Some of the issues raised above are revisited through one example from the Kalinga Ethnoarchaeological Project (KEP). This project is directed by William Longacre at the University of Arizona, who began studying contemporary potters in 1973. His choice of potters in Kalinga Province, the Philippines, was influenced heavily by a colleague, Edward Dozier, whose ethnographic fieldwork in the region indicated that ceramic vessels were still made and used within Kalinga households. Over the past 30 years, Long-acre’s initial research focus on pottery decoration has expanded into broader investigations of household ceramic manufacture, use, and exchange. Longacre continued to collect data himself for decades and directed one large field season during the 1987-88 academic year. Many of his former students, including Michael Graves, James Skibo, and Miriam Stark, have also published their work with this project.

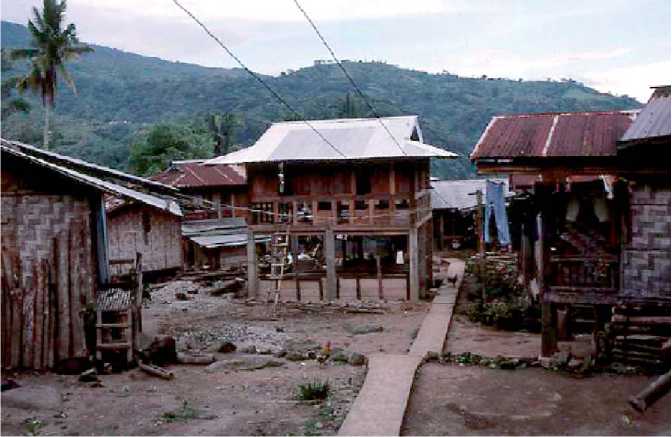

The KEP is based in the Pasil Municipality along the Pasil River Valley in northern Luzon, the Philippines. The study area has two things in common with many other ethnoarchaeological field locations. First, most people in Pasil are farmers who grow Almost all of their food and have limited access to cash. Second, the area is relatively inaccessible due to the local topography. The Pasil villages are located on mountain slopes (Figure 1), and unpaved roads reach some but not all of them. Electricity is only

Figure 1 View from Dalupa across the Pasil River Valley towards two nearby communities.

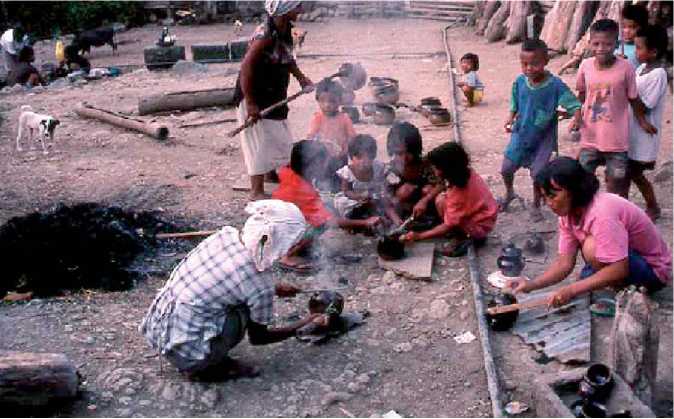

Available from gasoline-powered generators; it is used primarily for powering lights at night, and even then not consistently. Fewer commercial goods reach these communities because they are difficult to transport and also difficult to afford. Ceramic cooking vessels stay in use longer in these settings, perhaps in part because they are locally available and cheaper than the metal vessels that have replaced them in most of the world (Figure 2).

The example used here is drawn from the 2001 field season in Dalupa (Figure 3), a community of 380 people in 71 households. As a prehistoric ceramic analyst, the author was especially interested in ceramics from middens, or trash dumps, because archaeologists recover large samples of ceramics from these contexts. Many more vessels are broken and discarded into middens than are left in other contexts, such as within houses during abandonment. During our fieldwork, we tracked the movement of discarded vessels into middens to link refuse deposits with their source areas, such as households or groups of households, and to see how well midden assemblages represented what was thrown away.

Households are the focus of much anthropological and archaeological inquiry. Relying on observed ethnographic and ethnoarchaeological patterns, archaeologists have tried to associate attributes of household ceramic assemblages or social groups with household size and composition, wealth or status, social obligations, and diet, cuisine, and food preparation techniques. To draw these connections, however, they need to isolate the ceramics from different households or groups of households. Our goal was to see whether, using the right approaches, they could include midden ceramics in such studies.

