At the same time that agricultural societies were expanding into Europe with their rondels, people were also spreading relatively quickly along the Atlantic coast from Portugal to the north of Ireland. This emerging Atlantic Coast culture was different from the already established European tradition in many ways, but most noticeably in its attitude toward death, which was seen dynamically—and dramatically—as a return to the spirit world. This was, of course, nothing new from the perspective of First Society. What was new was the scale of the architectural expression.25 The importance of these structures was not their permanence as such, but that they were part of a process—in which even construction played a part—that defined the interaction zone between the living spirits and the living humans. What prompted these people to first engage in these particular architectural activities is anyone’s guess, but clearly for several thousand years, the activity of finding, moving, leveraging, and ornamenting stones of all sizes was integral to the normal activity of a clan.26

The predominant practice, initially at least, was the collective burial in which remains of numerous individuals were placed together over time in the same tomb.27 Grave goods were usually few. In some tombs there was evidence that the bodies had first been buried or exposed to the elements elsewhere, and it was only the cleaned and disarticulated bones that were placed in the chamber. But this was not always the case: Sometimes bodies were actually buried in the tombs and removed later for secondary burial rituals. At any rate, what is shared is the practice of secondary burial, which is unfamiliar to the modern world, but which was common in this ancient time even in Mesopotamia. At death, the body was buried, but some time later, perhaps a year or so later, the bones were gathered and reburied. It was the second burial that was usually the one associated with rituals. What this did was create a difference between an individual’s death and the role that death played as part of clan cohesion. In that sense, these tombs were not graves in the modern sense, but better thought of as memory devices associated with the telling of stories and legends. They were also ancestor sites, the places where the spirits would return to find their kin, and in reverse a type of portal for the deceased into the realm of the ancestors. It might be useful to think of them as battery-driven magnets, for their job was to attract the good spirits related to ancestors as well as to repel any evil spirits. In this they were not static objects, but continually “active” and indeed, like a battery, in need of being periodically “recharged” through various rituals conducted by clan leaders and their followers.

One could make a comparison with the great mound builders in the Mississippi, which were appearing at about the same time. Both the megalithic structures of the Europeans and the great mounds of the Mississippians were the product of communal activities, both involved ritual activities that had not only to do with ancestry, but also with socializing and trade. The main difference is that whereas the Mississippians are First Society, the builders of the mega-lithic tombs are agro-pastoralists. While the agricultural world did have an important valence in these efforts, the similarities should not be dismissed. If anything, one could argue that the megalithic builders did not so much revolutionize First Society norms as magnify them, not only in the scale of their efforts, but also by integrating them with a culture of animal sacrifices that would have been alien to First Society people.

The rapid spread of this culture along the Mediterranean and Atlantic margins of Europe suggests that maritime contacts between sea-fishing communities played a key part in the genesis and dissemination of ideas. This raises the possibility about beliefs relating to sea and shoreline. Headlands and islands with their dramatic tidal transformations were especially charged with mythological or symbolic associations that may explain the density of these monuments in those places.28 Many of the ritual sites were also probably associated with winter pastures, since they were close to rivers or springs.29

What we have today is only what has survived into the modern era. In Denmark, for example, it is thought that about three thousand megalithic tombs were originally constructed in between 3400 and 3200 bce, but of these only about two thousand remain, which is more than in other places where cities and farming have erased all traces of many of these sites.

What has not survived at all is the living landscape of farmsteads and settlements. People lived in thatch-roofed houses made of basket-like walls reinforced by stakes. Walls were just sturdy enough to support the roof that went low to the ground. Settlements ranged from a single farmstead to small, interconnected hamlets of up to ten or fifteen houses, but larger communities existed only rarely.

The word “megalithic” (meaning “large stone”) used to describe the architecture of this period is no accident, but not all megalithic structures are made from gigantic stones. The various words given to the constructions are cairn, cist, cursus, henge, alignments, menhir, dolmen, cromlech, barrow, portal tomb, and tumulus.

A cairn is a pile of rocks, large or small, that marks a particular spot, sometimes associated with a burial, but not always.

A cist is a small stone-built coffin-like box used to hold the bodies of the dead. It can be uncovered or covered with earth or with even larger constructions. It can be built for both primary and secondary burials.

A cursus (plural: cursi) is an avenue-like construction defined by ditches that crosses the landscape. Some stretched for several kilometers and are mainly found in England.

A henge is an English term to describe a circular arrangement of stones, or timber posts and/or ditches, which can be found singly or in combination.

