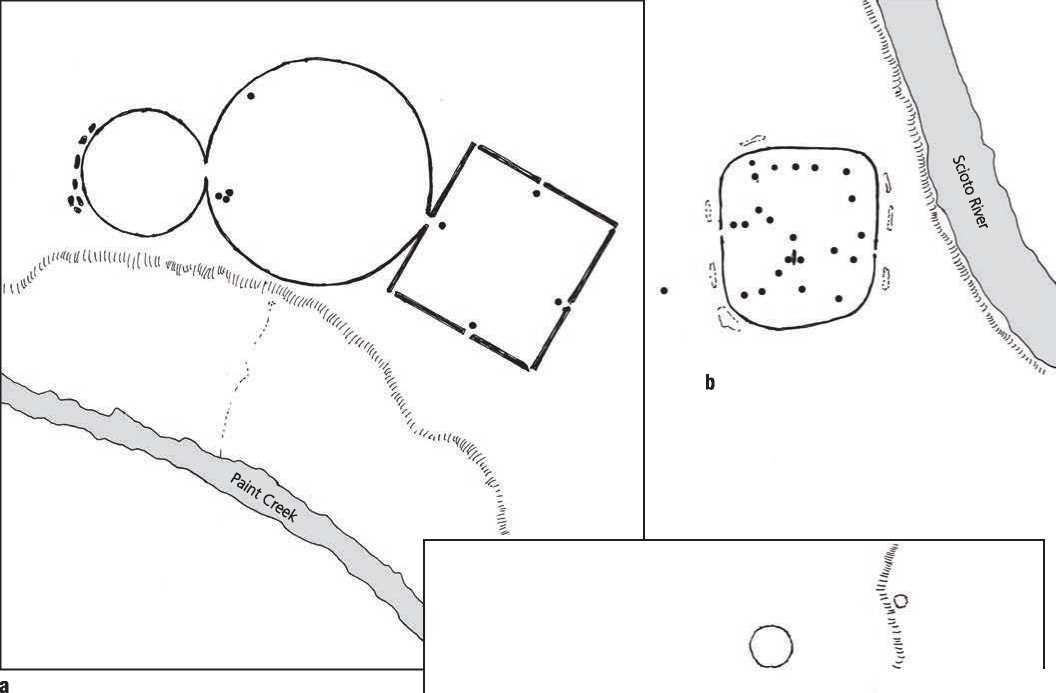

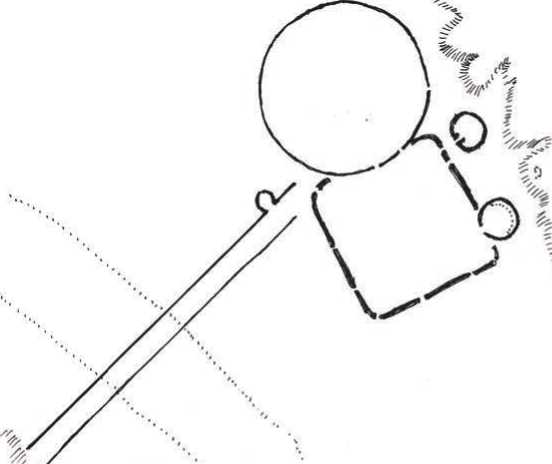

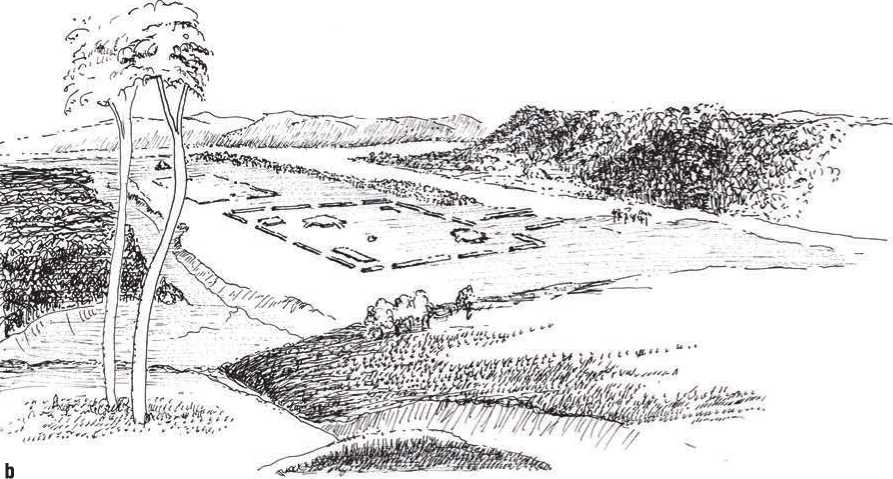

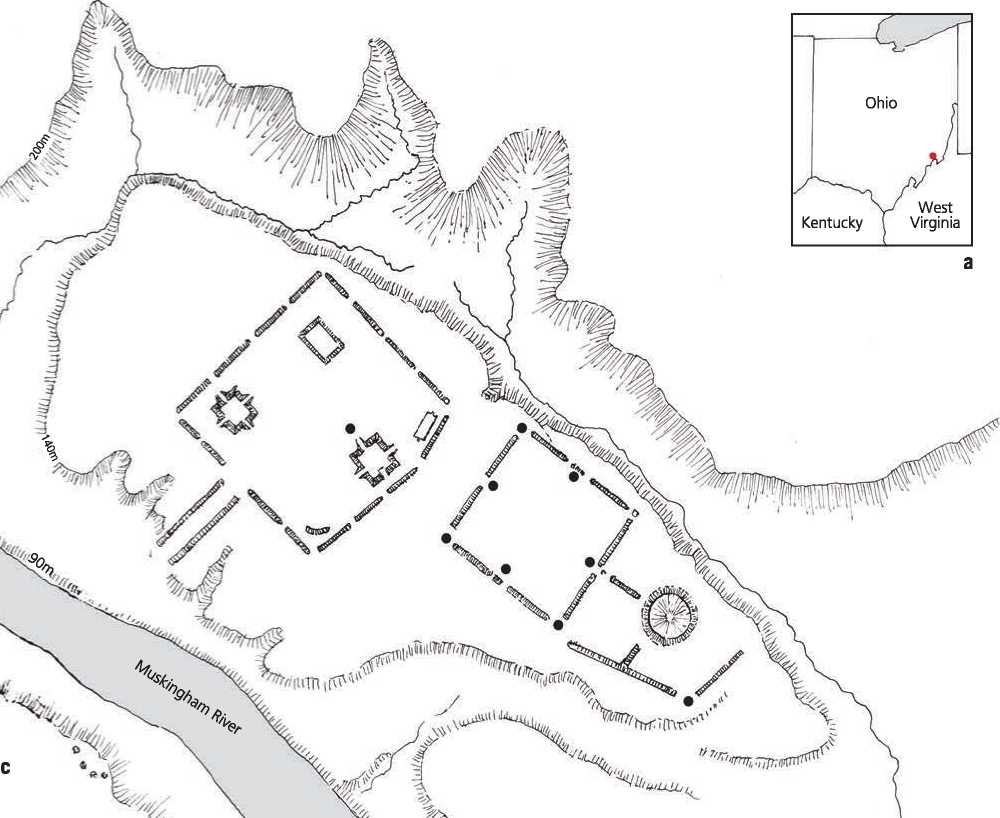

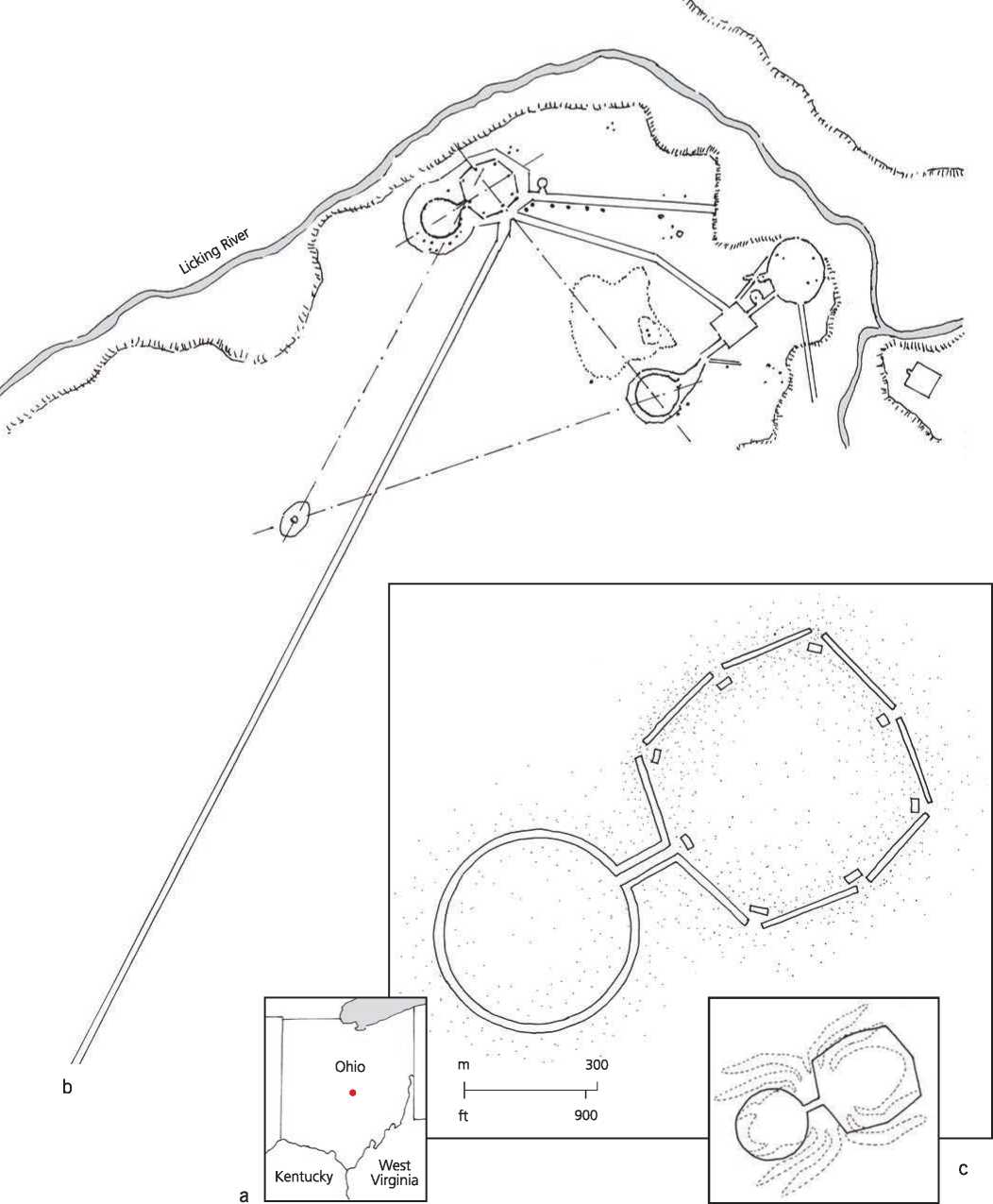

Though Hopewell sites extended beyond southern Ohio, the Scioto River, between Chillico-the and the river’s intersection with the Ohio River, was certainly its heartland (Figures 6.22 and 6.23a, 6.23b, 6.23c, 6.23d). Within 9 kilometers of Chillicothe there are at least thirteen large sites. In fact, moving up the Scioto River from the Ohio, a visitor would have seen a continuous rhythm of ritual complexes up on the bluffs. Once past Chillicothe the visitor would move northeast to Newark Mounds. A ceremonial road led to Newark, running perfectly straight for kilometers through the tall grass of the rolling Ohio prairie. Visitors were expected to approach settlements by these roads, but how? And how do these roads relate to the ceremonial gathering?

