On discovery of buried human remains the area becomes a scene of crime. It will be cordoned off, a common approach path will be identified, and a scene-of-crime team deployed under the auspices of a Crime Scene Manager in order to recover the evidence. Unlike an archaeological site, the crime scene can include both the immediate surface environment of the grave as well as the grave itself. No attempt to investigate the grave will be undertaken until the adjacent ground surface and associated features have been fully recorded by video and photography, and the ground surface subjected to fingertip search. The manner in which the grave may have been concealed, the presence of footprints or tire-marks, and local vegetation may all need to be taken into account before any archaeological activity can take place. Only critical personnel will be permitted into the cordoned area, each will be logged in and out by a uniformed officer, and all will be required to wear special disposable clothing, sometimes known as ‘whites’. These are to prevent the scene being contaminated or confused by material from the clothes of the investigating personnel and include disposable overshoes, hoods and rubber gloves. Masks are intended to minimize the spread of DNA. New tools are invariably used for each scene (including spades and trowels, etc.) in order to prevent cross-contamination from other scenes. At most the key team is likely to consist of the forensic pathologist, one or two scene-of-crime officers (one of whom may act as photographer), an exhibits officer, and an archaeologist (if invited). In some instances where hard tissue is concerned, a physical anthropologist may also be included. Physical anthropologists are now becoming increasingly involved in medicolegal matters, especially at postmortems. There may be a briefing first so that all concerned are agreed on a common strategy, and the pathologist is likely to be the lead figure as he/she will be required to give evidence in court on the cause and manner of death.

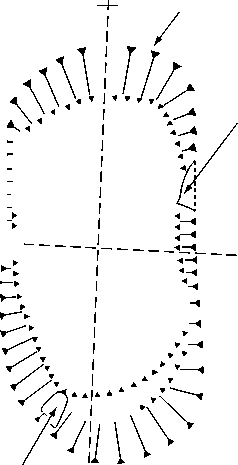

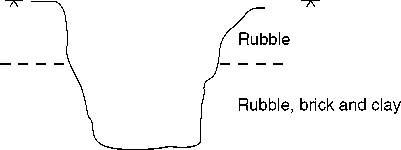

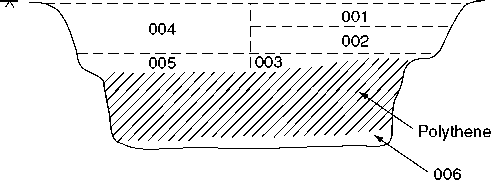

Subject to agreement with the pathologist, excavation is normally geared in the first instance to identifying the grave outline, determining stratigraphic relationships between the grave fill and the surrounding ground, and setting up a recording regime. Fixed points need to be identified and plans produced, although these can now usually be carried out (if requested) by traffic officers using an electron distance measure (EDM). In most circumstances, however, in confined areas plans are more easily and rapidly produced by hand. In most, but not all, cases it may preferable to half-section the grave in order to identify any particular pattern of infill in the exposed section. The section might, for example, show that a grave had been carefully backfilled with specific materials in order to minimize discovery. This might be used to demonstrate in court that the perpetrator was in a sound state of mind in disposing of the body, with resultant implications for motive and outcome. Most grave fills, however, are simple mixes of backfilled substrates and require excavating in numbered ‘spits’ with spoil usually retained in sealed containers such as large plastic dustbins for later sieving. Any exhibits recovered are ‘seized’ by the exhibits officer who will log, number, and bag them and thus commence a chain of custody that will retain the legal integrity of each exhibit until such time that it is required in court. Graves often contain items deliberately concealed by the perpetrator, for example, soiled clothes or a weapon, as well as items conveniently discarded such as cigarette butts or datable newspaper.

Forensic recovery is no different from any other type of archaeology in being destructive and therefore requiring the practitioner to excavate according to a research design in order to answer specific questions. Unlike ‘traditional’ archaeology, however, these types of questions tend to pertain to an individual event. The interrogation might consider how the grave was dug, what tools were used, whether it was excavated in a hurry or had been carefully prepared or even left open, whether it contained an unusual fill or any foreign material, or whether it contained material transferred from the offender into the fill. These and similar questions culminate in the overarching question ‘who killed this individual?’

This type of evidence needs to be looked for and recovered as a matter of priority even if it entails excavating in unusual or unorthodox ways. Equally, the victim needs to be uncovered and removed in a manner that will retain any forensic evidence on the body itself, avoid contamination from nongrave contexts, and prevent additional trauma to the body itself. This often has to be undertaken in confined, screened, or tented areas, sometimes in cellars or narrow gardens, and this can present practical difficulties which have to be surmounted ‘on the hoof’. Space permitting, access to the body may need to be facilitated by digging out a platform from the side of the grave in order that work on the body can take place at the same level. No matter how the job is done, at the end of the day the archaeologist needs to be able to recover essential data according to the highest possible standards in order for it to be presented in court and defended under cross-examination. Often this will need ingenuity and inventiveness, especially if a suspect is being held in custody with specific time constraints under the terms of the UK Police and Criminal Evidence Act 1984. Irrespective of physical constraints, it is essential to produce basic archaeological records in written and graphic terms (Figure 2).

Throughout this process, the archaeologist will still need to be aware of other forms of evidence, including any necessary sampling for entomological or environmental purpose, and will be mindful of the limitations of his or her own expertise, and acknowledge when further specialist support is necessary. Records will need to be made in the normal way but, unlike normal archaeological records, they will be subject to disclosure, that is, they will need to be made available to the court, including defense counsel. This includes all written and photographic records, all plans, notes, context sheets, and any dictaphone tapes and is necessary under the terms of the UK Criminal Procedure and Investigations Act 1996. This is a useful reminder that the forensic archaeologist is a witness of the court, not of the commissioning party, and has an obligation to present objective evidence irrespective as to whether he or she is representing the prosecution (the Crown Prosecution Service) or the defense. In this, and other respects, much of the work of the forensic archaeologist differs from that of the more traditional

Figure 2 Standard record of grave, including profile and showing recovery of grave fill in numbered ‘spits’. © 2008 Professor John Hunter. Published by Elsevier Inc. All rights reserved.

Archaeologist and may require different skills and experience. Levels of competency in this area have been defined by the Council for the Registration of Forensic Practitioners (CRFP).

World History

World History

![United States Army in WWII - Europe - The Ardennes Battle of the Bulge [Illustrated Edition]](https://www.worldhistory.biz/uploads/posts/2015-05/1432563079_1428528748_0034497d_medium.jpeg)