Alignments are the most mysterious of these constructions. They tend to be in two distinct types, namely large stones with wide spaces and smaller stones more closely spaced. The ones in southwest England will have a special stone at its southern end, often called an altar stone, though its ritualistic purpose is not known. Some alignments form single rows set in the landscape, but in some places they were made as parallel rows.

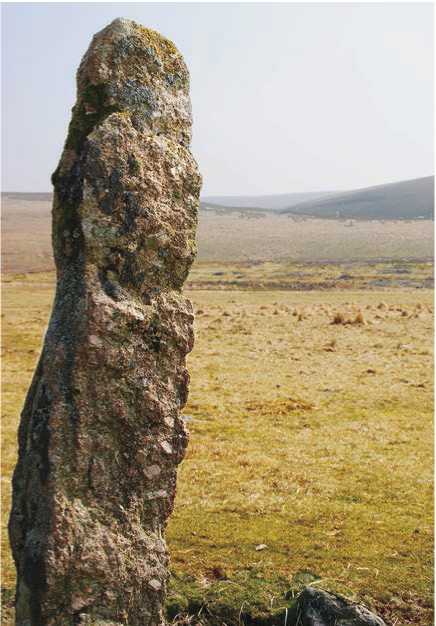

A menhir is a large standing stone that may be found as a single upright monolith, or as part of a group of similar stones (Figure 10.21). Sizes vary considerably, but their shape usually tapers toward the top. Menhirs are most numerous in Ireland, Great Britain, and Brittany, but are also distributed across Europe, Africa, and Asia. The towering 7.6-meter stone called Gollen-stein in Germany dates to around 3000 bce. It was most likely a hero stone, commemorating a great chieftain or warrior. But it could also have served as a territorial marker. The Bible gives us some possible textual clues. “Jacob set up a stone pillar to mark the place where God had spoken to him.

Then he poured wine over it as an ofi'ering to God and anointed the pillar with olive oil (Genesis 35; 14).” The original Hebrew for these stones is tzionim, which strictly speaking means “signs,” but in spoken Hebrew is usually used to denote a stone marking a grave or event.

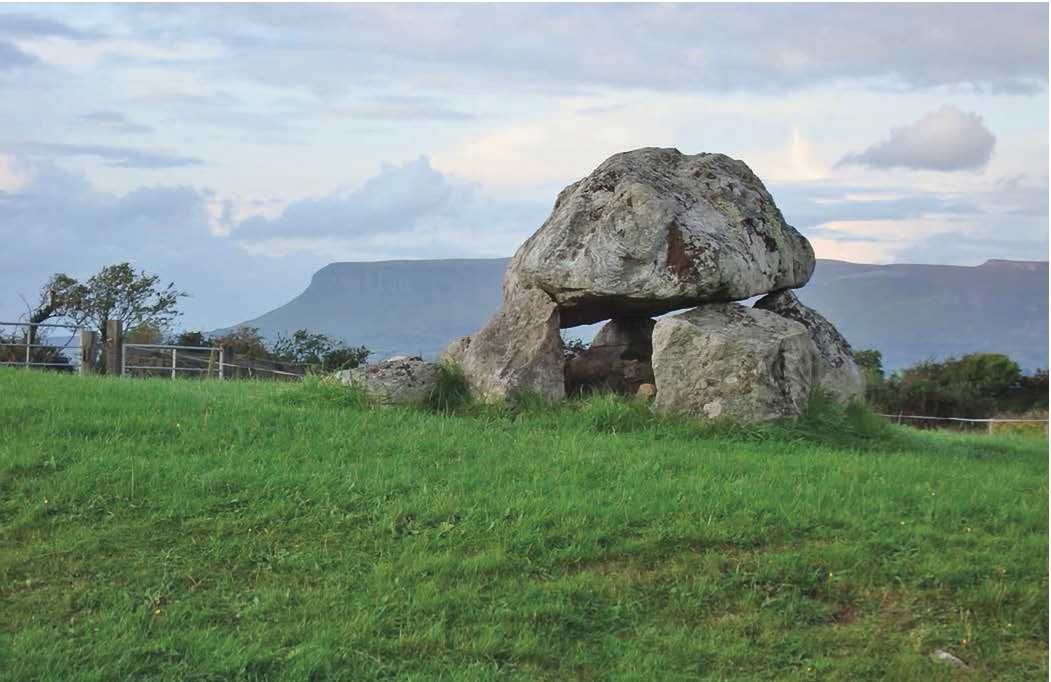

A dolmen (also called a cromlech) is a structure of upright stones supporting a horizontal capstone. It is sometimes called a portal tomb. Each is unique because of the difi'erent size, weight, and texture of the stones that were used, and yet all possess an aesthetic confidence in the “lift” of the stone over the ground. In many places the builders made the stones seem almost weightless.

