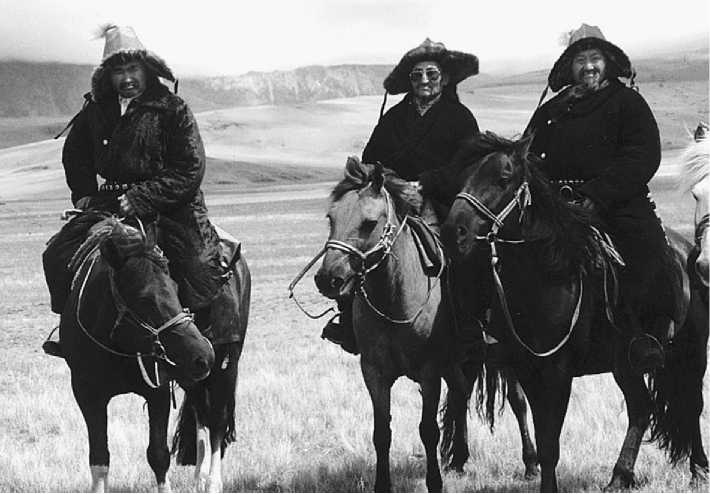

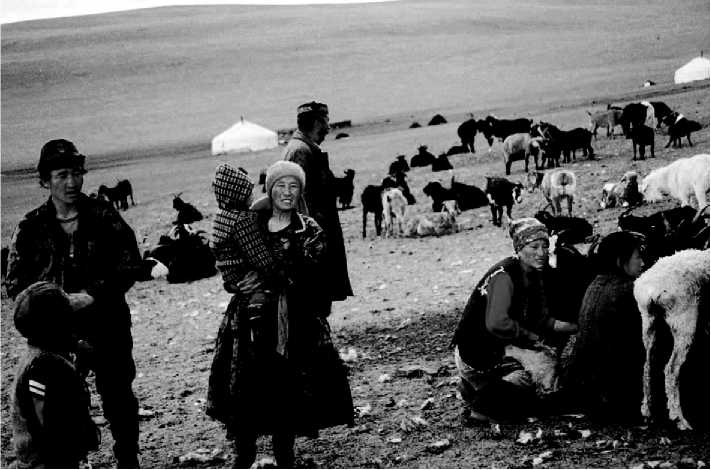

As the drought receded in the steppes, villagers living along the rivers (where their burial mounds are found) returned and more or less simultaneously began experimenting with pastoral nomadism. This entailed driving their herds further into the steppes lands, a mode of life also precipitated by horse riding, which provided greater mobility (Figure 2). Thus, herders returned less frequently to the home base. Innovative portable housing culminated in the yurt (ger in Mongolia), a lattice structure covered on the exterior with heavy felt and lined on the interior walls with colorful carpets, which also covered the floor. By adopting this lifestyle, the population was no longer dependent upon hunting, gathering, and minimal agriculture but rather on their animals - goats, sheep, horses, camels, and, in the higher-altitudes, yak (Figure 3) Their diet consisted primarily of meat, generally sheep - but also horsemeat was prepared for ceremonial occasions - and dairy products, particularly sheep and yak milk, the ceremonial koumiss (fermented mare’s milk), and various cheeses that they

Figure 2 Kazak horseman in the Altai Mountains.

Figure 3 Kazaks at summer pasture in the Altai Mountains with their yurts and herds.

Produced. Tanned leather was fashioned into heavier winter clothing as well as horse accouterments.

On the steppes, nomads may have migrated more than 1000 km during a single year, leaving their winter home in very early spring, moving to a clean, warm locale to lamb-out the herds. A short time later their migration began, generally northward across the steppes, reaching the fulcrum in late spring, and remaining there until the rains of autumn forced them to retrace their route to the winter home. This pattern is also consistent with nomads who migrate into the mountains for summer pasture although the trek may be much shorter - a few up to several hundred kilometers. It has recently been discovered that nomads buried in the Siberian Pazyryk region were infested with hookworm. The closest endemic zones to this infestation were along the shores of the Caspian and Aral seas or in Iran, indicating they had summer migrated over 1200 km.

The shift from a sedentary lifestyle to one of nomadism is noted in the Chowhougou cemeteries located between the Tien Shan foothills and the Taklimakan desert in western China. The earliest rock-lined tombs, located closed to the oasis village, contained a single skeleton whose mortuary items included painted pottery and artifacts relating to a sedentary society. Later dated but similarly constructed tombs in the same cemetery were located closer to the foothills. These, however, held several skeletons. Pottery was coarser and undecorated while offerings now included bronze knives of the type from the Minusinsk Valley in southern Siberia as well as horse accouterments. It would appear that traders on horseback from the northern reaches had made their way through the Tien Shan Mountains to encounter the oasis villages. There they traded bronzes, sheep, and wool for agricultural products and exquisite textiles woven by the oasis women. Before long the younger villagers realized the stress of herding was far less than that of planting and hoeing and soon emulated the northerner nomadism. Nomads normally buried their dead in the summer pasture; here in reverse, they returned to their winter home for the burial ceremony, now placing their deceased in communal pits and including objects from their nomadic lifestyle.

The nomadic winter home and corrals were frequently constructed at the base of a great stone outcropping that provided solar warmth and also protected from the harsh northerly winds that swept the steppes of snow so that some grazing was possible throughout the winter. The home was also in proximity to a small river that provided water and stretches of tall grass along the banks for emergency feed.

Nomads traveled in small support groups, known as auls made up of extended families. Clan and tribal auls commingled at summer and other rites of passage were performed. Tribal alliances were formed as needed for administrative requirements and military expediency as well as for apportioning grazing lands that were never personal property. Under charismatic leadership, confederacies composed of many clans and tribes controlled vast territories. Others, employing large-scale military migrations, created empires (e. g., the Genghis Khanite).

Because of their mobility, military prowess, and ability to rapidly mobilize, nomads had a major

Impact upon bordering sedentary societies. The major tribal alliances of the first millennium BCE, known from Greek, Achaemenid Persian, and other sources, and further identified by Russian archaeology beginning in the late nineteenth century, are known as

(1) the Scythians, occupying southeastern Europe, north of the Black Sea to the lower Don River;

(2) the Sauromatians, whose burials are from the Kuban region east of the Black Sea, along the lower Don and Volga rivers, and throughout the Ural River system; the slightly later (3) Sarmatians, who congregated from the lower Dniester River east, particularly along the Volga and Ural interfluvials. Further to the east, (4) the Saka ranged from central Kazakstan through the Tien Shan Mountains and the Ferghana Valley, northeast through eastern Kazakstan into the Altai Mountains in present-day southern Siberia and Mongolia. All the Early Iron Age nomads spoke variations of Indo-Iranian languages and were ethnically Caucasoids until a Mongoloid admixture was introduced as noted in skeletal material in the central steppes dating from the fourth century BCE, and in southern Kazakstan in the third century BCE. The people now known as the mummies of western China, until at least the fourth century BCE, were also Caucasoids.

The economy of Early Iron Age nomads varied within regions and was dependent upon several factors including climatic conditions as well as the extent of contact between the nomads and their particular sedentary neighbors. As an example, some Scythian tribes in direct contact with Greek colonies north of the Black Sea became sedentary, raising grain for export to the Greek mainland while the Sauromatians and Sarmatians, inhabiting vast stretches of steppe land, increased their wealth by controlling and/or raiding the northerly Silk Routes. The Pazyryk Saka in the Gorny Altai of southern Siberia lived a nomadic lifestyle with minimal migration yet increased their wealth through long-distance trade with the Achaemenid Persian satrapies.

World History

World History