The Pacific Coast of Canada and the United States was occupied by a continuous fabric of affluent, fishing-oriented cultures. Farther inland on the prairie, one found the bison hunting tribes. In between—in other words, between the coast and the prairie—lived people who specialized in the mountain and desert ecologies that stretched from the Cascade and Sierra Nevada Mountain ranges in the north to the Mojave Desert in present-day Nevada. The three parallel cultural zones were clearly all in trade contact with one another but, in battles or in other types of contestations, the mountain and desert people were on a weaker footing.

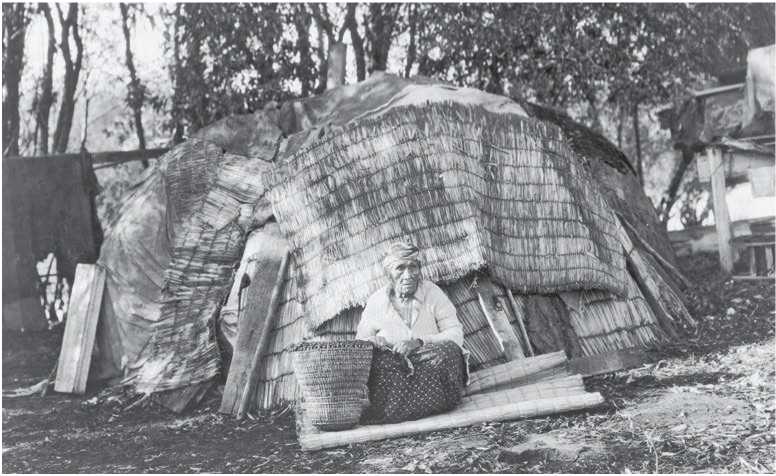

In the United States, one of the more important of the desert cultures were the Paiute. The origin of the word is not known. The northern Paiute called themselves Numa, while the southern Paiute refered to themselves as Nuwuvi. Both terms mean “the people.” They constructed round brush shelters; gathered seasonal seeds, grasses, and roots; collected insects, larvae, and small reptiles; and hunted antelope, deer, rabbits, and other small mammals. Agave, a small spineless mountain cactus that grows during spring, was roasted to produce a sweet, chewy substance. The flowers, leaves, stalks, and even the sweet sap are all consumable. The leaves of several also yield enough fiber for baskets (Figure 5.33).

More sedentary were the Klamath, who lived in the area of modern-day Oregon around the Upper Klamath Lake and the Klamath, Williamson, and Sprague rivers. They called themselves maqlaqs, meaning “people.” They lived primarily on fish, but they also collected roots, such as those of the water lilies, and various nuts and berries. The men hunted deer, antelope, and other small mammals in the forests. The men wore buckskin breechcloths, while the women wore aprons of buckskin along with woven, basketlike hats.

