39 Rice, P. (2000). Paleoanthropology 2000—part 1. General Anthropology 7 (1), 11; Zimmer, C. (1999). New date for the dawn of dream time. Science 284, 1243.

Sahul The greater Australian landmass including Australia, New Guinea, and Tasmania. At times of maximum glaciation and low sea levels, these areas were continuous.

Sunda The combined landmass of the contemporary islands of Java, Sumatra, Borneo, and Bali that was continuous with mainland Southeast Asia at times of low sea levels corresponding to maximum glaciation.

Pacific

Ocean

Figure 9.9 Habitation of Australia and New Guinea (joined together with Tasmania as a single landmass called Sahul) was dependent upon travel across the open ocean even at times of maximum glaciations when sea levels were low. This figure shows the coastlines of Sahul and Sunda (Southeast Asia plus the island of Java, Sumatra, Borneo, and Bali) now and in the past. As sea levels rose with melting glaciers, sites of early human habitation were submerged under water.

The Wallace Trench, after Alfred Russel Wallace, who, as described in Chapter 2, discovered natural selection at the same time as Charles Darwin) always separated Sunda and Sahul.

Anthropologist Joseph Birdsell suggested several routes of island hopping and seafaring to make the crossing between these landmasses.172 Each of these routes still involves crossing open water without land visible on the horizon. The earliest known site in New Guinea dates to 40,000 years ago. Sites in Australia are dated to even earlier, but these dates are especially contentious because they involve the critical question of the relationship between anatomical modernity and the presence of humanlike culture. Early dates for habitation of the Sahul indicate that archaic Homo rather than anatomically modern forms possessed the cultural capacity for oceanic navigation. Once in Australia, these people created some of the world’s earliest sophisticated rock art, perhaps some 10,000 to 15,000 years earlier than the more famous European cave paintings.

Interestingly, considerable physical variation is seen in Australian fossil specimens from this period. Some specimens have the high forehead characteristic of anatomical modernity while others possess traits providing excellent evidence of continuity between living Aborigines and the earlier Homo erectus and archaic Homo sapiens fossils from Indonesia. Willandra Lakes— the fossil lake region of southeastern Australia, far from where the earliest archaeological evidence of human habitation of the continent was found—is particularly rich with fossils. The variation present in these fossils illustrates the problems inherent with making a one-to-one correspondence between the skull of a certain shape and cultural capabilities.

Other evidence for sophisticated ritual activity in early Australia is provided by the burial of a man at least 40,000 and possibly 60,000 years ago from the Willandra Lakes region. His body was positioned with his fingers intertwined around one another in the region of his penis, and red ochre had been scattered over the body. It may be that this pigment had more than symbolic value; for example, its iron salts have antiseptic and deodorizing properties, and there are recorded instances in which red ochre is associated with prolonging life and is used medicinally to treat particular conditions or infections. One historically known Aborigine society is reported to have used ochre to heal wounds, scars, and burns. A person with internal pain was covered with the substance and placed in the sun to promote sweating. See this chapter’s Globalscape to learn about the importance of Willandra Lakes to global and local heritage today.

As in many parts of the world, paleoanthropologists conducting research on human evolution in Australia are essentially constructing a view of history that conflicts with the beliefs of Aborigines. The story of human evolution is utterly dependent on Western conceptions of time, relationships established through genetics, and a definition of what it means to be human. All of these concepts are at odds with Aboriginal beliefs about human origins. Still, while conducting their research on human evolution, paleoanthropologists working in Australia have advocated and supported the Aboriginal culture.

While scientists concur that American Indian ancestry can be traced ultimately back to Asian origins, just when people arrived in the Americas has been a matter of lively debate. This debate draws upon geographical, cultural, and biological evidence.

Globalscape

Whose Lakes Are These?

