Northeast British Columbia and Alberta

On the east side of the Rockies near Fort St. John, the earliest signs of Palaeoindians are at Charlie Lake Cave in a Palaeoindian level dating about 10 500 years ago, with lanceolate, fluted spear points and square-stemmed Cody-Alberta points (Figure 1). They were found on the surface and likely diffused from the contiguous Plains. At Charlie Lake cave and the Farrell site, 5000-6000-year-old stemmed and notched points precede 2900-2500 year-old points suggestive of the Oxbow type on the Plains, followed by smaller post-1500 year-old notched arrowheads. In northeastern British Columbia, the pre-1830 Beaver people hunted bison on the Peace River prairie and woodland zones, and moose, woodland caribou, sheep and goats in the hills.

The oldest artifacts in northern Alberta may be macroblades similar to Clovis culture specimens found farther south. Later lanceolate points resembling

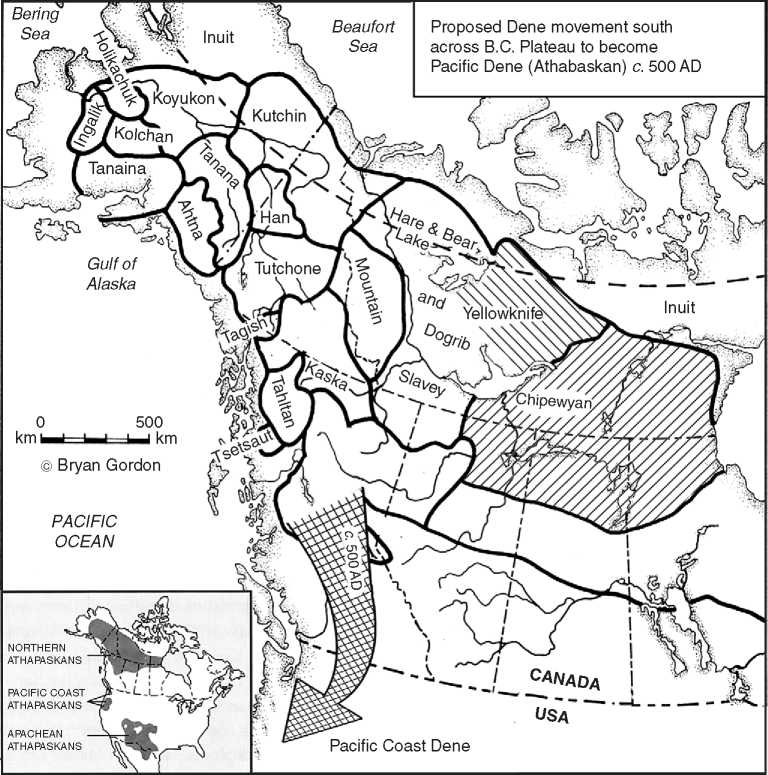

Figure 6 Proposed Dene movement South across the British Columbia Plateau to become the Pacific Dene (Athabaskan) c. AD 500. © 2008 Bryan Gordon. Published by Elsevier Inc. All rights reserved.

The Agate Basin Northern Plano and Hell Gap points of the northern Plains were found on the surface of the Gardiner Narrows and Beaver River Quarry sites, as was an Alberta-Scottsbluff point found near Fort Mackay south of Lake Athabasca (Figure 1). All date about 10 000 years ago on the Plains, but are probably much younger in northern Alberta. A notched burin (see Glossary) and spalls from burin sharpening, microblades and cores came from the 4000 year-old Bezya site, while a microcore came from near Fort Vermillion (Figure 5). These may show ties to the southwest Yukon’s Little Arm phase and to the southwest Mackenzie District’s Pointed Mountain site. The Middle Prehistoric phase along the southern forest fringe includes 5500-2500 year-old notched Oxbow points, representing diffusion, trade or actual Plains people. The Eaglenest Portage site has stemmed and notched points, some being Middle Prehistoric projectiles, others Late Taltheilei arrowheads. The Gardiner

Narrows and Satsi sites, with 3500-2700 year-old Arctic Small Tool tradition points, demonstrate that their Inuit-like bearers came quite far south and even adapted to game other than tundra caribou. Gardiner Narrows and Satsi are not that far from the Karpinsky site, where all Taltheilei phases are represented.

