In spite of a vast body of literature on the Megalithic material culture, hitherto no comprehensive effort had been made to collate the data against an ecologic and systemic framework. The priorities and perspectives of the earlier researchers different as they were, devoted much of their efforts to the reconstruction of culture histories. The complex questions related to the Megalithic modes of production, relations of production, aspects of social differentiation, and societal organization remained largely unfocused.

However, the recent quantitative evaluation of the material data of the Megalithic period, as also its collation against an ecologic and systemic framework, has indicated that a combination of specialized strategies, that is, agriculture and cattle pastoral-ism, was adopted at the societal scale of production. The Megalithic sites located in the physiographic zones of Wardha-Penganga plain, Wainganga basin, Middle Krishna valley, Rayalaseema plateau, Andhra Ghats south, Dharwad plateau, Bangalore region, Mysore region, South Malnad, Mettur-Vellore region, Coimbatore uplands, the Palar-Ponnaiyar basin, the Vaigai-Tambraparani basin, and South Malabar unambiguously indicate these subsistence strategies. It is important to note here that a majority of their settlement sites are located either on the banks of major rivers or on their major tributaries and most of the burial sites are situated within a distance of 10-20 km from the major water resources. The following facts may also be suggestive of this substistence strategy: (1) the maximum concentration of their sites in river valleys and basins and preference shown toward occupying black soil, and red sandy-loamy soil zones; (2) the distributional pattern of these sites in rainfall zones where the average annual precipitation ranges from 600 to 1500 mm; as also (3) the occurrence of maximum number of their sites mainly in tropical dry deciduous, tropical thorn, and tropical moist deciduous forest zones avoiding as they did other dense forest zones.

Figure 7 Urn burial with cairn packing and boulder circle. Madavilagam (Chengalpattu district, Tamilnadu, India). Courtesy: Archaeological Survey of India.

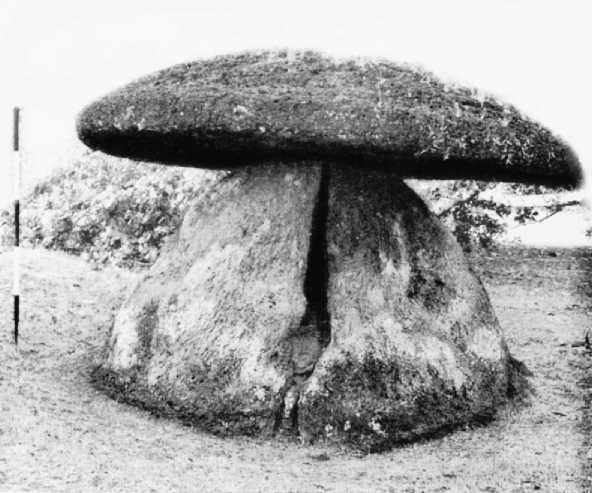

Figure 8 Urn burial capped by a slab and covered by a Topi-kal (hat stone). Cheramanangad (Thrissur district, Kerala, India). Courtesy: Archaeological Survey of India.

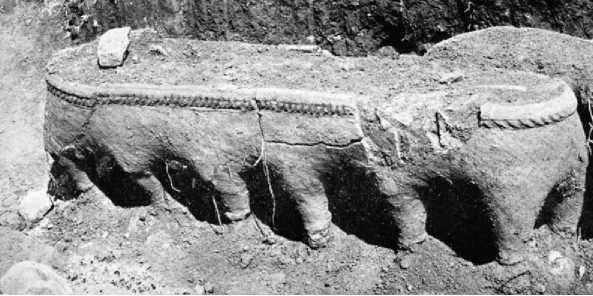

Figure 9 Legged sarcophagus burial with cairn packing. Pallavaram (Chengalpattu district, Tamilnadu, India). Courtesy: Archaeological Survey of India.

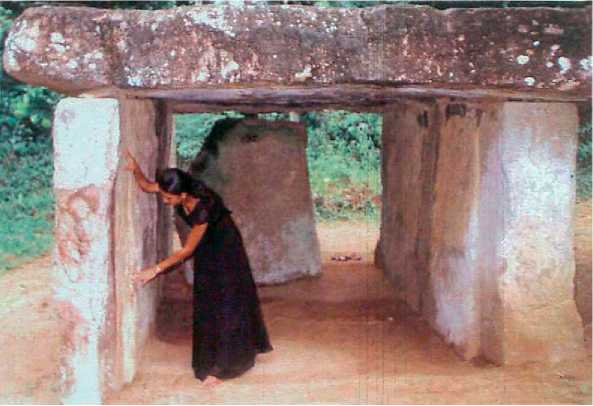

Figure 10 Dolmen (Chamber open on one side). Padavigampala (Kegalle district, Sri Lanka). Courtesy: Deccan College Postgraduate and Research Institute.

