The eighth century represents a great rupture of Greek history in the development of the city-state, a rupture that was sometimes called the ‘Greek renaissance’. It is the system created in and for the city-state that characterizes the so-called ‘classical Greece’, a social system that lasted until at least the adventure of Macedonian conquest and the formation of the Hellenistic kingdoms, at the end of fourth century. These four centuries of Greek culture could be better described by means of themes instead of a simple chronological method. We discuss then the major elements of this culture we try to depict: the political sphere (with its civic buildings), the habitat, the economic organization, the religion and Greek main sanctuaries, the funerary customs, and the artistic achievements.

The traditional definition of city, as developed by M. Weber, E. Durkheim, and G. Childe, is: a concentration of population in a particular place, with a specialization of working activities, a public and monumental architecture, a complex social stratification, the use of writing, and the development of internal and external commerce. Most of Greek history and culture were organized in the context of the city-state, that is, independent states composed of an urban center and territory of variable size, which gave the most distinguished elements of what is Greek. The first characteristic that should be clarified is the ‘Greek’ culture: even though we can recognize some elements to be distinguished as ‘Greek’, with the literary evidence to support this statement, a ‘Greek’ culture is an intellectually created affirmation, probably resulting from the wars several allied cities made against the common enemy, Persia. Even the dichotomy between Greek and barbarians only made real sense after those wars, at the beginning of fifth century BCE. Actually, Greece was composed of several independent cities, with different social and political systems of organization, and constantly at war against each other. All these traits continued to be true even after the Median Wars and the Peloponnesian War (opposing Athens to Sparta and their allies); the latter war is the clearest proof of very different organizations of those cities. Nevertheless, before enumerating the different characteristics, one could follow Herodotus’ classical description of what makes Greeks different from the others and similar among themselves: ‘‘the kinship of all Greeks in blood and speech, and the shrines of gods and the sacrifices that we have in common, and the likeness of our way of life’’ (Histories, 8, 144, 2). These are exactly the themes we follow to describe the ‘common Greek’ society.

The Political Sphere

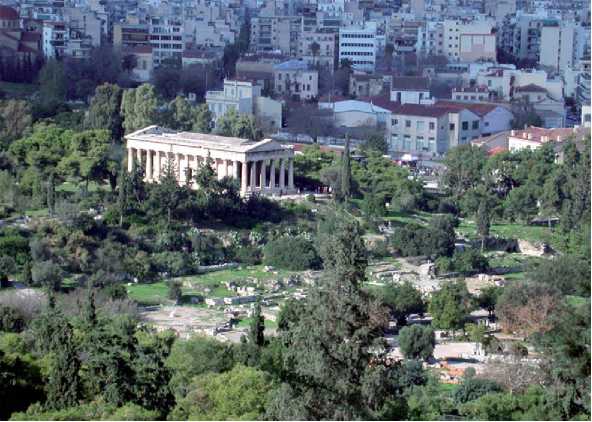

The urban center of a Greek city was composed basically of three parts: the public area of political and economic exchanges, the sacred space, and the residences. The area reserved for the public life was called agora in Greek and it used to house several buildings with specific purposes. One of the best known examples is the agora of Athens (Figure 4), which is also taken as a model by modern archaeologists trying to describe other cities’ monuments. However, recent research has made it clear that Athens is only a well-known example among various possibilities of organizing the public area of a Greek city.

The American School of Classical Studies has excavated the agora of Athens since 1931, after some

Preliminary, nonsystematic excavations. As most of the Greek literature preserved comes from Athens, the work in its agora can benefit from the combination of those two types of data (literary and archaeological); no other city in Greece has as much information and the same quality of data as Athens.

For political purposes, the most important building is the bouleuterion, where the council of the elected representatives would gather to vote the decisions of the city. Several other examples of this civic building can be found in Greece or Asia Minor (Aphrodisias, Assos, Herakleia at Latmos, lasos, Miletos, Nyssa, Priene): they show a variety of size and form but most of those buildings found in mainland Greece are in a bad state of preservation (Argos, Athens, Corinth, Dodona, Megalopolis, and Olympia).

