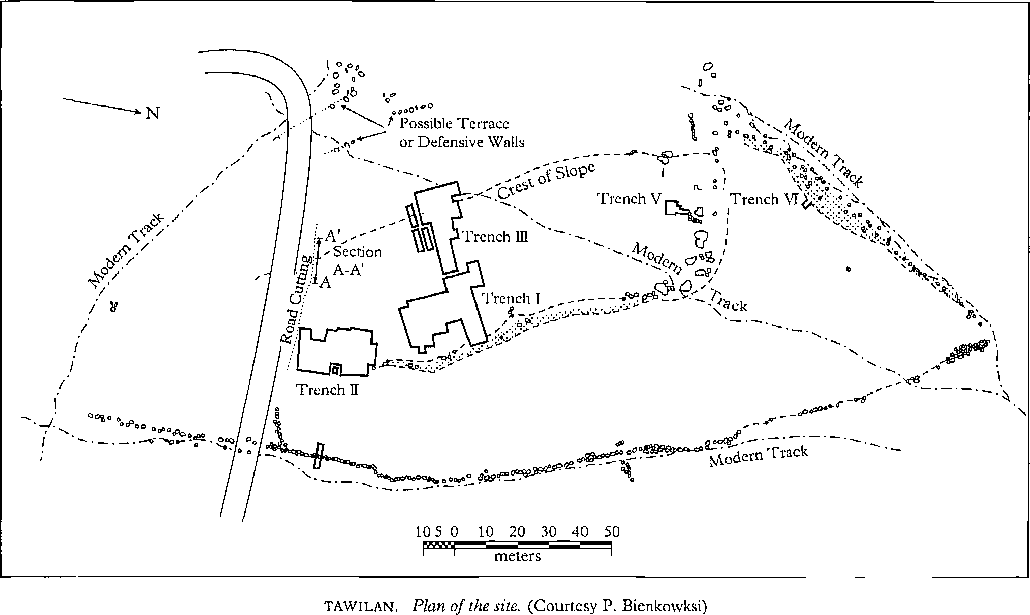

The nortlTwest and on the soutlt. Bennett excavated three main areas (I-III), and three small test trenches (IV-VI). Her excavations failed to validate Glueck’s identifications: they instead revealed an unfortified, essentially agricultural Edomite town, whose occupation can be divided into eight stages. The first five, based on their pottery, date to Iron II, probably the seventh-sixth centuries bce.

In the first settlement stage Bennett discovered a series of pits dug into the natural clay that were unrelated to surfaces or strucmres. In tlie second stage foundation walls had been built on a stone and clay fill used to level tlie ground. All three areas consisted of rectangular buildings with dry-stone walls that had been built on a nortlieast-soutliwest axis. Areas II and III revealed well-built structures with solid walls, stone paving, and pillars. In the third stage walls were added between the pillars in areas II and III. Major architectural additions followed, including steps to higher ground in the area III buildings. In area II were remains of a building of inferior construction whose plan could not be determined. In the fifth stage, all tliree main areas were destroyed, some by fire, followed by a limited occupation by squatters in area

III. The other areas were destroyed and abandoned. In tlie sixth stage (c. first or second century ce), area II became a cemetery and areas I and III were abandoned. In the seventh stage (Mamlulc period) a rough wall to mark a field boundary or a terrace wall was constructed in area II. In the final stage of occupation at the site (Mamluk period or later), a square structure (one of Glueck’s towers) was built in area II.

Material Culture. In her 1982 season, in fill deposits in area II, Bennett recovered the first cuneiform tablet ever found in Jordan, a legal document from Harran in Syria. In the tablet testimony is given regarding the sale of two rams. The name and patronymic of the man responsible for tlie testimony are Edomite—they are compounded with the name of the Edomite god Qos. The tablet has been dated to the accession year of one of the Achaenienid kings named Darius: Darius I (521 bce), Darius II (423 bce), or Darius III (33s bce), although certain attribution is impossible for an isolated text.

In 1982 Bennett also recovered the first large hoard of gold jewelry in Jordan, eighteen gold rings and earrings (along with 334 carnelian beads). The pieces were discovered inside a badly encrusted bronze bowl attached to a thick coarse-ware sherd. The bowl had been set into tlie sterile clay close to a burial pit, but it was not possible to prove conclusively any association between the hoard and the burial. It was originally suggested tliat tlie jewelry was of various dates between the ninth and fifth centuries bce. However, more recent study indicates all tiie jewelry dates to tlie ninth-eighth centuries bce.

Dating tlie occupation at Tawilan and at all Edomite sites is problematic and subject to revision by future discoveries. [See Umm el-Biyara.] The Iron II pottery, presently dated to the seventli-sixth centuries bce, may be earlier. The cuneiform tablet from Tawilan, tliough not from an occupation level, nevertheless indicates some activity tliere during the Persian period. Future excavation may prove that occupation continued through the Persian period.

[5ee also Edom; and the biographies of Bennett and Glueck.]

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Bennett, Crystal-M, “Excavations at Tawilan in Southern Jordan, Levant i6 (1984): 1-23. Basic preliminary excavation report; should be read in conjunction with Bienkowski’s reappraisals (below).