Designs vary widely from region to region and even in the same locale. Some were made with gigantic boulders, other with small stones. Some are very low to the ground; others stand tall. Some are open and U-shaped. Others, such as examples in Russia, have squarish doors in them. The Damiya-Ala Safat dolmen has two stone rings placed around it. One dolmen in Yemen is square in shape and served three or four tombs and was surrounded by a square enclosure. The dolmen of Crucno in France consists of nine

Figure 10.21: Menhir, Drizzlecombe, South Devon, UK. Source: © Herbythyme (Http://creativecommons. Org/licenses/by-sa/3.0/deed. en)

Massive pillars supporting a capstone weighing over 40 tons. The Bajouliere dolmen, located between the cities of Tours and Nantes in France, is one of the largest in all Europe. The capstone, now broken into pieces, is estimated to have originally weighed in at around 100 tons. It is not a dolmen in the narrow sense of the term, but rather a “portalled chamber” since it has an entrance element and also several internal supporting stones.

If a dolmen is covered with earth or small stones it is called a barrow or, more generically, a tumulus (plural tumuli). However, not all tumuli have a tomb within. And some barrows do not have dolmens inside, but an actual chamber approached through a narrow passageway. For this reason, these tombs are referred to as either “chamber tombs” or “passage graves.” An example of this can be found in the passage grave on Ile Longue, South Brittany, France. At Quanterness in the Orkney Islands of Great Britain, the central chamber is surrounded by six side chambers, all with corbelled roofs. Used for over 500 years, it accumulated the remains of about four hundred people. To make matters even more complicated some of the “passage graves” are not primarily graves, but celestial observatories.

There were two probable ways in which a dolmen or tumulus were built. In one, a rough road of beams was laid in the required direction, and wooden rollers were placed under the stone on this road. Men or oxen then dragged the stone along by means of ropes with other laborers working from behind with levers. The other method was to construct a gentle slope of earth covered with compacted clay that allowed men to move the stone to its final position. The earth would then be removed or used to make the tumulus itself.30 For tombs covered with earth, such as the gigantic Newgrange Mound in Ireland (built around 3200 bce), the builders first secured their base by a ring of large stones, known as kerbstones, that served to hold back the weight of the mound.

In all cases, the selection of the site was important, perhaps near a roadway as a territorial indicator or to be seen from a particular spot in the landscape (Figure 10.22). Many were made to be visible from the valley below, and some were associated with a river. The start of the construction involved certain rituals as indeed did the entire efibrt. At the tomb of Belas Knap in England, when the lintel stone was removed during excavations, archaeologists found the skeletal remains of five children aged between 6 months and 8 years, the skull of a young adult male, bones of a horse and a pig, fragments of pottery, and flint blades that were all part of the construction ritual. 31

Figure 10.22: Megalithic cemetery, Carrowmore, Ireland. Source: © Shira (Http://creativecommons. org/licenses/by-sa/3.0/deed. en)

The orientation of the tombs and almost all of these structures was certainly not random, though the precise reasoning is rarely clear. Most point east, southeast, or south. The clearest examples are the dolmens in Portugal where all 177 known examples fall within the sunrise arc on the eastern horizon. In the chambered mounds, the most beneficial moment seems to have been sunrise at the midwinter solstice, when the sun ended its long autumn waning and was in some sense reborn for the new year. On these days the sun’s rays illuminate the back wall of the chamber. Another special moment was the sunrise at the spring or autumn equinox. Some structures were aligned not to celestial events but to special geographical features. Several are thought to be oriented to the moon. The Damiya-Ala Safat dolmens have an orientation south, which might be because Dumizi was associated with Orion. At any rate, the tombs played the role of both “memory containers” as well as ritual clocks.32