One of the most characteristic buildings of an agora is the portico (stoa in Greek): some agoras seem not to have a bouleuterion, but a portico is present in practically every Greek city. The stoai were places for public gatherings and walking (Figure 5): they offered shelter on rainy or too sunny days; they could also provide shelter for public, religious, commercial, or political activities; they constituted multipurpose buildings. The typical architecture of these buildings is of a long covered space, recognizable mainly by the presence of colonnades, forming a protected place. In the case of Athens, several porticoes were identified, on all four sides of the agora; they are not contemporaneous but they progressively framed the public space. Some of them may also have had some administrative functions, as well as a propitious place to house Solon’s laws (Royal Portico, in the west), where the tribunal could give some of the city’s judgments, such as the famous one against the philosopher Socrates

Figure 4 Athens, agora: the public place (circular tholes in the foreground) and temple of Hephaistos on the left.

Figures Assos, Troad, Turkey, agora: north stoa; on the back wall, we can seethe holes for the wooden beams for an upper story (late Hellenistic age).

In 399 BCE. Public display in the form of inscriptions on steles could also provide information on laws or on next events. When talking about the stoai of Athens, one of the most impressive is the Stoa of Attalos, constructed by Attalos II of Pergamon in the middle of the second century BCE, and rebuilt by the American school to lodge the Museum of the Agora in 1953-56. At the rear of this building, a row of shops links the building with the commercial function of the agora.

Other agorai have been excavated in Greek cities. All of them assume the role of the economic center of the city, with permanent (stoai, shops often with a room for the sales and another room, at the back, for the stock or the workshops) and not permanent structures (such as stalls): on the Competaliast’s agora in Delos, holes in the pavement made of granite plates were brought to light and interpreted as holes for stalls and tents installed on the market day.

Other common types of building present in an agora are the sacred ones (temples or altars), as well as places for social gatherings, such as theaters. In some smaller cities, the same building could perform the functions of theater and bouleuterion, depending on the circumstance. That was not the case in Athens, where one can find, besides the bouleuterion, an odeon (small covered theater) in the middle of the agora, constructed under Roman rule in the first century BCE.

Habitat

Greek habitat may be perceived by various means and should take account of the structural differences between, on the one hand, cities of spontaneous growth, such as Athens and Delos (Figure 6), and planned ones, such as Piraeus, Olynthos, Miletos, or Priene. On the other hand, the habitat comprises either the urban center of a city (called asty in Greek), or residences, farms, and small villages spread in the countryside. Most of our knowledge of Greek habitat comes from the study of urban centers, and good examples are Delos and Olynthos, or the colonial cities in the west (Megara Hyblaea, Selinunte, Poseidonia, Metapontos) and in the east (Chersonesos, Istria, etc.).

Olynthos Olynthos (Chalcidic peninsula) is a famous example of a Greek urban habitat: D. M. Robinson (Johns Hopkins University) excavated it between 1928 and 1939, and J. Vokotoulou is undertaking recent excavations and restorations. The city occupies two flat-topped hills rising to about 30-40 m (the north and south hills) and a section in the plain, east of the hills; founded in the fifth century and unoccupied since its destruction by Philippe II in 348 BCE, Olynthos is of great interest for archaeologists. The ruins preserved the state of the houses where ancient Greeks lived in the fifth and fourth centuries BCE. The main feature of Olynthos is the regular orthogonal plan of the city and the organization of the habitat in blocks: for example, on the north hill, houses were mostly grouped in blocks of ten, comprised of two rows of five houses separated by a narrow alley. Like most Greek houses, they are organized around a central courtyard, often paved, and a portico on one side (generally north). Within this regular plan, however, there is considerable variation, and the uniformity of the house plans is only on the surface. Some houses devote much space to andrones (richly decorated with floor mosaic), kitchens, and other specialized rooms, whereas others have more general-purpose spaces or many shops. The study of the artifacts found in the houses allows working

Figure 6 Delos, theater area: example of spontaneous habitat (Hellenistic and Roman in date).

Hypothesis on the purpose of the rooms and the gender distribution inside the house: this new approach has renewed our knowledge and interpretations of the organization of Greek household.

Other sites inform us on the daily Greek lifestyle: Abdera (Thrace), Kassope (Epirus), and Priene (Asia Minor) are examples of modular Hellenistic houses like the ones in Olynthos. The joint Greek and Swiss excavation of Eretria (Euboia) has revealed oval-shaped houses or houses of apsidal plan, dating to the Geometric Period, as well as houses decorated with mosaic dating to Hellenistic and Roman periods. The mosaic floors also concern the rich Hellenistic houses of Pella (Macedonia), second capital of the Macedonian kingdom, where the archaeologists have discovered a palace. Two other palaces were discovered, completing our knowledge on this kind of residence: the palace of the first capital of the Macedonian kingdom, Vergina-Aigai, dated to the second half of the fourth century BCE, and another in Demetrias-Volos (Thessaly). These impressive (Pella: 60000 m2) but badly preserved sites comprise complexes which surrounded, like the Greek houses, large, open, peristyle and central courtyards. The apartments, the reception rooms, and the functional ones were distributed round these central courtyards.