Methods

The choice of methods is crucial in an ethnoarchaeo-logical study, particularly if the authors claim to find a broader pattern that applies to other situations. Archaeologists need to have confidence in the results before using them in archaeological interpretation, and should ask some pointed questions. How exactly did the ethnoarchaeologists document their patterns? How much variation might be expected from these patterns? Could any of the data sources be biased, and how and why? The best way to show the crosscultural applicability of a pattern is often to look at as many cases as possible, but authors can at least increase confidence in their particular case through careful data collection. David and Kramer provide an excellent overview of fieldwork methods and concerns unique to ethnoarchaeology. KEP fieldwork here is offered as one concrete example of ethnoarchaeological methods.

Figure 2 Local potters in Dalupa apply resin to ceramic pots after firing to waterproof them.

Figure 3 View down the central thoroughfare (cement sidewalk) of Dalupa. Because of Dalupa’s location on the side of a mountain, houses sit on residential terraces with stone walls like the one visible in the foreground.

Matthew Hill and Margaret E. Beck spent five months living in Dalupa and conducting fieldwork. They relied partially on interviews with Dalupa residents and partially on their independent observations of behavior and physical deposits, collecting data from household ceramic inventories, weekly questionnaires, and physical investigations of middens and artifacts.

The interviews were conducted in English with the help of four local assistants, who translated as necessary. While use of English is widespread in the region, the dominant language is Kalinga. Interviews are a relatively quick way to get information on a variety of topics, and may be the only way to get some kinds of data. Some responses may be inaccurate or misleading, however, as informants may not remember events in sufficient detail or may adjust answers in attempts to please interviewers or avoid embarrassment. We attempted to reduce informant error by interviewing households once a week and collecting data over the entire field season, asking informants only to remember very recent events. We also reviewed questionnaire data for internal consistency and field-checked data whenever possible. Rosemary Firth describes and illustrates well the value of crosschecking interview data in Housekeeping Among Malay Peasants.

We visited each house at the beginning of fieldwork to record all of the ceramic vessels owned by each family. Toward the end of the field season, we visited everyone again and re-inventoried their ceramic vessels. We compared the totals and then asked the family about any discrepancies, including vessels they may have broken or discarded.

One of our local assistants visited every family once a week to ask about cooking vessel use, general household discard, and ceramic breakage and discard. First, people were asked what their family had cooked the previous day and which pots they used to cook in. They were also asked what they threw away the previous day, and where they put it. Finally, they were asked if they had broken or otherwise damaged any ceramic vessels during the week, and what they did with the vessels afterward. Their reports of damage from weekly interviews should have been consistent with the final ceramic inventories, and families were asked about any discrepancies during the final vessel inventories.

We mapped the entire village, including any visible accumulations of trash. Each accumulation got an arbitrary number. Every week we reviewed the questionnaire data and matched the reported discard locations to our mapped trash piles, checking for new trash piles as needed. In this way we estimated how many households, and which households, threw trash into a particular midden.

Once the middens were defined, we documented them in more detail. We mapped them in plan view (Figure 4), cored them along a center line to determine depth, and recorded the items present on the surface in sample units. We also excavated test units in two active middens. We collected 3001 midden sherds, including surface sherds from 17 active middens and excavated sherds from two middens.

Results: Trash and Trash Accumulation

Most trash within the Dalupa residential area is produced by household activities. Household trash generally consists of household items and waste from routine activities, such as meal preparation and personal hygiene. It is usually temporarily collected in a container within the house, such as a large metal can, that is periodically carried outside and emptied. Ceramic vessels are thrown away close to where they were broken, in most (79%) cases within 10m. Ceramic vessels broken within houses were treated like other household trash, although as relatively large objects, they might be thrown away immediately rather than placed in the trash can.

One major difference in household trash between Dalupa and communities in the United States is that leftover food is almost never thrown away. It is instead shared with other people or given to domestic animals, and does not find its way into middens. Some inedible (to humans) by-products of food processing, such as pea pods, are thrown away.

Discarded items do not accumulate randomly all over the village. The piles of trash often smell, attract insects and scavenging animals, and occupy space that could be used for other activities. Residents therefore come to some informal agreement about where trash may accumulate, and it becomes concentrated in certain locations as middens, known as aggil in the Kalinga language. In Dalupa and in other ethnoarchaeological settings, middens tend to appear in or along streams or washes, around the edges of house lots, and off the sides of hills or terraces.

Figure 4 This midden belowa terrace wall was photographed just before mapping. (The line through the midden center is a measuring tape.) Note the spectators along the wall. Especially in the beginning of the field season, most of our activities gathered a crowd.