Bienkowski, Piotr. “The Chronology of Tawilan and the ‘Dark Age’ of Edom.” Aram 2.1-2 (1990): 35-44. Assesses the archaeological evidence for continuity of occupation beyond Iron II at Tawilan. Bienkowski, Piotr. “Umm cl-Biyara, Tawilan, and Buseirah in Retrospect.” l?vant 22 (1990): 91-109. Reevaluates the excavations and suggests refinements to the excavator’s phasing and dates (see pp. 95-101).

Piotr Bienkowski

TAYA, TELL, site located in nortliern Iraq (36°! i' N, 42°43' E). The modern Arabic name. Tell (Tall) Tayah, applies properly only to the central mound of the site but has been extended to cover the entire ancient settlement. The name has no meaning to local Arabs; it may be connected with the Tai ttibe. The spelling Tall Teir used by Seton Lloyd (1938, p. 137) is a mistake. Local Turkoman describe Taya as an encampment of Timur Lang, to whom they ascribe a natural formation resembling a hollow road tlirough nearby foothills. Taya probably had four ancient names. About 2500-2000 BC it developed into a substantial town witli most likely a Hurrian population and tlien declined and was abandoned. About 1900-1800 it was reoccupied and became a large village likely to have been called Samiatum or ZamiaUim, an apt name to describe the extensive ruin it then was, because the word means wall foundations in Akkadian. The name is attested in contemporary administrative records found at tlte regional center of Qatara (Dailey, Walker, and Hawkins 1976, p. 178) and is the only toponym on an official document found at Taya (J. N. Postgate, in Reade, 1973, p. I74ff.). About 850-600 Taya was a small castie, and there was a village on the site about ad 1000-1250; its names in these periods are unknown.

Taya lies on the lower southwestern slope of a range of limestone hills, outliers of the Zagros Mountains, overlooking the Sinjar-Tell ‘Afar plain. It is one of a complex of four major sites, among many smaller ones, in the plain’s northeastern corner. This area is bordered by hills to the nordi and northeast with passes tlirough them, by tlie smaller Mu-hallabiya complex of sites to the southeast, by steppe country with fewer sites to the south, and by the extensive Sinjar complex of sites to tlie west. Taya itself was the most important regional center in the mid - to late tliird millennium.

Equivalent centers at other dates being Karatepe/Tell el-Jol 6 km (3.7 mi.) to the west (Hassuna through Ninevite 5, Hellenistic), Tell er-Rimah 12 km (7.4 mi.) to tlie south-southwest (Old Babylonian Qatara; Neo-Assyrian Za-mahu), and modern Tell ‘Afar 4 km to tlie northwest (Umayyad Qal‘ali Merwan, ‘Abbasid, Ottoman). [5ee Hassuna; Rimah, Tell er-.]

Various calculations suggest that these centers with dependent villages could have held populations in the range of fifteen tliousand to twenty-five thousand persons, supported by at least 300 sq km (115 sq. mi.) of agricultural land, extensive grazing land in the hills and steppe, and small irrigated gardens. Annual rainfall in this area is usually over 20 cm (50.8 in.), suitable for dry farming of cereals; the soil is good, and die flora and fauna were originally much richer than they are today. Food remains from third-millennium levels at Taya Q. G. Waines, in Reade, 1973, pp. 185-187) include carbonized seeds of barley (Itm-deum mdgare), wheat (tnticum aestivum), some emmer wheat (triticum dicoccum) possibly as a weed, varieties of pea, lentil, grape, a cucurbital species, and apparently olive stones, although it has since been suggested that tire last may be animal droppings. Animal bones (S. Bokonyi, in Reade, 1973, pp. 184-185) mainly derive from sheep or goat, pig, and gazelle, also from onager and cattle or aurochs. It is an open question whether gazelle were domesticated. Fallow deer, wild pig, and badger are also attested, and incised drawings on third-millennium pottery show fish, large birds (ostrich or bustard?) and large ruminants.

The site spreads across some 155 ha (383 acres), of land, on eitlier side of Wadi Taya, a seasonal stream feeding Wadi ‘Abdan and Wadi Thartlrar, and today has access to perennial waterholes and bitter water. Modern cultivation encroaches from the southwest. An all-weather track along the foothills traverses the site from northwest to southeast, as one did in the tliird millennium, and there are possible traces of an ancient direct track northeast over the hills toward Abu Maria (ancient Apku) and the Tigris Valley. About i km (.6 mi.) downstream of the central mound of Taya is the prehistoric site of Tepe Mahmud Agha, whose inhabitants presumably utilized the same resources as those of Taya did subsequently.

Taya was first recorded by Lloyd (1938, p. 137), among possibly Islamic sites, and described as “probably Roman.” This dating, sensible at the time, was probably based on the abundance of visible stone wall-footings and on numerous large incised third-millennium sherds then regarded as Par-tho-Sasanian, a mistake that has probably resulted in many false datings of nortliern Iraqi sites. Taya was identified as mainly tliird-millennium by J. E. Reade on a visit in 1964, and excavated under his direction in tliree seasons, 1967,

World History

World History