Territory

One of the major developments of Greek archaeology in the last two decades is the introduction of a different method of research, the survey. This technique consists of the collection of data on the surface and of the identification of constructed structures, covering a large area and broad chronological periods. One of the main intentions of these researches is the identification of settlements spread in the countryside (chora in Greek). The study of the territory of a Greek city is a relatively recent subject for archaeologists and it allows a new approach on ancient Greek lifestyle.

A great part of the society was organized on an agricultural basis, from the calendar (e. g., for festivals and wars) to the economic, political, and social life, since only citizens could own the land and cultivate it. Recent discoveries all over Greece permitted the drawing of a better picture on several aspects, but especially on the organization of the habitat in the form of farms or small villages, as well as new hypothesis of demography estimations, of the economic production of the land, etc. Another evolution is the cooperation of several scientists in the archaeological research: geographers, botanists, zooarchaeologists, among others, are integrated in the archaeological team and search for a broader knowledge of ancient lifestyle.

The first and the best-known example of survey in Greece is the Boiotian Project, started in 1979 and intended to draw a complete picture on this region’s occupation. Since then, several other projects have been proposed almost everywhere in Greece and they have given a much better idea of the ancient rural life. One of the reasons surveys are so wellvalued is that their results are held in the form of quantifiable data, allowing the development of models for the interpretation of the territory’s occupation and the comparison between several regions. Our knowledge of the organization of Greek countryside has improved considerably thanks to this new method; nevertheless, much has been said to reinforce the limits of surveys and the importance of completing them with traditional stratigraphic excavations.

Economic Organization

As in every society, ancient Greece had a specific form of organization of economic life; however, compared with other themes, which are the subject of a clear conceptualization by ancient authors, the economic life was not an aspect of major interest. The word economics {oikonomikos) comes from Greek, but it held a very different sense at that time - it was related to the management of the household {oikos in Greek). The treatises by Xenophon and Aristotle, both named Oikonomikos, were entirely devoted to the administration of the household, in its broad sense, which also included how to deal with the citizen’s family and slaves. Nothing was ever written on how to administer the economy at the city level, or how economic exchanges were organized. Our knowledge has to draw either on the archaeological remains alone or on some short texts {mainly inscriptions) dealing with very specific subjects.

The rarity and the variety of sources {inscriptions, numismatics, and several types of material culture) result in several different interpretations for the economic history of ancient Greece. The reference book by M. I. Finley {The Ancient Economy, 1973) stressed the importance of agriculture as the main source of richness; more recently, the study of some aspects of the long-distance commerce, especially the study of amphorae, has drawn attention to the possibilities of the high economic income merchants could have.

There are basically two issues that favor this reappraisal of the importance of commerce: on the one hand, the developments on the typology of ceramics {whose locality and date of production can be identified much more precisely), and on the other hand, submarine archaeology and the discovery of important shipwrecks with their load {the best-known examples are those of Marseille and Alexandria). These improvements lead to a much broader view of economic exchanges and contribute to their reevaluation. The first and most important conclusion is that, despite some texts {mainly the works of philosophers as Plato’s Laws, The Republic, and Aristotle’s Politics) advocating for an entirely autonomous city as the perfect model, all and every Greek city counted on external commerce.

On the local scale, after a long tradition in Greek archaeology of being interested only in the most impressive monuments {temples, civic buildings, etc.), some aspects of ancient common life have recently attracted attention. In this sense, excavations of workshops and farms as well as surveys made in the countryside contributed to reinforce and improve our knowledge of the economic production.

Religion and Main Sanctuaries

Our knowledge of Greek religious practices has continued to increase since the end of the nineteenth century and the first large excavations conducted by the French School of Archaeology {Delphi, Delos), by the German school {which excavated mainly in Olympia, Samos, and in Turkish sites like Miletos and Didyma), by the Austrian {Ephesos), by the American school {Isthmia, Nemea), and by the Greek Archaeological Service {the Acropolis of Athens, Dodona, Eleu-sis, Epidauros). Those sites are very important for us to approach the Greek way of honoring the gods.

