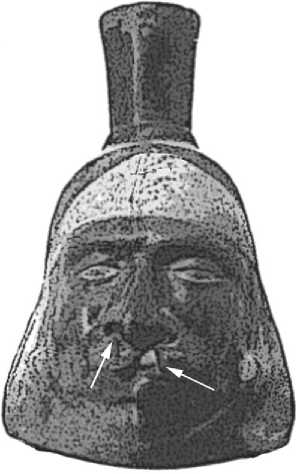

Archaeoparasitologists find their data in a variety of archaeological contexts. Historical medical texts provide information about ancient parasitological knowledge and treatment. Artifacts provide rare glimpses of the pathology caused by certain parasites. For example, potters of the Peruvian Moche culture portrayed the facial disfigurement resulting from Leishmania infection (Figure 7). This protozoan parasite can cause destruction of the soft and hard tissue of the face.

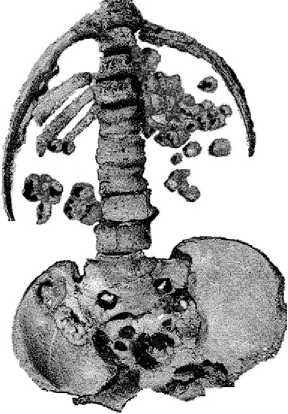

Skeletal remains can reveal hard tissue pathology caused by parasites. Calcification of soft tissue of the urinary tract often results from Schistosoma hemato-bium (blood fluke) infection. Cysts of the tapeworm Echinococ cus granulosis calcify and are preserved in burials (Figure 8). Destructive bone lesions resulting from Leishman ia infection are evident in skeletal remains from Peru (Figure 9). Sediments such as soil within burial pelvic girdles (see Burials : Dietary Sampling Methods) are an important source of

Figure 7 Moche ceramics depict facial lesions consistent with the pathology caused by one form of the protozoan Leishmania brasiliensis which is transmitted by a sand fly vector.

Figure 8 This is a drawing of hydatid cyst disease excavated from Medieval Denmark. Hydatid disease is caused by a parasitic infection by a tapeworm of the genus Echinococcus. The brown nodules are the mineralized cysts cause by the tapeworm larvae.

Information about parasites. For example, German researchers were able to recover liver fluke (Fasciola hepatica) from the sediment of human and cattle pelvic girdles. This showed that this debilitating parasite was a threat to humans and their domestic livestock.

Mummies preserve the hard tissue and soft tissue pathology caused by parasites as well as the parasites themselves. Ectoparasites such as fleas, head lice, body lice, and crab lice are easily recovered from

Figure 9 This pathology from a skeleton in Peru could be the result of infection with Leishmania brasiliensis. (Reprinted with permission from Memorias do Instituto Oswaldo Cruz.)

Mummies and the clothing buried with mummies. Parasites of the lungs, intestinal tract, liver, and urinary tract are evident. Molecular biological diagnosis can recover the DNA of ancient parasites from mummified tissue, even when the parasites themselves have decomposed. Therefore, each mummified corpse is extremely important in the analysis of parasitic diseases. Also, mummified animals are a wonderful source about parasites that may have threatened the vitality of domestic animals.

In the twentieth century, coprolites provided most of the information about parasitic disease. The eggs and larvas of parasites that disperse their offspring are easily found in coprolites. However, Bain describes the increasing importance of analysis of domestic archaeological sediments in archaeoparasit-ology. Sediments from latrines, sewers, drains, streets, yards, and living floors contain parasite eggs. Parasites were so abundant in medieval and colonial villages that hundreds of parasite eggs per milliliter of house sediments are commonly found. In latrines, drains, and sewers, the numbers of eggs range into hundreds of thousands per milliliter of sediment. The analysis of sediments from domestic context will be increasingly important in the future.

The microscope is the main tool of the archaeopara-sitologist. Most diagnoses of helminths and arthropods have been made with compound or binocular microscopes. However, molecular biology and enzyme diagnostic methods have expanded the range of parasites identified from archaeological sites. Enzyme-linked immunoassay is a new, proven method for the identification of parasite antigens that can be applied To coprolites, mummies, and all types of archaeological sediments. So far, protozoa have been effectively diagnosed. This is very important because protozoa cysts are ephemeral in archaeological remains and are only rarely found with the microscope. Molecular biological characterization of ancient parasite DNA is very useful in making definitive diagnosis of ancient parasites and identifying genetic strains of a single species.

The power of modern archaeoparasitology is based on its ability to quantify infections for comparative evaluation of disease. There are a variety of methods for quantification of eggs per milliliter or gram of archaeological sediments and coprolites. These include dilution methods derived from clinical techniques and concentration methods derived from palynological techniques. Quantifying eggs allows comparative evaluation of parasitism between sites and features within sites.

World History

World History