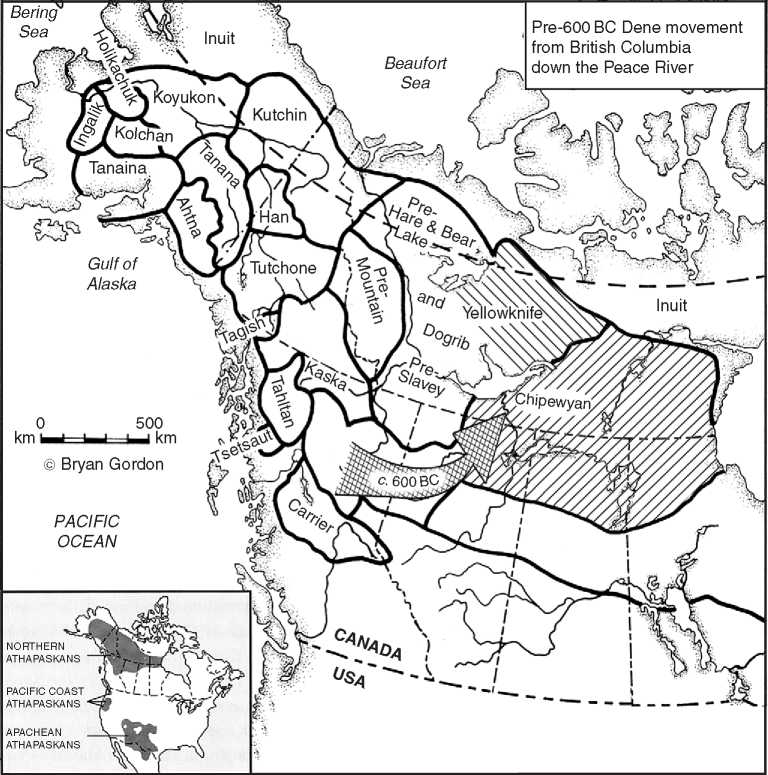

The Taltheilei tradition originated in northern British Columbia from a Yukon Na-Dene tradition and went east via the Peace River to Alberta (Figure 7). This is the only viable portal through the Rockies for groups larger than small, scattered mountain bands and is in the right location for these events. The presence of large sites, like Peace Point on the Peace River gives credence to the importance of waterways to human movement. Unfortunately, most sites have been buried or washed away, although a number of Albertan sites point to derivation from the west by way of the Peace River drainage. A precursor to 2450-2600 year-old narrow, thick, Earliest Taltheilei lanceheads has not been found on the Peace River, but one thin, wide, shouldered point found in British Columbia in the late nineteenth century by Morice resembles Early Taltheilei points. Perhaps looking for Taltheilei origins in the earlier Taye Lake phase in the Yukon is logical because both Taltheilei and Taye Lake have similar overall toolkits, with the exception that side-notched points (in Taye Lake) are absent in Early Taltheilei. And there are the Taltheilei-like points mentioned earlier on the Northwest Coast and Interior of British Columbia. More survey is needed (Figure 7).