One possible approach to the study of Greek sanctuaries and religion is by the festivals organized in those places. We can start with the Olympic games, as this field shows a recent improvement, due mostly to the Olympic games of Athens in 2004.

Olympia The Germans have excavated the place that gave its name to the Olympic games since the end of the nineteenth century. Whereas a Mycenaean cult center is attested, Olympia {NW Peloponnesus) became important only in the Geometric and Archaic Periods {776 BCE is the date traditionally given for the beginning of the games). The buildings belong to two main categories: worship {temples of Hera, altar and temple of Zeus with the chryselephantine statue - made of gold and ivory - by Phidias), and places linked to the activities of the Olympics {stadium, palaestra, gymnasium, and accommodation). More specific and problematic is the so-called Phidias workshop, a place where the technician certainly sculpted the statue.

Olympic games were organized in four different places, during what is called an olympiad: they started in Olympia, continued in Isthmia and Nemea, then in Delphi, and finished in Isthmia and in Nemea again.

Nemea In Nemea, S. G. Miller {University of Berkeley, California) reconstructed the system of departure of the stadium {in Greek hysplex, which guaranteed a simultaneous start) and allowed a better comprehension of the athletics. The excavations {of the locker room, the passageway to the stadium, the drinking fountains, and the platform for the judges) and the restoration of Nemea, as well as the restoration in Isthmia {University of Chicago), complete our knowledge of the buildings used for Olympic Games.

The following examples complete the panorama of Greek places of worship.

Athens The sanctuary of Athena Polias on the Acropolis of Athens is one of the most famous and well-known religious places of classical antiquity

Figure 7 Athens, Acropolis: the sacred rock from Philopappos Hill.

(Figure 7). Ancient sources are prolific (Pausanias, Plutarch), several researchers studied this place, and a large academic production is available. The excavations were first conducted in the nineteenth century under the authority of the archaeological society (P. Cavvadias) with German contribution (1862-95 mainly); in 1975 began a great campaign of restoration work that is still in progress. The Propylaea, the Parthenon, the Erechtheion, and the temple of Athena Nike are the major buildings of the sacred rock, but our knowledge of this place also concerns the inscriptions (IG I3) and the offerings: statues, specially the archaic maiden of the Perserschutt (the word, owed to German archaeologist W. Dcirpfeld, refers to all the fragments resulted from the Persian vandalization of the Acropolis in 480-479 BCE), bronze statuettes, vases, weapons, little objects.

Eleusis Eleusis, where the Greek Archaeological Society has been working since 1882, is another place of interest in Attica (22 km west of Athens). It was a sanctuary of Demeter, where mysteries were celebrated. Eleusis became a pan-Hellenic sanctuary in the Archaic period under Solon. The main architectural features and the specific archaeological remains of this sanctuary are the sacred well (Kallichoron), the Cave of Pluto, and the Telesterion of Demeter where the secret initiation rites were accomplished. The tel-esterion is a square building with banks of seats on its four sides; here, initiated people watched the mysteries. This kind of building is very specific and belongs to the category of meeting places. Other examples have been excavated: for religious purposes in Samothrace (Sanctuary of the Great Gods), Thebes (Cabirion), and for civic purposes, in several agorai.

Some of the main Greek sanctuaries house oracles: Delphi, Delos, Dodona, Didyma, Epidauros. In Delphi (Phocidia), Apollo spoke to the believer through the Pythia, a priestess; in Delos, in Didyma, and in other places in Asia Minor (i. e., Claros), Apollo also gave oracles. In Dodona (Epirus), it was Zeus’ oracle that spoke by the rustle of the wind in the sacred tree (oak). Asklepios, whose main sanctuary is in Epidauros (but also Kos and Pergamon in Hellenistic and Roman periods), cured the ill, sending them visions. All these practices, documented by ancient texts and archaeological remains, have revealed specific installations, which give us a better idea of the way Greeks consulted the oracles.

