Flavian Rome (AD 69-96)

The original and very ambitious building program of the Flavian emperors in Rome has only recently received the attention that it merits, although we know very well-preserved monuments from this period, notably the Colosseum or the arch of Titus on the forum. First of all, numerous reconstructions were imposed by the great fires of AD 69, which heavily damaged the Capitol and the forum Roma-num, and of AD 80, destroying much of the central Campus Martius; both of them authorized the second dynasty to reconstruct in a strong programmatic way the Augustan Urbs. The new Rome of the Flavians, including very innovative constructions, concerned all parts of the Urbs and all types of monuments. Another destruction was of benefit to the Flavian urban reshaping: the full reorganization of the huge area once covered by the domus Aurea, the sumptuous private palace of the emperor Nero, which was almost completely destroyed: the entire space was ‘restored’ to public use (and thus to the Roman People) and included the completion of the unfinished temple of divus Claudius (Figure 9), a gigantic stone amphitheater known as the Colosseum, part of Vespasian’s forum (see below), a monumental thermal complex built under Titus, a ludus for gladiators, a new version of the Meta Sudans (a monumental circular fountain) and finally, important Domitianic extensions of the Palatine imperial residence recently excavated; among these discoveries, there is to mention a monumental terrace-garden built on huge substructions on the northeast side of the hill including an absidated portico, and a new access ramp with an entrance arch to the Palace.

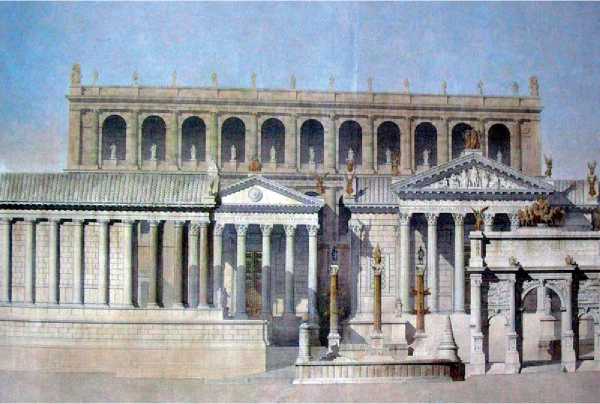

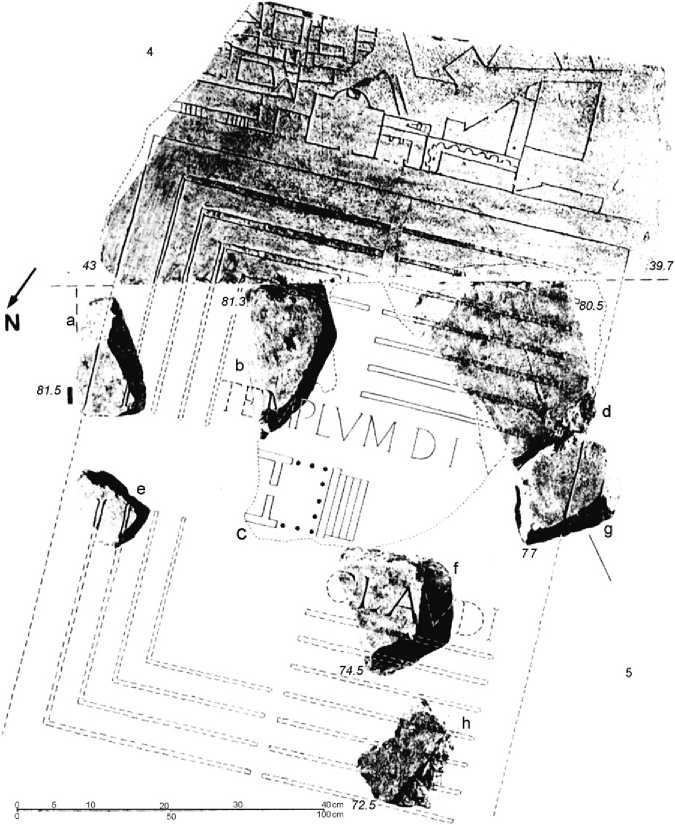

Figure 9 A temple for the imperial cult: the temple of Divus Claudius on the Forma Urbis.