Paleoanthropologists regularly travel to early fossil sites and to museums where original fossil specimens are housed. Increasingly, these same destinations are becoming popular with tourists. Making sites accessible for everyone while protecting the sites requires considerable skill and knowledge. But most importantly, long before the advent of paleoanthropology or paleotourism, these sites were and are the homelands of living people.

Aboriginal people have lived along the shores of the Willandra Lakes region of Australia for at least 50,000 years. They have passed down their stories and cultural traditions even as the lakes dried up and a spectacular crescent-shaped, wind-formed dune (called a lunette) remained. The Mungo lunette has particular cultural significance to three Aboriginal tribal groups. Several major fossil finds from the region include cremated remains as well as an ochred burial, both dated to at least 40,000 years ago. Nearly 460 fossilized footprints dated to between

19,000 and 23,000 years ago were made by people of all ages who lived in the region when the Willandra Lakes were still full of water. How can a place

Of local and global significance be appropriately preserved and honored?

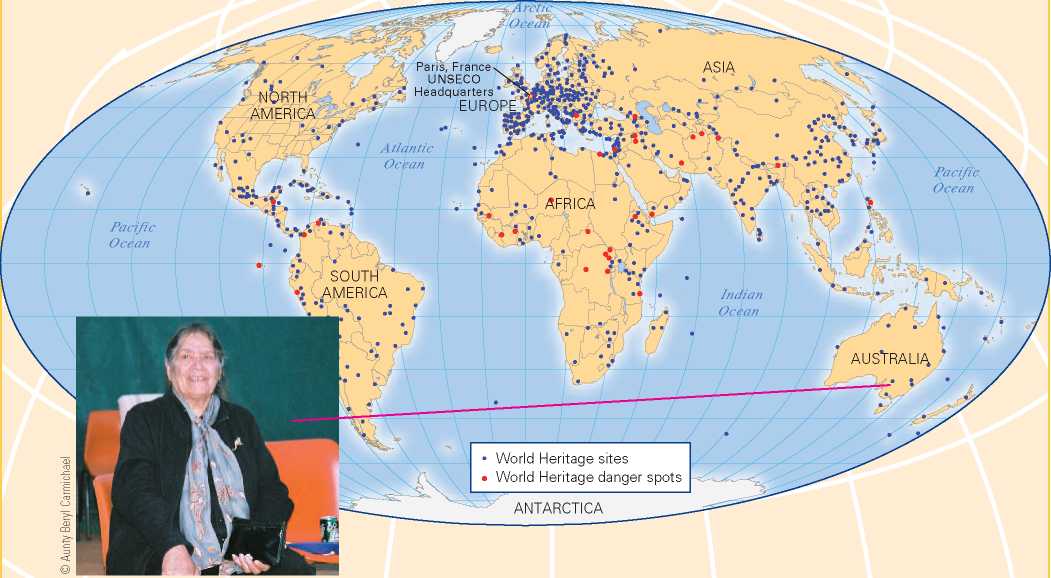

Since 1972, UNESCO's World Heritage List has been an important part of maintaining places like Willandra Lakes, which was itself inscribed as a World Heritage Site in 1981. Individual states apply to UNESCO for site designation, and if approved they receive financial and political support for maintaining the site. When designated sites are threatened by natural disaster, war, pollution, or poorly managed tourism, they are placed on a danger list, indicated with a red dot on the map above, forcing the local governments to institute measures to protect the sites in order to continue receiving UNESCO support.

Each year approximately thirty new World Heritage sites are designated. In 2009 the list includes 890 properties: 176 natural preserves, 689 cultural sites, and 25 mixed sites. Fossil and archaeological sites are well represented on the World Heritage List. The Willandra Lakes site is recognized for both natural and cultural values.

While important to the world community, Willandra Lakes has particular meaning to the Aborigines. Aunty Beryl Carmichael, an elder of the Ngiyaampaa people, explains that this land is integrated with her culture:

Because when the old people would tell the stories, they'd just refer to them as "marrathal warkan,” which means long, long time ago, when time first began for our people, as people on this land after creation. We have various sites around in our country, we call them the birthing places of all our stories.