There were 32 active middens in Dalupa during our fieldwork, covering about 10% of the residential area. Dalupa households use between one and three middens for disposal of their daily household waste, although they tend to concentrate their refuse in one midden closest to their house.

Some middens are used by a particular house and others are shared by multiple households. We grouped middens into three categories based on household contributions: household (used by only one household), local (used by two to five households), and communal (used by six or more households). Household and local midden users transported their refuse relatively short distances, averaging 6 and 11m, respectively, because these middens were either within or adjacent to their house lots. The communal middens shared by many more families tended to be farther away from their houses, and communal midden users transported their trash nearly 35 m from their households On average.

People apparently prefer to put a household midden close by, within their own house lot, when they have the space to do so. Household middens are found among the Maya households in the Coxoh Project area and in Philip Arnold’s sample of Mexican households in the Sierra de los Tuxtlas, Veracruz. The average house lot size in the Veracruz sample is 282 m2. In Dalupa, where house lots average only 156 m2, residents are often forced to share middens with their neighbors.

Middens in Dalupa are constantly disturbed even while they are forming. Younger children have not yet been fully socialized to avoid the trash, and often play in middens and collect materials from them.

Domestic animals such as pigs, dogs, and chickens scavenge for food and also enter the middens to consume rice chaff, banana peels, and other discarded organic materials (Figure 5). Because middens are often very close to living and working areas, they received significant foot traffic in some areas and might be shifted or disturbed by outside cleaning activities. For example, neighbors occasionally moved small middens away from their house if the smell or waste bothered them; larger middens near public spaces, such as the basketball court or elementary school, were pushed back or burned, or both, to clean up the area before intra - or intercommunity events (Figure 6). The movement, cleaning, and trampling of middens reduces many items to plastic, metal, glass, fabric, and ceramic scraps. Faunal bone fragments only appear occasionally; in Dalupa as elsewhere, dogs destroy most of the bone produced by butchery and meat consumption.

We argue that the basic rules of trash disposal and midden placement might apply in other settings, allowing archaeologists to link middens to the living and working areas where trash was produced. It would be easier to connect household and local middens with their sources, because they receive trash from fewer households. Those households are immediately adjacent to the midden and can be identified. Household and local middens are visibly different from communal middens, at least in Dalupa, in their smaller size and placement around or between houses rather than around public activity areas. To apply our patterns, archaeologists would need to determine which structures in their site are habitation structures and which structures are contemporaneous.

Figure 5 Animals rummage through a Dalupa midden for food.

Figure 6 The midden adjacent to the elementary school (the building to the right) is burned before the start of fall classes.

We also conclude that middens are good contexts for sampling household ceramic assemblages. Most (73%) discarded vessels went to middens, according to the weekly interviews, although some vessels were left outside the residential area or as isolated artifacts within the village. Both the weekly interviews and analysis of the midden ceramics suggest that the distribution of vessel types in middens is similar to the overall distribution of discarded vessel types.

Discussion In the absence of ethnoarchaeology, data on this topic may never have been collected. Other anthropologists do not seem to want such detailed information about trash and trash dumps, and the limited comparative data available were collected by other ethnoarchaeologists. We also reaped the benefits of a long-term ethnoarchaeological project, as our work was greatly improved by the availability of previous KEP vessel collections and data. For example, we were able to compare the frequency of vessel breakage and rates of ceramic use between the 1987-88 and the 2001 field seasons. Unfortunately, from the perspective of ceramic ethnoarchaeology, we found that ceramic use and ownership significantly declined over this 13-year period.

Ethnoarchaeological fieldwork is similar to other ethnographic research in some ways, but methods reflect (or should reflect) the emphasis on material culture and the need for data comparable to archaeological data. Even so, there are often fundamental differences in the units of observation between eth-noarchaeology and archaeology, as noted by researchers who have worked in both settings, such as James Skibo and Philip Arnold. Moving back and forth between ethnoarchaeological and archaeological perspectives should enhance both kinds of research. We attempted to collect data as comparable to archaeological data as possible, having previously worked as archaeologists and attempted to apply ethnoarchaeo-logical findings to our archaeological data. Only our archaeological audience can judge whether we were successful in our own data collection strategies.

Our goal was to generalize about waste disposal in a village setting, and we suggest the observed patterns should apply in other villages (prehistoric or otherwise) similar to our ethnoarchaeological case. If they do, then midden deposits can be used to compare the material culture between households or groups of households. Archaeologists interested in household archaeology currently rely on material from house floors, which produce much smaller samples. We believe, as do other archaeologists influenced by the New Archaeology, that our generalizations would be refined and strengthened by additional cross-cultural comparisons.

World History

World History