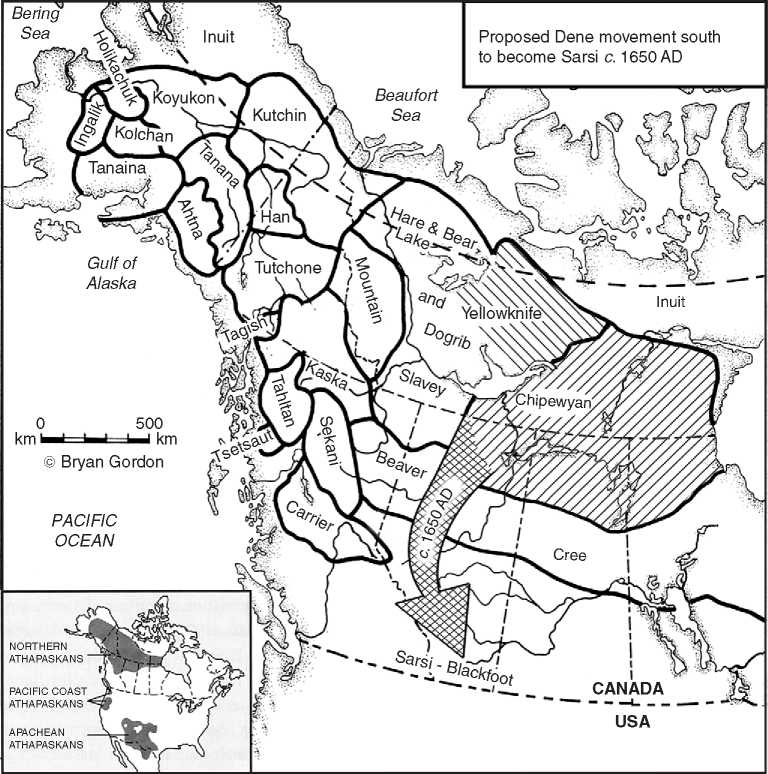

The Karpinsky site in western Alberta is pivotal in tying Taltheilei origin to the Peace River and British Columbia. Judging from the form and non-parallel flaking of unprovenanced Early and Middle lance-heads, it has points of all phases, suggesting the Peace River was a regularly used route. The heavily surveyed northern Alberta Oil Sands have 1000 sites, but none is well stratified and few are radiocarbon-dated. The fact that some points resemble those of Late or Middle Taltheilei and also resemble points found farther south in the Alberta foothills has been the basis of a postulated Rockies foothills route of the Yukon Dene to the American Southwest. A protohistoric foothills migration by Dene hunters is better documented, when Dene left western Lake Athabasca through Beaver territory to cross the far Northwest Plains along the Rockies foothills to become the Sarsi (Figure 8). Indeed, Sarsi and Beaver are close relatives, sharing oral traditions even after Sarsi became Plains hunters. Early historic Sarsi took advantage of annual bison migrations, following them south to amalgamate with and finally dissolve in the dominant southwest Alberta Blackfoot (Figure 8).

A pre-1650 location for Sekani was just north of the Sarsi on the Alberta Plains, while Carrier and

Figure 7 Pre-600BC Dene movement from British Columbia down the Peace River to the Barrenlands. © 2008 Bryan Gordon. Published by Elsevier Inc. All rights reserved.

Figure 8 Proposed Dene movement South to become the Sarsi c. AD 1650. © 2008 Bryan Gordon. Published by Elsevier Inc. All rights reserved.

Sarsi were adjacent to one another east-west, a condition requiring the Beaver to be farther east than at present. Linguistic data show southern disruption of Sekani and Sarsi, who share enough traits to indicate extensive earlier contact, something they have in common with the Carrier. Evidence also exists for the Sekani being farther east, later to be forced up the Peace River from the Alberta Plains by the Cree. If the Sarsi, on their movement south, carried the chitho or hide abrader, it disappeared or changed completely because it is absent in the Old Women’s phase of Alberta.

Northwest Territories-Western Mackenzie District

East of the Yukon and British Columbia, microblade technology occurs only in the late Northwest Microblade tradition and is often associated with flake burins (made by spalling the edge of a flake). Mackenzie Valley and Great Bear Lake microblade assemblages are variants of earlier Alaskan and

Yukon cultures. Simultaneous to the Middle Shield Archaic in the Beverly range of the Thelon River, the 5000-3500 year-old Great Bear River and Franklin Tanks sites near Great Bear Lake have lanceheads, knives, choppers, endscrapers, and microblades mixed with an Arctic Small Tool burin. The nearby NT Docks site has a bladelike assemblage related to the lower level of the Whirl Lake site and dating about 5000 years ago (Figure 5). The lower level at Whirl Lake shows more southern as well as Alaskan and Yukon influence. It and the NT Docks, Pointed Mountain, and Bezya (Alberta) sites all could be defined as 4000-5000 year-old Northwest Microblade variants. But in all assemblages, composition is inconsistent; some have microcores, others have stemmed, notched, and leafshaped points under possible Plains influence. The Great Bear Lake Taltheilei people made lance and arrow heads like those in the Eastern Mackenzie District, plus scrapers, knives, adzes, whetstones, drills and small native copper awls, and knives. Bone, wood, antler, hide, and fur items have not survived the acid soil. Permanent White contact was established when the Hudson’s Bay Company built Fort McPherson on the lower Peel River in 1840, followed two years later by La Pierre House on the Yukon’s Bell River and seven years later by Fort Yukon at the junction of the Porcupine and Yukon Rivers.