Delphi Delphi is a sanctuary of Apollo located in Central Greece, north of the Corinthian Golf, in Phocidia. It was founded probably in the geometric period, c. 800 BCE (but there are some traces of Mycenaean occupation in the surrounding area). The excavations conducted by the French school since the end of the nineteenth century have revealed numerous phases for the altar and temple of Apollo, and several remains of offerings made to the divinity (Figure 8). It is important to notice that, before exploring the sanctuary, the French school and the French government had to move the modern village of Kastro (which developed since the Middle Ages in the location of the ancient ruins). This operation permitted the preservation of one of the most significant religious place of the ancient world. In other places, like Olympia or Delos, which were not occupied since late antiquity, archaeologists did not encounter such problems. Our knowledge of Delphi’s topography owes much to the testimony of the Greek

Figure 8 Delphi, sanctuary of Apollon: theater (classical and Hellenistic periods), Apollo temple (fourth century) under it, and the treasury of the Athenians at the bottom.

Author Pausanias (Description of Greece, Book X) who described the sanctuary in the second century BCE. Historians and archaeologists compared the remains excavated and the text; it results in a possible recreation of the numerous architectural buildings (temples, porticoes, about 30 treasuries) and sculptural offerings along the sacred way (the statue bases are preserved and we can analyze the evolution of the settings of such offerings). The archaeological finds and the ancient sources combined allow us to understand Delphi as a real showcase for the cities which represented at the sanctuary either major events (victories on the barbarians, Persians, or Gauls) or personal acts and commemorations. Delphi was, in the symbolic spirit of Greek mythology, the navel of the world. Neither archaeological nor geophysical studies brought to light explanations about the functioning of the oracle (neither hole in the ground nor divine spirit), famous in antiquity and used by Greeks before every important enterprise (i. e., colonization). Moreover, on the other side of the valley, the sanctuary of Athena Pronaia completes the panorama of this important religious place (temple, treasuries, and a tholos, built in the beginning of the fourth century BCE, the function of which remains hypothetical).

Delos The sanctuary of Apollo in Delos (Cyclades) is one of the main interests of this island deserted at the end of antiquity. The French School of Archaeology started working there in 1873 and the activities (excavations, studies, restorations) still carry on. The oracle of Apollo was the second one after Delphi, and, here again, Delian Festival and games were held every four years.

Didyma The sanctuary of Apollo at Didyma (Asia Minor, 10 km south of the city of Miletos) was a famous cult place with a sacred spring and a grove before the arrival of the Greeks. The Germans all through the twentieth century up to the present have conducted the excavations. Here, the study of the Hellenistic period of the temple gives some information on the oracle: the temple was unroofed; a naiskos in the middle of the court contains the statue of Apollo, whereas an unusual room between the pro-naos and the cella may have served as the Chresmo-grapheion (office of the oracle). A sacred way linked the Didyma sanctuary to the city of Miletos (also excavated by a German team), and much has been learnt on the procession held between these two points from inscriptions and archaeological finds.

Dodona This sanctuary of Epirus (north of central Greece, 20 km south of Ioannina) was famous for the oracle of Zeus, traditionally the earliest oracle in Greece. The earliest archaeological evidence for cult activity dates to the eighth century BCE. Greek excavations (from 1873 up to the present) brought to light the temple of Zeus and a peribolos wall that surrounded the sacred oak (early fourth century), three other temples (Aphrodite, Dione, Themis), and a bou-leuterion. Dodona developed a more monumental character with the rule of King Pyrrhos (297-272 BCE). A theater, a temple of Herakles, stoai, and finally a stadium were added. The theater and the stadium belong to the festival buildings used in Dodona for the Naia Festival (athletic and drama contests) held every four years in honor of Zeus.

Epidauros In Epidauros (on the east coast of the Argolid, Peloponnesus), the sanctuary honored first Apollo (sanctuary of Apollo Maleatas) and then Asklepios, God of Medicine. The excavations began in 1881 (Greek Archaeological Society) and continued in the twentieth century, while the restoration works are still in progress (Committee for the Preservation of the Epidaurus Monuments). In the fourth and third centuries BCE, an ambitious building program resulted in the construction of monumental buildings for the worship (the temple and the altar of Asklepios, the tholos, the abaton, etc.), and later, of convenient buildings (the theater, the hestiatoreion, the baths, the palaestra, gymnasium, stadium, etc.). The theater, the tholos, and the abaton (portico where the sick waited for the god to appear in their sleep) are the most specific buildings of this sanctuary. Porticoes for incubation (abaton) are known in other sanctuaries of Asklepios (Athens, on the south side of the Acropolis, Corinth) or Amphiaraos, hero healer (Oropos, Attica). Like other religious festivals, the Asklepieia (pan-Hellenic athletic and dramatic festival) were held every four years.