And of course, the stories are embedded with the lore that governs this whole land. The air, the land, the environment, the universe, the stars.®

Not only are Aunty Beryl's stories and the land around Willandra Lakes critical for the Ngiyaampaa and other Aboriginal groups, but their survival ultimately contributes to all of us.

On the next page are listed the sites considered endangered at the June 2009 meeting of the World Heritage Committee. Committee members included representatives from countries throughout the globe including: Australia, Bahrain, Barbados,

Brazil, Canada, China, Cuba, Egypt, Israel, Jordan, Kenya, South Korea, Madagascar, Mauritius, Morocco, Nigeria, Peru, Spain, Sweden, Tunisia, and the United States.

Globalscape

Peru

Chan Chan archaeological zone (1986)

Philippines

Rice terraces of the Philippine Cordilleras (2001)

Senegal

Niokolo-Koba National Park (2007)

Serbia

Medieval monuments in Kosovo (2006)

Tanzania

Ruins of Kilwa Kisiwani and ruins of Songo Mnara (2004)

Venezuela

Coro and its port (2005)

Yemen

Historic town of Zabid (2000)

Global Twister The listing of endangered sites brings global pressure on a state to find ways to protect the natural and cultural heritage contained within its boundaries. Do you think this method of global social pressure is effective?

A Australian Museum Archives.

Http://australianmuseum. net. au/movie/

Why-the-stories-are-told-Aunty-Beryl

These Word Heritage Sites in Danger are

Afghanistan

Cultural landscape and archaeological remains of the Bamiyan Valley (2003) Minaret and archaeological remains of Jam (2002)

Belize

Belize Barrier Reef reserve system (2009)

Central African Republic

Manovo-Gounda St. Floris National Park (1997)

Chile

Humberstone and Santa Laura Saltpeter Works (2005)

Colombia

Los Katios National Park (2009)

Cote d’Ivoire

Comoe National Park (2003)

Mount Nimba Strict Nature Reserve (1992)

Democratic Republic of the Congo

Garamba National Park (1996) Kahuzi-Biega National Park (1997) Okapi Wildlife Reserve (1997)

Salonga National Park (1999)

Virunga National Park (1994)

Ecuador

Galapagos Islands (2007)

Indicated with a red dot on the preceding page. Egypt

Abu Mena (2001)

Ethiopia

Simien National Park (1996)

Georgia

Historical Monuments of Mtskheta (2009)

Guinea

Mount Nimba Strict Nature Reserve (1992)

India

Manas Wildlife Sanctuary (1992)

Iran

Bam and its cultural landscape (2004)

Iraq

Ashur (Qal'at Sherqat) (2003)

Samarra archaeological city (2007)

Jerusalem (site proposed by Jordan)

Old City of Jerusalem and its walls (1982)

Niger

Air and Tenere Natural Reserves (1992)

Pakistan

Fort and Shalamar Gardens in Lahore (2000)

The conventional wisdom has long been that the first people migrated into North America over dry land that connected Siberia to Alaska. This so-called land bridge was a consequence of the buildup of great continental glaciers. As these ice masses grew, there was a worldwide lowering of sea levels, causing an emergence of land in places like the Bering Strait where seas today are shallow. Thus Alaska became, in effect, an eastward extension of Siberia (Figure 9.10). Climatic patterns of the Ice Age kept this land bridge, known as Beringia or the Bering Land Bridge, relatively ice free and covered instead with lichens and mosses that could support herds of grazing animals. It is possible that Upper Paleolithic peoples could have come to the Americas simply by following herd animals. The latest genetic evidence indicates movement took place back and forth across Beringia.

According to geologists, conditions were right for ancient humans and herd animals to traverse Beringia between 11,000 and 25,000 years ago. Though this land bridge was also open between 40,000 and 75,000 years ago, there is no evidence that conclusively confirms human migration at these earlier dates. As with the Sahul, early dates open the possibility of spread to the Americas by archaic Homo.