In the traditional political center of the city the Flavian emperors, like Augustus before them, realized minor transformations; there is to mention a systematic scansion of the Via Sacra from the Field of Mars to the Capitol, with arches or commemorative monuments evoking the Flavian victory and the Jewish triumph of AD 70: for instance the arch of Titus in the Circus Maximus, known essentially from epi-graphic evidence, and that of the Velia, fully preserved today.

The Flavian dynasty built or rebuilt no fewer than 50 major public monuments in Rome representing a complete monumental panoply and including two new dynastic temples (see below), a mausoleum temple, two new imperial forums, a stone amphitheatre, and many sanctuaries and honorific monuments. Moreover, recent research has revealed that important cutting and leveling works had already begun under Domitian on the site of the future Trajan’s Forum, which suggests that Domitian had planned the construction of a second imperial complex. The scale of the works begun under Domitian as well as the stylistic characteristics of Domitianic architectural decoration clearly demonstrated for the first time a centralized organization of the urban building ‘industry’ and of the ateliers at an unprecedented level.

The Imperial Forums

The area of the imperial forums is the one that has recently offered most innovative historical perspectives due to the extensive excavations in the city centre realized on occasion of the Roman Jubilee (2000) (Figure 10): the traditional image of these forums formed in the early nineteenth century has been for the first time modified in a radical way, in particular concerning the planimetry of Trajan’s and Augustus’ forums; recent research has also brought new evidence about the successive phases of these monumental programs (some of them only projectual) and about the early mediaeval occupation of the area of forum Transitorium (Figure 11) and Temple of Peace, which results are at present exhibited with axonometric reconstructions in the recent Crypta Balbi Museum. Moreover, a large-scale research project is aiming at studying all the architectural fragments from the forums and the provenience of their material while a new Museum specifically dedicated to the history of the forums is to be opened in Trajan’s markets.

The most important recent findings concern Augustus’ Forum, which included a third semicircular exedra on its south part, Trajan’s Forum, where no monumental temple to divus Traianus has been found, and the central area of the Templum Pacis.

The three first ensembles are those of dynasty founders, Caesar, Augustus and Vespasian; the multifunctional forum Iulium dedicated to Venus Genetrix, divine ancestor of Gens Iulia, associating an axial temple consecrated to a dynastic divinity, a closed colonnaded portico, a rich artworks display as well as administrative, political, or cultural annexes is rightly considered as the prototype of the imperial forums. Caesar’s Forum was symbolically and topographically linked to the Curia Iulia opening on the forum Romanum, the Atrium Libertatis which included the first public library of the capital and the aedes divi Iulii, creating a continuous monumental sequence placed under Caesar’s patronage. Epigraphic evidence from recent excavations regarding Praefecti Urbi attests the continuity of use of this complex until the fourth century AD.

The Temple of Peace was an imperial forum which has provided very scarce archaeological evidence, although ancient sources mention it as one of the most beautiful monuments of the capital in that period. In particular, Pliny the Elder tells about its famous pictures and sculptures from Classic and Hellenistic periods, about sumptuous marbles and fountains. Nevertheless, the complex also housed offices of the Roman administration, libraries, and a hall where a huge marble Map of Rome was to be seen, probably as early as the Flavian era. Although the fragments of this map, dating from a Severan restoration of the site, were first discovered in the sixteenth century, the Forma Urbis nowadays remains the essential primary source for Roman topography studies which focus on the precise localization of the ancient buildings mentioned by textual sources (Figure 9). to the excavations of the ‘millennium year’ our knowledge of the Templum Pacis is more precise (Figure 10): the surrounding portico was elevated on a podium and a central area without stone pavement included a series of parallel longitudinal basins forming canals decorated with rose plantings. Although a series of statue bases inscribed with the names of famous sculptors from the Classical and Hellenistic periods was found during ancient and recent excavations, the original location of the statues in the monument remains uncertain.