The reputed co-occurrence of notched points, burins and microblades continues to obscure the definition of the Northwest Microblade tradition. The Pointed Mountain site has Taye Lake burins, plus microblades; other sites do not. Tenuous ties have been drawn across the Continental Divide between the 1500-2300 year-old Mackenzie complex and late Taye Lake-early Aishihik point types, notched end-scrapers and burins. The 1400 year-old Fish Lake complex retains side-notched points, but its microblades may, in fact, be parallel-sided flakes. The co-occurrence of crudely flaked notched points with microblades taken from cores using a refined technique seems odd. They occur in thin soils and may represent separate technologies.

Contiguous with Yukon Gwich’in sites are those in the Mackenzie Delta and Anderson Plain. Whirl Lake near Arctic Red River and the Anderson Plain have similar dwellings. The Whirl Lake dwelling lacks timbers and was probably covered with birch-bark and skin, while Anderson Plain pithouses had beams supporting a low turf roof. Both areas have birchbark trays for holding fish, while Whirl Lake shows a varied subsistence of pike, waterfowl, moose, caribou, muskrat, beaver, and dog or wolf. A 10 cm bone snowshoe netting needle decorated with stylized ‘beavers’ represents a rare Dene art object.

East of the Rockies, thrusting lances partially replace the atlatl because they were better tools for killing caribou at close range, as was necessary at water-crossings and corrals. Where rapid-fire hunting was needed on frozen lakes and in open space, the bow and arrow was superior for small subherds, but prior to the bow, the atlatl was used in winter. The change to side-notched arrowheads spread east of the Rockies, down the Peace River to the Northwest Territories to form part of the AD 800-1200 Late Taltheilei phase. Early Taltheilei began 2100 years ago on Great Bear Lake, eventually evolving into the Hare, who used lance and arrowheads until White Contact. Little is known about the Mountain Dene on the Nahanni River, as epidemics and famine reduced them. Up the Liard River as far as Fisherman Lake, Spence River points resembling Prairie Side-Notched arrowheads are interpreted as Slavey Dene.

Northwest Territories-Central Mackenzie District

The Mackenzie District includes the Bathurst caribou range north of Great Slave Lake and east of Great Bear Lake. Its earliest inhabitants were a 6000-3500 year-old Archaic group called Acasta, its side-notched lanceolates being a possible southern modification (Figure 3). A link may exist between its edge-burinated flakes, called Donnelly burins, and multi-gravers and those in Little Arm phase. Other items are large bipointed knives, scrapers, planes, gravers, burins, wedges and a whetstone. Acasta’s 15-25 huge 3-4 m diameter hearths were used in heat-treating quartzite to make it more suitable for flaking. One hearth had charred caribou, bear, beaver, hare, and fish bone. Rare Oxbow, narrow concave-based Duncan and larger convex-based side-notched Pelican Lake points found near Great Slave Lake’s East Arm represent Middle Plains influence.

Dene prehistory is recognized throughout the subarctic by generalized toolkits: bifacial knives, scrapers, wedges, hammerstones, pushplanes, and chithos. Points are the most diagnostic tool for differentiating phases. But most Barrenland surface sites have collections mixed from two or more phases because they are situated at caribou water-crossings used over and over again for millennia. Stratified sites are rare in the Bathurst caribou range, so attempts were made to separate assemblages through estimating the age of raised beach ridges and dating charcoal in isolated hearths. As these were too crude to properly separate the 10 complexes in the 2500-160 year-old Taltheilei Shale tradition, the complexes were assigned to the three well-dated Taltheilei tradition phases in the Beverly caribou range (Table 1). Thus, the Central Mackenzie phases translate as follows: Hennessey is Early Taltheilei; Taltheilei and Windy Point are Middle Taltheilei; and Waldron River, Narrows, Lockhart River, Fairchild Bay, Snare River, and Reliance are Late Taltheilei. Earliest Taltheilei lanceheads are absent in the Bathurst caribou range, casting doubt on Dene movement across the Mackenzie Mountains via the Liard River and strengthening the theory of migrations via the Peace River. Early Taltheilei points are shouldered. Middle Taltheilei lanceheads are stemmed. Late Taltheilei is characterized by notched arrowheads, indicating introduction of the bow and arrow. The last prehistoric phase in the Bathurst caribou range is ancestral Yellowknife, but it would also include Dogrib. In historic times, both Dogrib and Yellowknife built caribou fences on lake ice in March and April, and both hunted migrating Bathurst caribou in the spring. The Bathurst range was taken over by the Dogribs in the mid-nineteenth century after years of friction and two battles with the Yellowknife.