Although ancient Siberians did indeed spread eastward, it is now clear that their way south was blocked by massive glaciers until 13,000 years ago at the earliest.173 By then, people were already living further south in the Americas. Thus the question of how people first came to this hemisphere has been reopened. One possibility is that, like the first Australians, the first Americans may have come by boat or rafts, perhaps traveling between islands or ice-free pockets of coastline, from as far away as the Japanese islands and down North America’s northwestern coast. Hints of such voyages are provided by a handful of North American skeletons (such as Kennewick Man) that bear a closer resemblance to the aboriginal Ainu people of northern Japan and their forebears than they do to other Asians or contemporary Native Americans. Unfortunately, because sea levels were lower than they are today, coastal sites used by early voyagers would now be under water.

Securely dated objects from Monte Verde, a site in south-central Chile, place people in southern South America by 12,500 years ago, if not earlier. Assuming the first

Figure 9.10 The Arctic conditions and glaciers in northeastern Asia and northwestern North America provided opportunity and challenges for ancient people spreading to the Americas.

On the one hand, the Arctic conditions provided a land bridge (Beringia) between the continents, but on the other hand, these harsh environmental conditions posed considerable challenges to humans. Ancient people may have also come to the Americas by sea. Once in North America, glaciers spanning a good portion of the continent determined the areas open to habitation.

Populations spread from Siberia to Alaska, linguist Johanna Nichols suggests that the first people to arrive in North America did so by 20,000 years ago. She bases this estimate on the time it took various other languages to spread from their homelands—including Eskimo languages in the Arctic and Athabaskan languages from interior western Canada to New Mexico and Arizona (Navajo). Nichols’s conclusion is that it would have taken at least 7,000 years for people to reach south-central Chile.174 Others suggest people arrived in the Americas closer to 30,000 years ago or even earlier.

A recent genetic study using mtDNA indicates that two groups of migrants crossed Beringia between 15,000 and 17,000 years ago but then took different paths. One group traveled down the Pacific Coast and the other down the center of the continent. While the dates generated in this study are as early as others have suggested, these findings support the notion that distinct language groups made separate migrations.

The picture currently emerging, then, is of people, who may not have looked like modern Native Americans, arriving by boats or rafts and spreading southward and eastward over time. In fact, contact back and forth between North America and Siberia never stopped. In all probability, it became more common as the glaciers melted away. As a consequence, through gene flow as well as later arrivals of people from Asia, people living in the Americas came to have the broad faces, prominent cheekbones, and round cranial vaults that tend to characterize the skulls of many Native Americans today. Still, Native Americans, like all human populations, are physically variable. The Kennewick Man controversy described in Chapter 5 illustrates the complexities of establishing ethnic identity based on the shape of the skull. In order to trace the history of the peopling of the Americas, anthropologists must combine archaeological, linguistic, and cultural information with evidence of biological variation.

Although the earliest technologies in the Americas remain poorly known, they gave rise in North America, about 12,000 years ago, to the distinctive fluted spear points of Paleoindian hunters of big game, such as mammoths, mastodons, caribou, and now extinct forms of bison. Fluted points are finely made, with large channel flakes removed from one or both surfaces. This thinned section was inserted into the notched end of a spear shaft for a sturdy haft. Fluted points are found from the Atlantic seaboard to the Pacific Coast, and from Alaska down into Panama. The efficiency of the hunters who made and used these points may have hastened the extinction of the mammoth and other large Pleistocene mammals. By driving large numbers of animals over cliffs, they killed many more than they could possibly use, thus wasting huge amounts of meat.

Upper Paleolithic peoples in Australia and the Americas, like their counterparts in Africa and Eurasia, possessed sophisticated technology that was efficient and appropriate for the environments they inhabited. As in other parts of the world, when a technological innovation such as the fluted points begins, this technology is rapidly disseminated among the people inhabiting the region.

World History

World History