Samos, Ephesos Two other sanctuaries give some precious data on the religious practices. The Heraion of Samos (excavated mainly by the Germans between 1910 and 1914, 1925 and 1939, and since 1952) and the Artemision of Ephesos (excavated by the Austrians since 1896) show us examples of an Archaic Ionic temple. In these two places, we can follow the development of the sanctuary from the Geometric Period to Roman time. Ionic order began there, on the west coast of Asia Minor: the archaic temple of Artemis in Ephesos was the largest building in the Archaic Greek world and the first large structure to be built entirely in marble. The temple, reconstructed after a fire in 356 BCE, was considered as one of the Seven Wonders of the World. The special features of the soil in the Heraion of Samos ensured the preservation of ivory and wood artifacts, which is very rare; in the Ephesos’ so-called Artemision, many little offerings were discovered and inform us on the cults celebrated there in the Geometric Period, before the construction of the archaic temple (so-called Cresus’ temple).

Necropolis - Mausoleum: Funerary Customs

The archaeology of death is one of the most productive fields of our discipline. The funerary custom is an important element in the definition of a society: its regularity and diffusion in space may shed light on the extent of a given community. The type of tombs (sarcophagus, funeral urn, tumulus, for an individual or for a family, etc.), the funerary ritual, the treatment of the corpse (incineration or inhumation), and the artifacts buried together with the deceased inform us of the physical characteristics and the social status of the deceased, as well as the religious beliefs of the community.

We choose to comment on four sites, ranging from the Proto-Geometric to the fourth century BCE, that illustrate archaeological concerns of the twentieth and twenty-first centuries: the heroon of Lefkandi (Euboia), the cemetery of the Kerameikos in Athens, the mausoleum of Halikarnassos (Asia Minor), and the royal necropolis of Vergina (Macedonia).

The British School of Archaeology in Athens excavated the heroon of Lefkandi during the 1980s. The excavation of the Toumba cemetery has brought to light a long and narrow, apsidal building dated to the first half of the tenth century BCE. It measures c. 50 x 13.5 m2, and a row of holes for wooden posts surrounds the building. Other holes, in the center of the building, are the remains of the inner colonnade: the heroon, like the first Archaic temple in stone, had an axial colonnade. Two burial shafts were uncovered inside, one containing the skeletons of four horses, the other both the inhumation of a woman and the cremation of a warrior. They were rich in offerings, some of which were imported, and show the exchanges between Greece and Near East at that time. The structure has been interpreted as a local ruler’s house, which, after his death, was covered with a mound and converted to a heroon.

The cemetery of the Kerameikos in Athens was explored first by the Greek Archaeological Society (1863-1913) and since 1913 by the German Archaeological Institute. These excavations allow us to understand on a wide scale the funerary practices of the rich Athenians from the sub-Mycenaean and ProtoGeometric periods to the late imperial Roman time. This cemetery includes private graves, tumuli with several burials, public burial monument (the demo-sion sema), and peribolos tomb. All these funerary structures have revealed rich material that gives an idea of the citizens buried there. The monuments discovered over the tomb, statues (kouroi and korai), steles, or naiskoi, give several examples for the history of art of both Archaic and classical times (Figure 9).

Among the important discoveries of the nineteenth century, we have to consider the mausoleum of Hali-karnassos. This is an eponymous monument: we name this kind of funerary structure after the Mausolos

Figure 9 Athens, Kerameikos cemetery: the Street of the Tombs, with classical funerary monuments (mostly fourth century BCE).

Dynasty of Karia who died in 353-352 BCE. Charles Newton, who removed many of the sculptures to the British Museum, excavated the site in 1857. Excavations resumed under Danish direction in 1966. It is a huge construction (total height of monument c. 57.6 m) made up of a tall podium (with two or three steps), a cella surrounded by a peristyle, and a pyramidal roof crowned by a sculpture. The mausoleum associates Greek features and local, indigenous ones. Greek sculptors came to Halikarnassos (following ancient authors Pliny and Vitruvius) - we can see it in the relief friezes which decorate the monument - but the entire structure owes much to local traditions, for example, the Lycian pillar tombs and the Nereid Monument of Xanthos. Nowadays, researchers place emphasis on all these influences and on the relations between the funerary structures of Greek cemeteries (like the Kerameikos) and those ones.