The second Flavian Forum, that of Domitian, was, like its predecessor, a victory monument dedicated to Minerva, the patron goddess of the emperor, whose temple dominated the complex. Ancient sources mention it as forum Transitorium because of its position between forum Augustum and forum Pacis, that conditioned its particular architectural aspect, including a ‘false’ and deluding portico along the side walls (Figure 11). The continuous frieze of the portico included a representation of the myth of Arachne linked to Minerva and the attic was adorned with a series of standing female figures in relief which are very

Figure 10 Map of the imperial forums including recent discoveries.

Figure 11 The imperial forums: the forum of Nerva and the so-called ‘Colonacce’.

Likely personifications of the Provinces of Empire announcing the figurative program of the Hadria-neum. The triumphal vocation of this Forum remained since Alexander Severus erected the bronze statues of Roman triumphatores.

Trajan’s Forum was the latest and most impressive of the imperial forums. The intervention of the dama-sian architect Apollodorus could explain innovative aspects of the complex; like other forums, Trajan’s Forum was a multifunctional ensemble commemorating the princeps’ triumph over the Dacians (present Romania). The most famous feature of this Forum is obviously the Trajan’s Column, high 40 m., providing a continuous sequence of historical reliefs narrating the imperial campaigns and victory. Moreover, this column showed the height of the excavations occasioned by the construction of the complex; finally, it became the tomb of the emperor Trajan. The monument was surrounded by two libraries which recent research has proved to be two-storeyed buildings. But the complex was dominated by a huge apsidal basilica whose attica received colossal statues of Dacian barbarians carved in Egyptian green marble and porphyry and giant Medusa medallions.

The basilica opened on a large square decorated with great reliefs presenting the same subject matter as those of the column in a more synthetic visual language: some of the panels of this ‘Great Trajanic frieze’ have been reused as spolia (‘loots’) in the arch of Constantine. Finally, a colossal equestrian statue of the Emperor stood in the square: recent excavations gave its precise location, not in the center but in the southwest part of it. A key problem of the topography of the Forum is the location of the temple of Divus Traianus mentioned by textual sources: although the absence of a temple under the Palazzo della Provincia, already noticed during excavations made at the end of the nineteenth century, has been proved definitively, no element of a monumental structure has been discovered elsewhere; nonetheless, recent works have brought to light decisive evidence concerning the entrances to the forum: its south delimitation wall was not rectilinear, but segmented, while the north access included a monumental pronaos (‘vestibule’).

It is important to outline the extraordinary durability of these ensembles still in use in early medieval times: late antique restorations or reconstructions are attested for the major part of them.

Glory and Cult of the New Gods: The Monuments of the Imperial Cult

The constitution of the aedes divi Iulii, the altar dedicated to the deified Caesar and consecrated by Augustus in the place of Caesar’s funerary pyre, whose remains are still visible on the forum, initiated the long series of monuments designed for the cult of the new gods of the Roman State; its prominent location, in the vicinity of Caesar’s Forum and in front of the Capitoline Hill, reveals the importance immediately conferred to this cult and marks the beginning of the annexation of the political centre by monuments erected to the glory of the imperial family. Over a range of two centuries, from Augustus to the end of the Antonine dynasty (98-192), the literary and archaeological sources attest no fewer than 11 new temple foundations. The two nodal and attractive monuments which conditioned ulterior constructions are Augustus’ Mausoleum on Campus Martius on the one hand and the aedes divi luli on the forum on the other hand. The Field of Mars, traditionally dedicated to the expression of the posthumous glory of prominent Romans, was a natural place for imperial funerals led in monumental ustrina which soon became permanent installations. The first imperial temple erected in this area was the so-called porticus divorum dedicated to the deified Vespasian and Titus; but the major development of imperial cult was due to the Antonine dynasty with the construction of an impressive series of honorific and cultic monuments that radically transformed the cityscape: a new dynastic Mausoleum by Hadrian (present-day Castel Sant’ Angelo (Figure 1)), a temple to divus Hadrianus, still preserved on actual Piazza di Pietra, a basilica to Faustina and Plotina nowadays completely destroyed, a commemorative column to Marcus Aurelius replicating Trajan’s column today visible in Piazza Colonna, another complex including an ustrinum, an ara and a column to Antoninus Pius, which pediment depicts the ‘apotheosis’ of Antoninus and Faustina, and finally, a temple to Marcus Aurelius and Faustina.