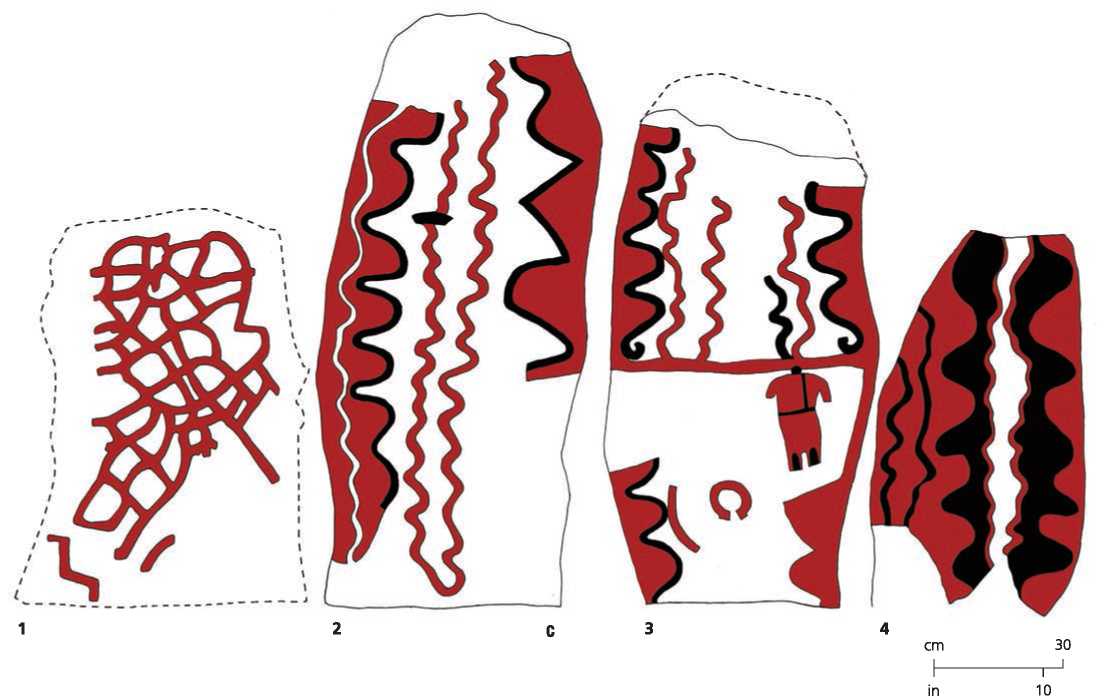

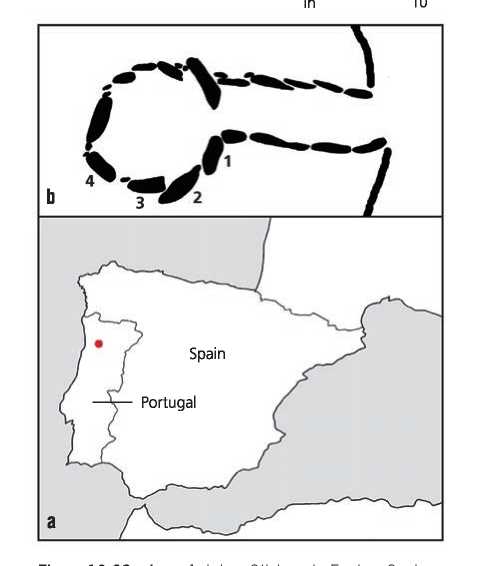

Although many stones seem to have been appreciated for their natural shape, a good number were decorated with spirals, swirls, and zigzags. What is remarkable in this aesthetic is the almost complete absence of identifiable representations of animals and humans. The ancient tradition of Venus figurines is practically nowhere to be found, nor are the animal figurines that litter archaeological sites in Mesopotamia, Egypt, and up into Romania. The realism of cave art disappears and is replaced by a play of circles, zigzags, and lines. It is also more than possible that some parts of the stones were painted. Antelas in Spain has traces of paint on one of the stones that consist of red and black zigzag motifs on a white background (Figure 10.23). If this was not the exception, which it probably was not, we have to imagine something difi'erent from what we experience today, namely surfaces

Figure 10.23a, b, c: Antelas, Oliviere de Fardes, Spain: (a) map and elevation; (b) plan, (c) elevation of stones. Source: Andrew Ferrentinos and Timothy Cooke/Elizabeth Shee Twohig, The Megalithic Art of Western Europe (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1981), 37-38

That were vivid and colorful. This “art” may appear strange and arbitrary to us, but was most certainly not back then. It is likely that it was an extension of First Society body art tradition. It is not just the skin that is activated by patterns and designs, but rocks, which in the process become portals to the world of the spirits. We have to take this into account when we visit these sites. Today we see just the bleached stone, as we would see the Parthenon in Athens. But these stones, like the Parthenon, were probably painted in hues of red, black, and white.