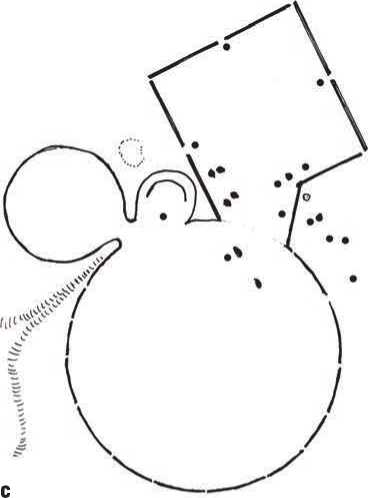

Unlike most of the earthwork settlements, which are in woodlands, the Newark earthwork was on the open prairie, on a bluff at a bend in the river, and thus was a site with great visibility. Its extraordinary collection of mounds, enclosures, earthworks, and ceremonial roads must have been highly significant, particularly one formation, which was a circle plus octagon. From its shape and from other images made by the Hopewell, scholars feel confident it represents Grandmother Spider, who is thought to have lived on the plains, and who was broadly venerated as the shamanistic divinity who brought wisdom to the people. She enables people to “see” the light of night and day, and guide them up from the underworld, helping their eyes to become gradually accustomed to light.

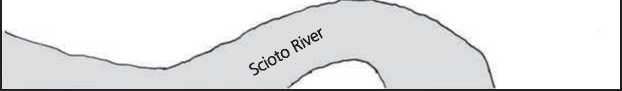

No two earthworks are identical. But that does not mean that there were no common elements. Clearly, geometry was a shared factor, as it had been for thousands of years. But the Hopewell people wanted much more from their mound constructions than had ever been attempted before, as indicated by their intrinsic layouts. At one site, for example, the circumference of the circle matches the length of the perimeter of the square. At another, the diagonal of the square matches the diameter of the circle. At another, the side of an equilateral triangle inscribed in the circle matches the side of the square. Some of the larger circles have radii that conform to the diagonal of a square drawn over smaller circles from other places, perhaps indicating dominant and subservient circles. In all cases the geometrical elements are aimed at communicating to the world beyond, establishing peaceful contact with these higher forces (Figure 6.24a, 6.24b).

