In the Semirechiye (Seven Rivers) in southern Kazakstan, large stone-covered kurgans measuring up to 100 m in diameter are represented by those constructed in the Chilikta Valley and at Issyk just

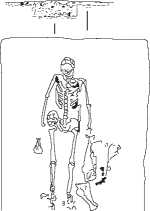

(a)

Figure 9 Tasmola burials in western Kazakstan.

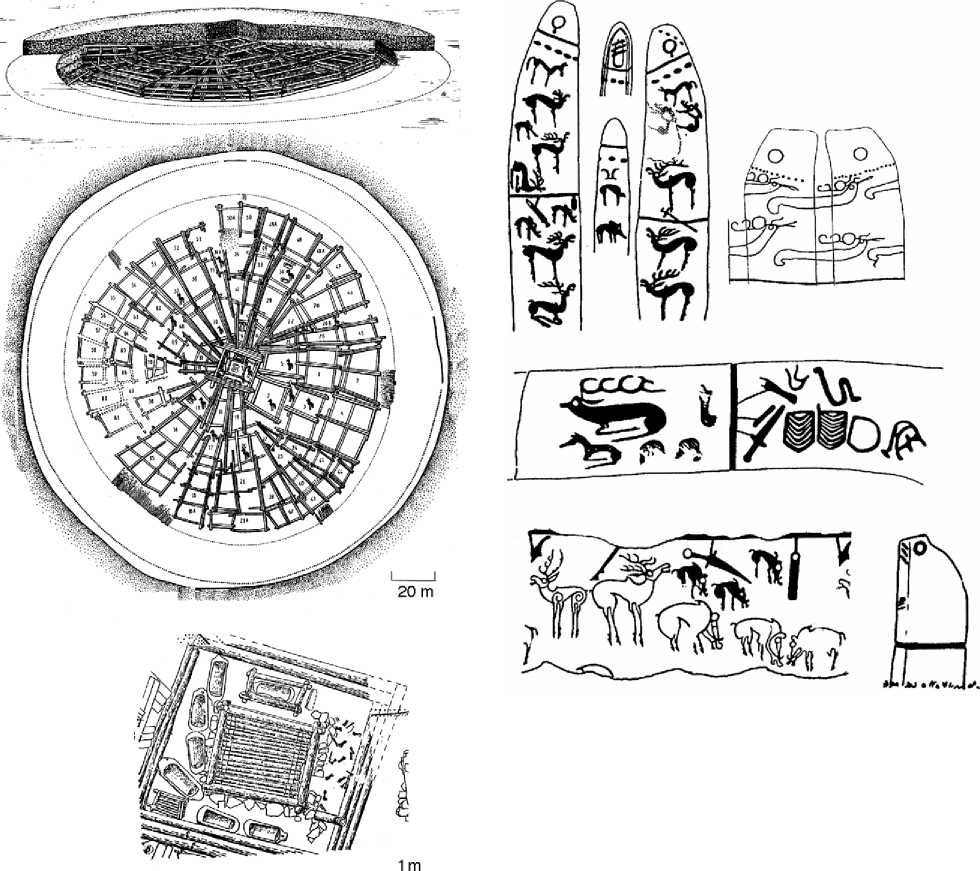

Figure 11 Various styles of olenniye kamni associated with the Arzhan Kurgan.

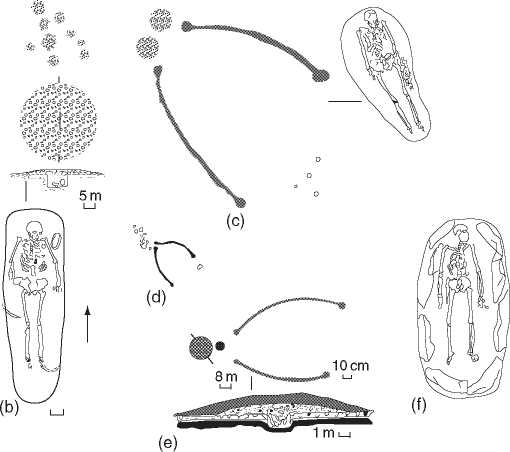

Figure 10 Schematic and details of the Arzhan Kurgan.

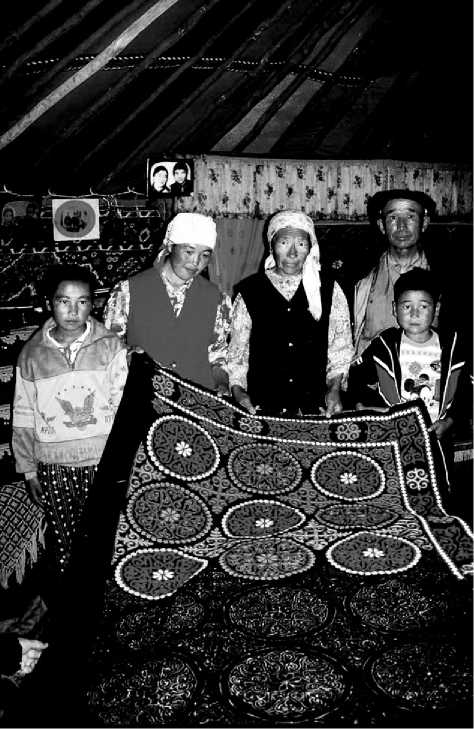

North of Almaty. These yielded prolific Animal Style iconography wrought in gold and frequently decorated with semiprecious stones. Women also played prominent roles in this nomadic society particularly in religious or cultic matters, an influence transmitted into western China (Figure 12). Burial rituals while constructing the large kurgans often included feasting, particularly on horsemeat cooked in large cauldrons.

Bronze Age anthropomorphic fertility dancers recorded in stone at Kangjiashimenji in western China give way to sun gods and Early Iron Age Shamanic images of ritual horned horses and the ubiquitous zoomorphisms at sites such as Tamgaly near Almaty, Kazakstan, and Saimaly Tash in the Kyrghyz Tien Shan (Figure 13).

Oases cemeteries at Chowhougou at the northern edge of the Taklimakan Desert and the base of the

Tien Shan Mountains reveal that nomadism was introduced into the high Tien Shan c. 900 BCE when multiple burials replaced a single interment. During the Bronze Age the deceased had been placed on the right side in a flexed position but this custom soon changed to the typical Early Iron Age supine position. Horse harnessing, including snaffle bits of a type from southern Siberia, was added to the list of grave goods and crude pottery was substituted for the villagers’ fine painted ware. Bronze-casting techniques were introduced into western China at this time, probably from smithies known to have had workshops east of the Ural Mountains or in the southern Siberian Minusinsk Valley. The sophisticated cast-bronze artifacts from the Semirechiye and the Tarim Basin included altars and immense cauldrons, mirrors, knives, whetstone handles, and horse accouterments. Around 400 BCE, burials ceased at Chowhougou, possibly signaling that the Saka were being forced from their territories by the Hsiung-nu and Yiieh Chih confederacies.

Burnished gray pottery from oasis cemeteries near Hami along the eastern Taklimakan Desert reflects

Figure 12 Contemporary Kazak nomads in theiryurt in western China.

Pottery styles and techniques from northeastern Iran, suggesting population incursion from that region. Caucasoid mummies, dressed in finely woven woolen fabrics, have been excavated from cemeteries south of the Taklimakan Desert. The quality of the textiles suggests that the villagers traded wool from nomads living in higher elevations where the animals produce finer quality wool than they can in the intense desert heat. Artifacts associated with several female mummies also indicate a cultic belief system similar to that practiced by the Saka.

World History

World History