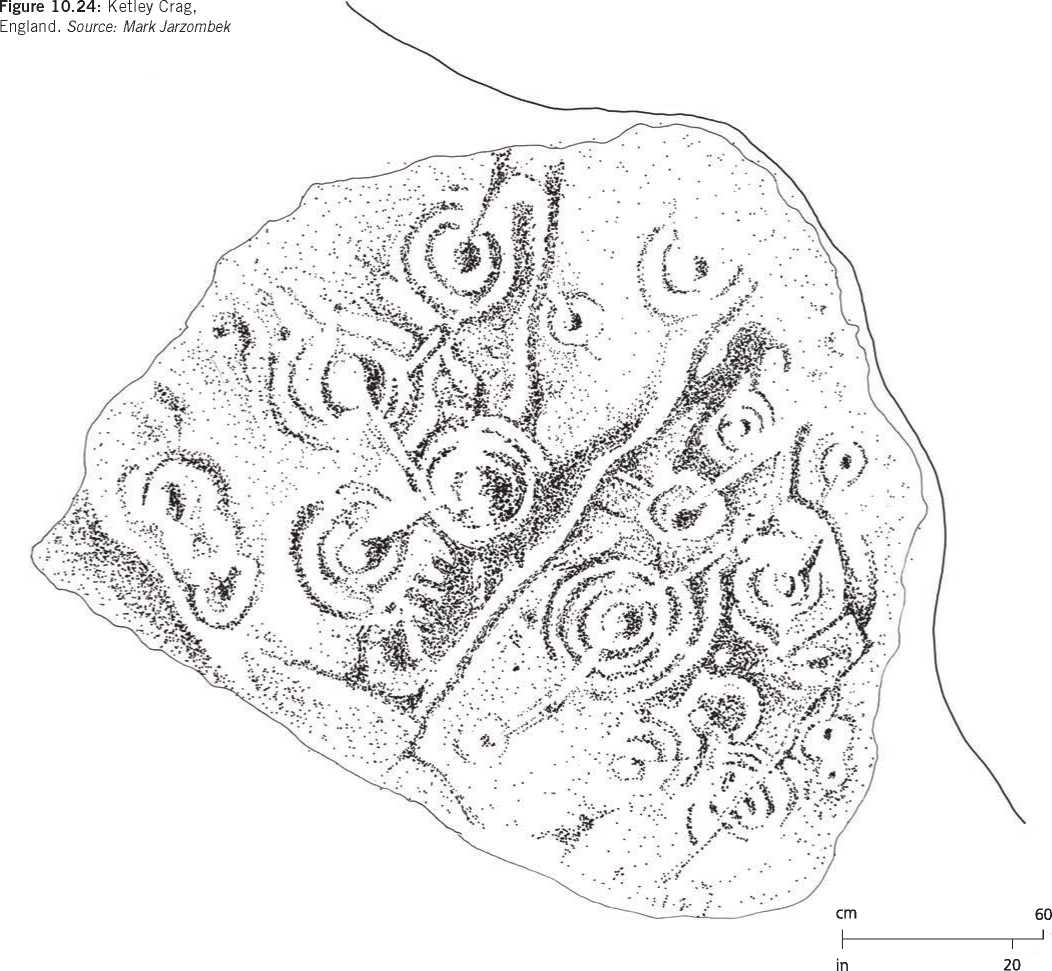

The aesthetic extends not just to stones, but to rock surfaces in the natural landscape. One such place was in Northumberland in northeast England. There, at Ketley Crag, 10 kilometers from the coast, below a settlement at the crest of a hill, the floor of a low and small cave was reworked in an extraordinary way (Figures 10.24 and 10.25). It consists of at least flfl:een “cups” surrounded by rings and connected by grooves, all exploiting the variations in the slope of the rock. Most of the rings seem to have “avenues” connecting to the center of the ring across the ditches. One long groove divides the composition into two parts and runs down the slope of the rock from the rear to the front. Does it represent a type of landscape? Do the rings represent rondels with their causeways? At any rate, its dramatic position in the landscape with

Views across the river Till toward the Cheviot Hills must certainly have played a role. But what? Not too far away are other such rock carvings, such as at Buttony, which consists of two large sets of concentric circles carved on the bedrock of the forest floor with lines radiating from the central cup. The largest in all of England is Roughting Linn, near a small but still beautiful waterfall. More and more of these sites are being found all the time.

World History

World History