Figure 6.22: Hopewell sites In the Scioto River area, Ohio. Source: Mark Jarzombek

I

Figure 6.23a, b, c, d: Ohio mounds: (a) Frankfurt Mound, (b) Mound City, (c) Liberty, (d) Hopeton. Source: Mark Jarzombek/E. G. Squire and E. H. Davis, Ancient Monuments of the Mississippi Valley: Comprising the Results of Extensive Original Surveys and Explorations (Edward O. Jenkins: New York, 1847), 72

IV'

“(Itfflir

Figure 6.24a, b, c: Marietta Works, Ohio: (a) map; (b) reconstructed landscape; (c) site plan. Source: Mark Jarzombek/E. G. Squire and E. H. Davis, Ancient Monuments of the Mississippi Vaiiey: Comprising the Results of Extensive Original Surveys and Explorations (Edward O. Jenkins: New York, 1847), 72

Figure 6.25a, b, c: Octagon at Newark Earthworks, Newark, Ohio: (a) map; (b) site plan; (c) octagon. Source: Mark Jarzombek/E. G. Squire and E. H. Davis, Ancient Monuments of the Mississippi Vaiiey: Comprising the Results of Extensive Original Surveys and Explorations (Edward O. Jenkins: New York, 1847), 66

The earthworks might also have been associated with lunar or solar events. In mythological terms, Grandmother Spider, for example, was responsible for the stars in the sky. She took a web she had spun, laced it with dew, and threw it into the sky, upon which the dew-drops became stars. Possibly, Newark tracked the movements of the moon27 (Figure 6.25).

Much like the mounds of old, the mounds here, too, were composed of layers of different colored sand and earth. One mound in Seip, in particular, was made completely out of red ochre, while the Mound House on the Missouri flood plain was built over a layer of yellow sand that had been imported to the site. Other mounds show that the builders brought yellow clay, light purplish topsoil, brown clay, and gravel by the basketload to assure that a large number of soils of contrasting color and texture were juxtaposed with one another. The dead were ofl:en buried in a particularly black peat or marsh earth. Baehr Mound 2 contains extensive deposits of over flve thousand hornstone implements placed in four layers with a stratum of yellow sand between each layer.28

The charnel houses that were built to house the dead and in which they were cremated give us further information on the tribal architecture, for one can assume that they were modeled on the houses of the living. These houses are rarely square. Instead they tend to be elongated along the diagonal. One researcher, William Romain, thinks that this was because the primary axis of the house was the diagonal and its alignment to the phases of the moon. Once that had been set, the rest of the house was angled together, its overall geometry being not the main spatial consideration. The houses were, nonetheless, meticulously built with staked posts defining their perimeter. They probably had conical thatch roofs. Though the significance of the moon might seem obvious, the Ohio people apparently held that the otherworldly realm was the inverse of the living world. If the sun provided life during the day, the moon was the life-giving force at night. It is likely, therefore, that the squares represent the sky, whereas the circles represent the earth, which according to legend is conceived as a great flat island resting on the water’s surface or suspended from the sky by four cords attached at each of the cardinal directions.29 Romain suggests that these structures are more than just burial and ceremonial sites. They are cosmological diagrams, three-dimensional frameworks if you will, for shamanistic communication between the upper and lower worlds.

Passing to the “other world” was symbolically facilitated by the birds. In the Scioto Hopewell practices, for example, vultures may have been employed to deflesh corpses prior to cremation or bundling for burial. The significance of the vulture is obvious at the North Benton Mound in Ohio, which is a mound 25 meters in diameter. Just inside the outer limits of the earth mound was a wall of stones, enclosing the whole structure. For the most part, boulders of sandstone were used, set on edge and joined end to end. Within this encircling wall were post holes suggesting that a wooden structure or fence had been built. The two lines of post holes running from the opening in the encircling stone wall toward the center appear to be an approach corridor. At the east end of this passage, and approximately in the center of the mound, was a square area, about 4 meters across, that was a hearth. Past the hearth lay the effigy of a vulture with wings spread wide and reaching 10 meters across. It was molded from clay and mounded to a height of about 20 centimeters above the floor. The surface of the vulture was made of slabs of white sandstone. When the structure was finished, it was used for numerous burials, with special burials over each wing of the bird. The southern wing burial was of an extremely large male, lying on his back, with arms and legs extended and head oriented to the west. The burial was completely enclosed in a thick envelope of fine, clean, river sand.30 Eventually the whole thing was mounded over (Figure 6.26a, 6.26b).

World History

World History