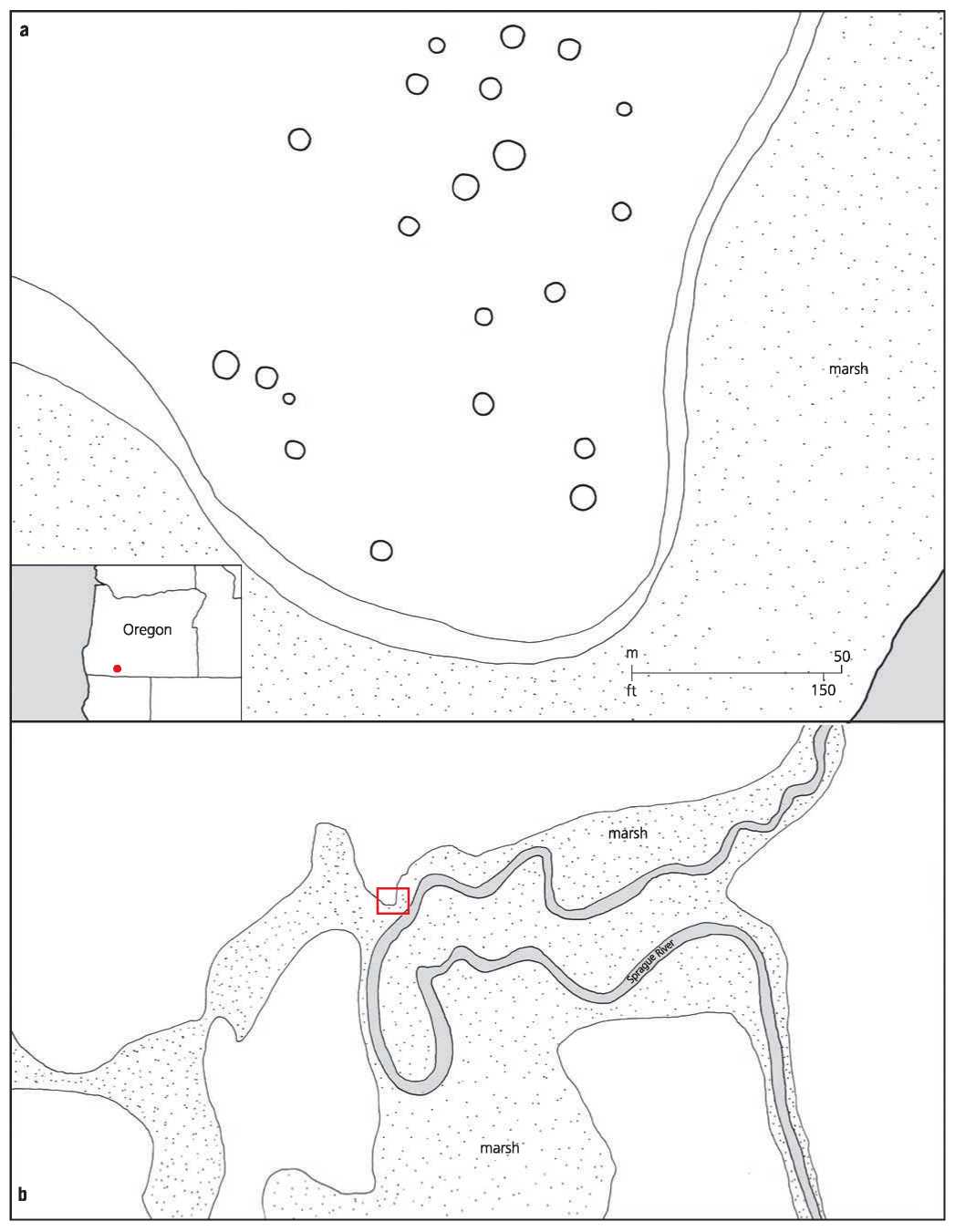

The ancestors of the Klamath began to settle in the region as early as 5000 bce. The villages were usually situated on a terrace above the river. They were also usually close to a place in the river that did not freeze during the winter season, such as near springs or at the confluence of a feeder streams. The villages were not tightly organized and perhaps were not in that sense villages, but an extended clan community. The pattern of the structure of the houses shows a generally circular floor plan slightly elongated on the north-south axis. Floors were not flat but in the shape of a shallow saucer. Most of the houses, as is typical of the pit house tradition, have a bench or shelf set a short distance up from the floor and running around the perimeter of the house. Since there seem to be few postholes, the roof was probably a conical structure of lightweight branches and grass mats.31 Several sites were located on the higher north bank of

Figure 5.33: Klamath hut, Oregon, 1923. Source: Edward Curtis Collection, Prints & Photographs Division, Library of Congress, LC-USZ62-118931

Figure 5.34a, b: Sprague River site, Oregon: (a) plan, (b) site. Source: Timothy Cooke/L. S. Cressman, "Klamath Prehistory," Transactions of the American Philosophical Society 46 (1956): 434

The Sprague River (Figure 5.34a, 5.34b). In spring, mountain melt expands the river to create a chain of broad marshes, to which the Klamath were perfectly adapted.

The Klamath also used a more traditional winter pit house with the usual four posts and a roof of grass mats laid in horizontal courses, with dirt thrown over the grass and mats to form a tight covering. Most houses opened toward the southeast and were divided according to the usual cosmological pattern.32

Mount Shasta, standing 4,200 meters above the surrounding valleys, rises just to the south of the Klamath area. It casts a gigantic shadow at sunrise and is visible for hundreds of miles. It was a territorial boundary for four Native American peoples—the Shasta, Modoc, Ajumawi/ Atsuwegi, and Wintu—all of whom revere the mountain as being at the center of creation. Each year, even today, the remnants of the Wintu tribe invoke the mountain’s spirit with ritual dances that ensure the continued flow of the sacred springs. The Shasta people believed that the Great Spirit flrst created the mountain by pushing down ice and snow through a hole from heaven, then used the mountain to step onto the earth. He created trees and called upon the sun to melt snow to provide rivers and streams. The mountain spirit breathed on the leaves of the trees and created birds to nest in their branches. He broke up small twigs and cast them into streams, where they became flsh; branches cast into the forest became animals. Shamans, usually women, played an important role in coming to terms with these spirits. They acquired their powers through dream trances during which a spirit teaches the shaman its song. The song could then be intoned to remove pain from the sick, but it could also be invoked to bring about the death of an enemy.33

World History

World History