Nonetheless, the Ancient Forum preserved its attractive force since each important dynasty erected there at least one temple: we can mention that of the deified Vespasian, facing the aedes divi luli, and that of Antoninus and Faustina along the Sacra Via. Finally, several of these monuments have an eccentric location because they were erected on birthplace or familial residences of the emperors: the Templum Gentis Flaviae has replaced a Flavian domus identified, thanks to a fistula inscribed with the name of T. Flavius Sabinus, a sacrarium was dedicated to divus Augustus on the Palatine Hill, and the location of the Templum divi Claudi on the Caelian hill (Figure 9) is probably related to the mythical history of the Claudii.

Besides the monumental temple foundations, a large panoply of minor monuments were directly related to imperial religion and ideology; so the altars dedicated to the genius of the emperor, the Lares

Augusti or the imperial virtues (Providentia, Pax), and also the numerous historical scenes which decorated honorific monuments. These monuments were recently objects of a renewed attention although they are mostly without topographical context.

These dynastic temples have particular importance for the story of the sanctuaries of Rome because they represent the only new religious foundations of the imperial period after the Flavians; Republican and Augustan temples were continuously restored and rebuilt by the emperors, sometimes with consequent transformations of the original form of the monument (so Hadrian’s Pantheon, whose main architectural feature was the entirely conserved cupola, although reproducing on the fac:ade the original dedication by Agrippa, was a real re-creation by the new emperor and included the addition of a monumental portico, the basilica Neptuni). On the one hand, a form of saturation of the urban space limited the opportunities for new constructions. On the other hand, for religious, cultural, and ideological reasons, the cityscape of Imperial Rome was characterized by a strong conservatism: besides the impossibility to modify the location of the sanctuaries, the pietas manifested by the successive emperors toward the monuments built by prestigious predecessors was another important factor in the stagnation of the large-scale building projects in the second century AD. From Trajan onward, most of the imperial dedications were dynastic monuments or restorations.

The Spectacle Monuments

First of all, the ludi (public games) represented an essential part of the celebration of Roman cults and especially of the major festivals held in honor of the gods; since they were strictly related with a specific deity and, consequently, with a sanctuary, they generally took place in the vicinity of it, in the forecourt of a temple or in an adjacent square. This situation contributes to explain the fact that the Urbs remained for centuries a city with no permanent spectacle monuments in stone: the games generally took place in wooden temporary constructions (which left no archaeological remains) or in monuments originally designed for other functions. So a multiplicity of places and buildings could be used for gladiatorial or scenic performances: before the construction of the first permanent amphitheater of the capital in the second half of the first century BC, the munera were given on the forum Romanum, where subterranean service galleries have been discovered under the paving of the place, in the Saepta on the Campus Martius, or in the ancient Tarentum that comprised an area for chariot racing.

The nonspecificity or the pluri-functionality of public buildings is a major feature of Roman architecture.

In this context, the Circus Maximus, located between the Aventine and Palatine hills, represents a notable exception both for its chronology (it is the most ancient spectacle monument of Rome, since its construction is traditionally linked with the Etruscan kings) and for its monumentality: in the second century AD, it could accommodate 150 000 spectators. Although various works are attested for the Republican period, major transformations were due to Agrippa and Augustus: the Circus received new marble installations and decorations on the central platform, and an imperial tribune was built, while not until the beginning of the second century AD the process of monumentalization was fully completed.