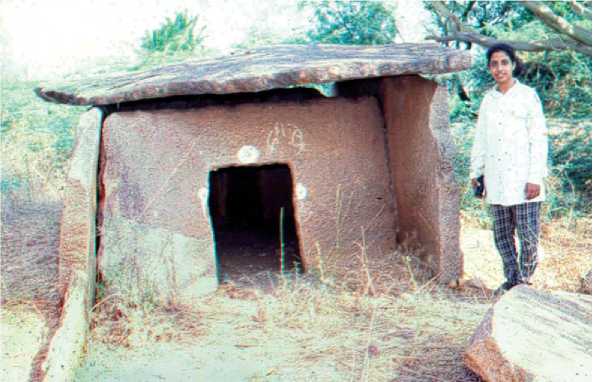

Rajanakoluru (Gulbarga district, Karnataka, India). Courtesy: Deccan College

Figure 11 Portholed dolmen (A closed chamber). Postgraduate and Research Institute.

However, the predominance of pastoral traditions which is seen in the present distribution of Kuruvas (who are mainly sheep/goat pastoralists), and Gollas (who are mainly cattle pastoralists but also keep small number of sheep/goats) in southwestern Andhra Pradesh, northwestern Karnataka, and northwestern Andhra Pradesh comprising Telangana, Rayalaseema peneplain, Andhra Ghats south, and North Maidan regions may indicate greater inclination toward pastoral subsistence strategy. This may be due to ecological stresses and greater economic advantages provided by this subsistence strategy. Although there is a very strong evidence of cattle pastoralism in these regions, currently archaeological evidence lacks concerning sheep/goat pastoralism. This lacuna seems to be mainly due to the lack of efforts for finding out evidence. However, this can be taken as a working hypothesis and future investigations must seek them. Nonetheless, these aforementioned divergent economic patterns, which seem to have then prevailed, as is the case even now, were not isolated but had a symbiotic relationship with each other.

Their subsistence base was a specialized agropastoral economy dominated by cereal, millet, and pulse production: there seem minor variations in the agroeconomy of the area. There is evidence for the occurrence of wheat, rice, barley, kodo millet, and pulse crops in Vidarbha (Wardha-Penganga plain, Wainganga basin); barley, rice, kodo millet, and pulses in the Middle Krishna valley and Andhra

Ghats south area; and, the remaining parts of South India have mostly produced the evidence of rice, ragi, kodo millet, and pulses. The cattle (including buffalo) predominates over other domesticated species and

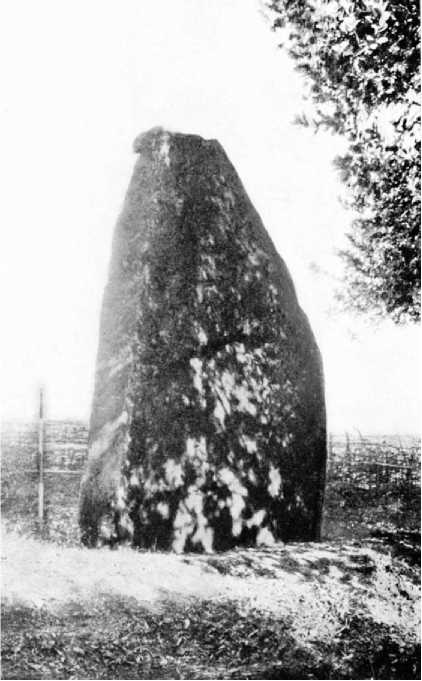

Figure 12 Menhir (A monolithic slab). Anapara (Thrissur district, Kerala, India). Courtesy: Archaeological Survey of India.