In 1977, Greek archaeologist Manolis Andronikos discovered the royal necropolis of Vergina (Macedonia). Vergina-Aigai was the first capital of Macedonia: archaeologists brought to light the palace and a large number of tombs (from the tenth to the second century BCE). A huge tumulus, 110 m in diameter containing three vaulted tomb chambers and one cist grave, lies on the western edge of the necropolis. These royal burials of the last third of the fourth century, with their well-preserved painted decoration and rich contents (gold and ivory artifacts, weapons, crimson-purple fabrics, ruins of funerary furniture) are among the most spectacular recent discoveries of Greek archaeology. Tomb II, with a royal hunt painting on the front, has been identified as the tomb of Philip II, father of Alexander the Great. Vergina and other Macedonian tombs (Lefkadia, Aghios

Athanasios) are now being published by their Greek finders or curators.

Artistic Achievements

Ancient painting When we talk about ancient painting, we have only a few works of art to look at: Minoan and Mycenaean wall paintings are often fragmentary; almost nothing is preserved from the Classical period. The Greek author Pausanias gives some rich descriptions of mural paintings in Delphi’s Cnidian Lesche (by Polygnotos), of the panels in the Stoa Poikile (painted stoa) of the Athenian agora (by famous Athenian artists), or in the left room of the Acropolis Propylaea, but nothing has survived. The only possible example of a classical Greek painting is to be found in the colonial context of the Tomb of the Diver in Paestum (Figure 10). The tomb formed by four slabs and one lid, all of them painted, was dated to 480 BCE. The very characteristic of painting the inside of a tomb and certain aspects of the iconography put some doubts on the identification of the tomb as Greek. On the other hand, the tomb belongs to a Greek city, and the style of the paintings is comparable to the contemporaneous Greek ceramics. For the Archaic and classical periods, in terms of Greek painting, the black or red painted vases (produced in Greece mainly between c. seventh and third century BCE) remain the most reliable source.

However, recent archaeological discoveries in the north of Greece (Macedonia; see also the discussion on cemeteries) invite us to a new approach to the ancient authors whose writings on painting and color have been feeding the collective imagination of artists, philosophers and historians since the

Figure 10 Paestum National Museum, south Italy: Tomb of the Diver, detail of the lid with the diving scene (c. 480 BCE).

Renaissance. Recent books bring a new way of looking at the links between Roman and Greek paintings: the first are sometimes inspired by the second, when they are not copies of Greek famous creations, as the Roman author Pliny the Elder, for example, reported (Natural History, XXXV). Archaeometry and new techniques of photographic analysis (infrared, ultraviolet, etc.) complete iconographic and stylistic studies: analyses and characterization of the pigments and the painting techniques used on Macedonian, Thracian, or Alexandrian monumental tombs, on the Hellenistic paintings collection of Louvre Museum in Paris, on the funerary stele of Demetrias-Volos, revealed the characteristics of this kind of painting (monumental and funerary) and allow some more precise considerations.

On the other hand, the discipline has seen a renewal of the studies on the Roman wall painting (like for the Greeks’, Roman portable panels disappeared) of the Pompeii, Herculaneum (Campania), or Farnesina (Rome) villae. Current research starts from the four styles defined by A. Mau in 1899 (Style I, incrustations simulating marble of various colors and types on painted plaster; Style II, architectonic or architectural, artists imitated architectural forms by pictorial means; Style III, ornamental, under Augustus’ reign; Style IV, heterogeneous) to define and specify features that depend on the geographical, historical, political, sociological, and of course architectural contexts.

Our knowledge of ancient painting has recently improved not only with these late classical and Hellenistic discoveries, but also with the renewal of the study on protohistoric painting.

Cycladic wall paintings were brought to light in the south Aegean islands of Santorini (frescoes of the ancient habitations in Akrotiri-Thera, excavated by

S. Marinatos, then by Ch. Doumas (Archaeological Society at Athens, since 1967), Melos (Phylakopi), and Keos (Ayia Irini, University of Cincinnati since 1960); Minoan paintings were discovered in Crete (palace of Knossos, Ayia Triada, villae of Amnisos and Tylissos in the surroundings). All the figurative paintings are neopalatial in date (1700-1450 BCE). The frescoes of Akrotiri-Thera are now exhibited in the Museum of Prehistoric Thera and in the National Museum in Athens, while restoration works are now being conducted on the site. The frescoes of Knossos, discovered by Sir Arthur Evans, are exhibited in the Herakleion Archaeological Museum; copies are on display for tourist purposes on the site.