The end of the first century BC marks an essential turning point in the story of the spectacle monuments of Rome: in a space of less than 50 years, three stone theaters were built, all of them concentrated on Campus Martius: the theaters of Pompey (see above), of Marcellus, and of Balbus. The second one, which is better preserved today than the first one because of its transformation into a fortress and a palace in medieval and modern times, was designed for the ludi Saeculares of 17 BC and dedicated by Augustus to his deceased nephew Marcellus. Finally, the theater of Balbus, associated to a monumental portico and a Crypta, was built in the same years to commemorate the victory over the Garamantes: only the subterranean part of the portico is well preserved. These monuments, functional to a new typology of games and spectacles, were also victory monuments perpetuating the tradition of the great porticated places and temples dedicated by the Republican triumphators in the Hellenistic style but at the same time they offered a new monumental frame as well as new opportunities for the expression of personal - and soon for imperial - propaganda. Moreover, new regulations concerning the distribution of spectators in the semicircular cavea mirrored the hierarchy of the Augustan society.

The construction by Vespasian of the Amphithea-trum Flavium, best known as the Colosseum, as a manubial monument after the Jewish triumph of AD 71 marks a new step in the history of spectacles in Rome: the ideological signification of this huge monument of a new type - the restitution to the populus Romanus of a place unjustly privatized by Nero’s domus aurea (Golden House) - was reinforced by a prominent location in the heart of Rome, in the immediate vicinity of the forum Romanum (foro prox-imum), unlike the first stone amphitheatre of the capital, built in 29 BC by T. Statilius Taurus on Campus Martius and destroyed in the great fire of AD 64;

The capacity without precedence of the amphitheater reflects a new conception of relations between emperor and Roman people, as well as a substantial change of taste of the public, since gladiatorial spectacles had to replace scenic and musical performances. Moreover, a monumental stone ludus for gladiatorial training was part of the building program. The first permanent stone amphitheater of the capital soon became the highest symbol of Rome’s power, grandeur, and eternity. During Mussolinian excavations was discovered the huge pedestal of the colossal statue of Nero-Sun God, which gave its name to the monument, as well as the remains of the Meta Sudans, a monumental fountain built by Augustus; all of these structures were demolished for the realization of the actual Via dei Fori imperiali. Most recently, new investigations have completed our knowledge of the history of the Colosseum valley prior to the construction of the amphitheatre, revealing the existence of monumental Neronian porticoes in connection with the Velia and a religious complex including a temple restored by Claudius and a shrine for the imperial cult adorned with statue bases of members of the Julio-Claudian family. These radical transformations in urban landscape in the heart of the city in a space of one century reveal the rapidity of social, ideological, and political changes related to imperial politics and constitute a good example of the extreme complexity of the stratigraphy in a city like Rome.

The fire of AD 80 which damaged a large part of Campus Martius gave to the new emperor Domitian the opportunity for an important transformation of the area; not only did he restore Pompey’s theatre, the Iseum Campense or the Porticus Minucia in the area of Largo Argentina, but he also introduced new monumental spectacle buildings, two of them being without precedent in Rome: an odeum and a stadium designed for the celebration of Domitianic music, poetry and game festivals dedicated to Jupiter, which is the only example of this type of building actually known for the western part of the empire. The actual Piazza Navona still preserves the shape of the ancient stadium that exemplifies the introduction by Domitian in Rome of games and spectacle monuments typical for Greek culture. A restoration of the monument by Severus Alexander in the late third century AD shows the long-lasting imprint of this monument in the city. Nonetheless, because of the nature of the archaeological remains, we possess more documentation about the architecture of spectacle buildings - and thus about permanent structures than about the spectacles themselves and the temporary installations related to them.

World History

World History