Invariably, in all these sites it accounts for more than 60% of the total faunal assemblage; whereas sheep/goat accounts for only 10-15% and was next only to cattle in importance. This suggests that first the earlier Neolithic tradition of cattle keeping was continued and second it clearly brings home that cattle pastoralism and not sheep/goat pastoralism formed a major preoccupation of the Megalithic society. Thus, irrespective of the variations in agriculture, cattle herding seems to have formed a major preoccupation of the Megalithic society in all these areas.

There is enough evidence that many of the known 400 settlement sites of this period testify that industrial activities such as smithery, carpentry, bead making, and pottery manufacturing were carried out, displaying as they do a highly developed tradition in these crafts. The items of exchange seem to have consisted mainly of iron tools and weapons, copper and gold ornaments, semiprecious beads, and pottery. Although it is not possible at this juncture to give a clearer picture of exchange network of various items in this area, the following areas seem to be major zones of industrial activities.

Kumaun area for iron working; Wainganga basin (or Nagpur plain) and Wardha-Penganga plain for iron, copper, silver, and semiprecious bead working; Telangana peneplain, Rayalaseema peneplain, Gulbarga plain, Bijapur region, Dharwad plateau, and Raichur plain for iron, copper, and gold working; Bangalore region, Mettur-Vellore region, and Coimbatore uplands for iron, gold, and semiprecious bead working.

The location of several large Megalithic sites on the known early historical trade routes leaves a strong

Figure 13 Avenue: Vibhutihalli (Gulbarga district, Karnataka, India). Courtesy: Archaeological Survey of India.

Possibility of these acting as places/centers for exchange. Although the gravity of exchange mechanism and patterns of consumption still need to be understood, the hierarchical nature of sites and occurence of nonlocal prestige goods such as gold, marine shell, lapis lazuli in Megalithic burials leave little doubt about the inter-regional circulation of these goods. Besides indicating long-distance trade, it also shows growing acquaintance with new areas of the resource-rich zones of South Asia.

The above synthesis of the material conditions of Megalithic society may help us to comprehend its ideological manifestations also. Although no comprehensive attempt has so far been made to understand the Megalithic religion and ritualism, the basic objective here is to know the role of religion and ritualism as part of ideological system of the Megalithic society. The main source of information invariably are the burials as they form a prominent feature and are crucial in understanding some of the ideological facets of the Megalithic society. A casual survey of the cemetery sites shows that megaliths typically cluster in groups, showing continued use of the same burial area for several centuries. However, it is becoming increasingly clear that the megalithic burial monuments were meant to hold only a very restricted number of persons, and the burial took place in them rather rarely, once or twice in a generation. It is also likely that these burials reflect only a certain (upper?) segment of the society.

It may be contextually useful to recapitulate here the nature of burial practices of the preceding periods, that is of the Neolithic and the Chalcolithic phases. Excavations at many Neolithic, and Chalcolithic sites of South Asia have clearly shown the practice of pit, and urn (kept horizontally, mouth-to-mouth) burial methods for disposing of the dead in primary condition. The dead were buried invariably within the settlement and mostly inside the living premises.

In contrast to this practice, during the Megalithic period in general, the dead were buried outside and away from the settlement area. Both primary and secondary burials occur in this period. The three main sepulchral categories which were in vogue during this period, namely the pit burials, chamber burials, and legged/unlegged urn burials have already been emphasized earlier. Certain structural features such as passage, capstone, porthole, and even menhir (a nonsepulchral monument type) served as interchangeables within the aforementioned tomb types and evolved numerous subvarieties in the course of time.

However, what deserves attention here is the continuation of earlier Neolithic/Chalcolithic burial traditions (but now with a stone appendage over the burial). Leaving aside the sharp differences noticed in the actual treatment of the dead, and also the placement of the remains of the dead in an urn placed verticaly, these two burial methods, namely pit burials and urn burials, strongly indicate continuality of an earlier tradition. That this change was gradual and was definitely an indigenous development can be discerned from some of the earliest Megalithic sites such as Ramapuram, Gandlur, and Piklihal. However, same cannot be said about the chamber burial type. In the event of this being a borrowed mortuary practice, it is not clear whether the advent of this new mortuary element signifies the arrival of new people or was it just a borrowed ritual custom. This important aspect needs further investigation. It is also not clear whether the aforementioned sepulchral types, namely the pit burial, chamber burial, and legged/ unlegged urn burial methods, indicate different ritualistic concepts connected with the burying of the dead or different ethnic groups.