The Minoan frescoes have different sizes: some of them covered the wall in its whole height (e. g., the ‘saffron gatherer’), others were under life size (taur-eador fresco) or miniature (in this case, the paintings emphasized architectural parts like the doors or windows). Distinction can also be made between the subjects: among the frescoes with human and animal representations, we find bull-leaping and bull-catching compositions, boxing and wrestling scenes, processional scenes; there are also formal patterns or heraldic animals on a large scale (frieze of ‘figure-of-eight shields’ or ‘griffins flanking throne’) and, finally, decorated floors (the dolphin fresco, restored by Evans like a mural, probably collapsed from the second story).

Mycenaean paintings were discovered in the palaces of Mycenae (H. Schliemann, Greek and English excavators), Tiryns (H. Schliemann and W. Dcirpfeld), and Pylos (palace of Nestor, paintings first published by M. Lang, 1969), and also in Orchomenos and Thebes; some of the Knossos murals are Mycenaean because they were painted when the Mycenaeans came to Crete c. 1450 BCE.

Mycenae and Tiryns are well known by archaeologists and historians. In Pylos, where the frescoes that stood on the walls at the time of their destruction have survived in great number, the present purpose is to restore the paintings trying to reconstruct the decorative program from the huge quantities of fragments. The Pylos Regional Archaeological Project (“multi-disciplinary, diachronic archaeological expedition formally organized in 1990 to investigate the history of prehistoric and historic settlement and land use in western Messenia in Greece, in an area centered on the Bronze Age administrative center known as the Palace of Nestor,’’ University of Cincinnati and other contributions) is one of the programs which illustrates the association of researchers in order to improve our knowledge on a place or an area. In this context, chemists, physicists, archaeologists, and art historians work together and produce new results that give another idea of the ancient artifacts, way of life, etc. Ancient recreations of the Mycenaeans paintings of Pylos have been checked, completed, or changed, while new ones have been suggested; some fragments have revealed clearly traces of painting or patterns.

Sculpture In this article, we cannot take into consideration all the recent discoveries and improvements in the study of ancient pieces of art. We can only mention the direction taken by art historians who are dealing with Greek sculpture. Marble originals, rare bronze originals (often discovered under the sea), or Romans copies of both continue to impress visitors of antique museums. The reception, the visual perception, and the setting of the statues are nowadays subjects of study, as well as the use of color or gilding on marble sculpture. It is neither the career of one sculptor, nor the stylistic or iconographic studies, which mainly interests the art historians and archaeologists of the twenty-first century: they want to understand Greek sculpture from the quarrying of the block in the quarry to the workshop of the sculptor, and from there to the place of exhibition (Figure 11).

Ceramics The same shift of interest has also happened in the study of Greek ceramics. In the beginning, archaeologists cared only for the beautiful pieces of art of painted vases; more recently, scholars are more preoccupied in defining typologies and in making them more accurate. In a broader sense, the modern approach aims at constituting precise corpora either of forms with accurate dating or in a reappraisal of those painted vases, trying to show evolutions of style and of subjects represented. The study of everyday vases, and particularly amphorae, permitted assessment of some aspects of the organization of ancient daily life. Analyzing the paintings, researchers are trying to account for the messages those images could convey, contributing thus to a better comprehension of the values of those societies and their symbolic meanings.

A new approach that sees material culture as an indication of the people’s identities (mainly grouped under the term ethnicity) is perceptible in the study of Greek ceramics, either in the constitution of typologies or in the analysis of representations and symbolic meanings of images.

Recent improvements in Greek archaeology are now allowing the reduction of the differences of approach between a more traditional one, based essentially on classics, and a more conceptual one, influenced by an anthropological method developed initially for prehistoric archaeology. Those two approaches have much to gain from each other and Greek archaeology is the perfect field for that encounter, as it is a privileged area, containing extensive

Figure 11 Samos, Greece: the cast of the sculptural group offered by Geneleos (beginning of the sixth century) is set up on the site, while the original pieces are in Samos and Berlin museums.

Written documents as well as very broad material culture that can touch all aspects of past life, from poor people’s daily life to high-level artistic and economic achievements of the elite.

See also: Asia, West: Roman Eastern Colonies; Ceramics and Pottery; Civilization and Urbanism, Riseof; Classical Archaeology; Ethnicity; Europe, South: Greek Colonies; Rome; Historical Archaeology: Methods; Landscape Archaeology; Ritual, Religion, and Ideology.

World History

World History