Eastern Mackenzie District (Barrenlands), Northern Saskatchewan, and Manitoba

Hearne was first to record Dene groups following the caribou when he crossed the Barrenlands in 1771. Later ethnographic reports and archaeology confirmed that caribou was the controlling factor in the development of Dene groups on the Barrenlands, in northern Saskatchewan and Manitoba. All Dene groups had to follow the caribou within its wintering area and migration corridor to and from the calving grounds if they were to survive. Alternative food was insufficient to sustain them. Distance between herd ranges and the timing of each respective herd’s migration prevented any one human group from hunting more than one range. Such is the nature of joint culture and herd occupancy that tools and dialects reflect this dependence. Within each caribou range, tools become more homogeneous with time, and differ from those in adjoining ranges because of limited contact between groups. This pattern has been evident since the first peoples entered the Barrenlands. Within the Beverly Range, stratified sites provide a cultural sequence from then until Contact. The association of the Dene tribes with caribou ranges continued into historic times. From northwest to southwest, and with respect to tribal division and range, the Satudene (Hare and Dogrib) occupy the Bluenose caribou range; the Dogrib and Yellowknife occupy the Bathurst range; and the Western and Eastern Chipewyan occupy the Beverly and Kaminuriak ranges (Figure 4).

The earliest people to enter the Barrenland range of the Beverly caribou were Northern Plano who followed the retreating continental ice sheet north. They occupied 34 water-crossings, each having at least one Northern Plano lancehead and dating to 8000-7000 years ago (Figure 3). Northern Plano artifacts are also seen to the south, at Black Lake in northern Saskatchewan. Northern Plano may have merged into Shield Archaic people 6500-3500 years ago, as 121 Beverly sites show no substantial interruption in artifact frequencies, particularly in knives (Figure 5). But their earliest radiocarbon-dated (6120 years ago) small, crude, side-notched point looks nothing like the elegant, long, unnotched Plano points. In time, the Shield Archaic people retreated with incoming very cold climate from the Arctic coast. Hard on their heels were 3500-2700 year-old Arctic-adapted Pre-Dorset people who moved south during this cold period. They left distinctive microblades and cores, burins and spalls, and other refined tools at many Bathurst, Beverly (246 sites), and Kaminuriak caribou range sites (Figure 9). To the southeast, Pre-Dorset artifacts are found at Black

Lake, Saskatchewan, and near Churchill, Manitoba, at the Twin Lakes and Seahorse Gully sites (see Americas, North: Arctic and Circumpolar Regions) (Figure 9).

With climatic warming, Earliest and Early Talthei-lei people moved into the Beverly range via the Peace River (Figure 7), leaving 190 sites in the Beverly range. From 2600 to 1800 years ago, they used long thick lanceheads, then thin shouldered lanceheads. The 1800 to 1300 year-old Middle phase expanded to occupy 355 Beverly sites, reflecting a cultural efflorescence. It also spread east to the Kaminuriak range of Manitoba and southern Nunavut leaving well-made stemmed points as evidence of mass hunting at water-crossings. The 1300 to 200 year-old Late phase people adopted the bow and arrow that is recognized in crude notched arrowheads. These people evolved directly into protohistoric Chipewyan, met by Hearne on the lower Dubawnt River and on the Thelon River’s ‘Arctic Oasis’ at its junction with the Hanbury, where the richest stratified sites occur. The Chipewyan used the bow horizontally, as probably did their Late Taltheilei ancestors. Along the Dubawnt and Thelon rivers, upturned stone slab shooting blinds and stone pile or brush fences used by these bowmen, mark the Beverly caribou migration corridor. The Thelon corridor was especially depended upon, as seen in 16 blinds and 15 fences near water-crossings on the upper Thelon River.

The high quality quartzite, dominant in Taltheilei toolkits, was collected on the tundra and carried hundreds of kilometers south in the fall when the people migrated into the forest. By winter, local stone was under several meters of snow and was of poor quality. Thus, repeated sharpening over the winter of the tools they had carried from the tundra reduced the size of tools in forest sites. Scrapers and knives were serrated and four-sided in the forest zone for easier winter handling and use on frozen hides and meat. Chithos either became more worn because of use on frozen hides or from prolonged winter use before they could be replaced in summer.

World History

World History