A brief note regarding the occurence of anthropomorphic figures found in association with Megalithic burials may not be out of context here. The occurrence of these anthropomorphic figures in Megalithic sites right from Central Godavari valley to Tamil Nadu Hills is interesting. So far, from at least 15 Megalithic sites these have been reported. The shape and symbolic sculptural features greatly vary in these anthropomorphic figures. However, one striking feature is that they are invariably associated with chamber tombs and dolmens at most of these sites. Although their significance in the cult of the dead is yet to be comprehended, their close association with burial monuments indicates a connection with ancestor worship.

More importantly, a significant shift in the societal attitude toward certain age categories is discernible during the Megalithic period. In the preceding Neolithic/Chalcolithic period, a large number of infant/child burials and comparatively less adult burials are reported. But, as against this fact, in the Megalithic period very few child burials have been noticed and a majority of the burials are of the young-to-mature adults. Infant burials have not at all been found. Even within the adult category, the percentage of adult males is very high which in all probability strongly indicates the patriarchical nature of Mega-lithic society as also the dominant status of its male members.

It has been suggested that ritual activities form an active part of the social construction of reality within social formations and may be conceived as a particular form of the ideological legitimation of the social order, serving sectional interests of particular groups. That the construction of these monumental structures, both sepulchral and nonsepulchral, ultimately depended on the social mobilization of resources and societal cooperation is clearly implied.

Detailed ethnographic studies available for some of the ethnic communities such as Savaras, Gadabas, and Bondos, and Kodis practicing megalithism clearly show that these are closely connected with production-feast-alliance cycle. The occurrence of nonlocal prestige goods in limited number of megalithic burials of superordinate social dimension may suggest the control of long-distance trade by local elite groups, the procurement of which eventually depended on alliance and gift exchange. Thus, burials of superordinate category provide a clue as to how surplus production entered the local cycle of prestige building, embedded as it was in alliances and exchange.

It is also widely noticed that the ritualized chiefly organization of land and lineage through ancestor worship in megalithic tombs is a recurrent phenomenon in different parts of the world and occurs both in small-scale and more developed societies. There is a lack of conceptual studies of this genre for the study area, but these analogs do offer insights into the functional and organizational framework of the Megalithic monuments. If we can understand their functional role, it is quite clear that they do not represent burials as we understand them but may have served as ‘living entities’. The dead were not separated from the living, but lived as ancestors in their houses among the living and could be approached when opening the chamber or contacted through rites and offerings. In this way the megaliths symbolized the collective efforts of the community as also the heroic leadership of ancestor chiefs, legitimizing and sustaining the power of their successors. Thus, ritual and religion clearly served material functions in the social organization of production and the tombs formed part and parcel of the reproduction of power relations.

Significantly, the use of iron in these communities seems to have been limited in its initial phase. It is rightly observed that, in the beginning, the use of iron was mostly confined to the production of weaponry and did not contribute much to handicrafts and agriculture and that the weapons were probably in the sole possession of elites. Iron seems to have started playing a significant and effective role in these areas only after c. 500 BC as there is clear evidence in the increase of agricultural and craftsman’s tools during this phase.

The rise and growth of occupational divisions in these areas seems to have contributed to the beginnings of social differentiation. The aspect of social differentiation and ranking in the Megalithic society is clearly brought out in the analysis of their burial monuments. However, more importantly, the Megalithic society shows a chiefdom-level organization and there are no indications either of a regular taxation system or a regular standing army, which are characteristics of the succeeding state societies.

An augmentation in the intensive field agriculture and greater utilization of mineral resources — as evidenced in the increase of agricultural and craftsman’s tools — seems to be characteristic of the later phase (after c. 500 BC) of the Megalithic society. Probably, rice cultivation acquired new dimension because of improvement in technology, that is, an advance in the production techniques, and this seems to have led to demographic expansion. An increase in the number of sites and colonization of new areas was certainly an outcome of much consequence to the succeeding phases of historical developments.

See also: Asia, South: Baluchistan and the Borderlands; Buddhist Archaeology; Ganges Valley; india, Deccan and Central Plateau; Kashmir and the Northwest Frontier; Neolithic Cultures; Sri Lanka; Civilization and Urbanism, Rise of; Image and Symbol; Political Complexity, Rise of; Ritual, Religion, and Ideology; Social Inequality, Development of.

World History

World History