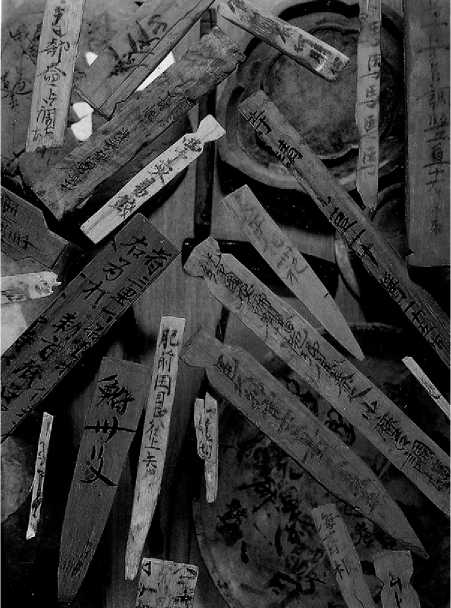

Sources utilized by East Asian historical archaeology have affected its interpretations and conclusions. Written sources vary from transmitted texts such as the second century BCE Shiji (Sima Qian’s Records of the Historian) that have circulated since first produced, to archaeologically recovered records such as wooden slips dating to the seventh and eighth centuries and discovered in twentieth-century excavations of ancient Japanese capitals (Figure 1). How literary sources have come through time and the material on which they are recorded affects their reliability and completeness, and therefore their uses by historical archaeologists. Before the development of mass

Figure 1 Wooden tablets recovered from excavations at Nara Palace, Nara, Japan.

Printing techniques, hand-copying ensured that circulating texts existed in different editions or were altered through copyist’s error, while cast bronze inscriptions have survived without distortion. In China, the First Emperor of Qin’s destruction in 213 BCE of all philosophical works and histories not sanctioned by the state drastically reduced the availability of pre-Qin records. Without a doubt, scientifically excavated archaeological finds in twentieth and twenty-first century have greatly supplemented the quantity and character of historical data available for consultation throughout East Asia.

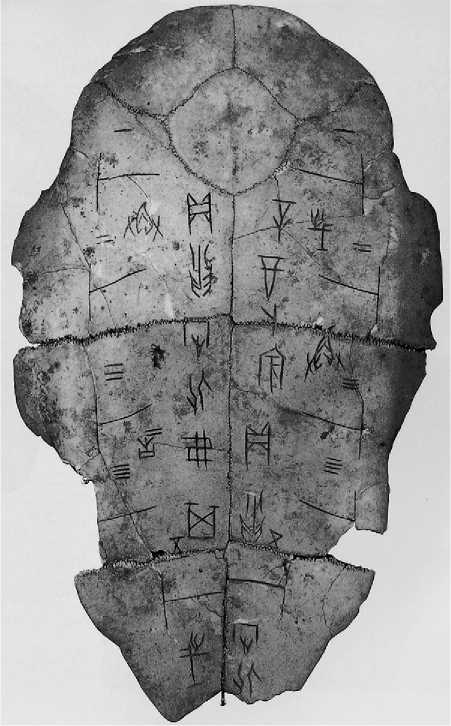

Chinese written sources are the oldest in East Asia. Marks on Yangshao period pottery (c. 5000 BCE) in north China are not considered true writing, but at several sites in eastern China, including Taosi in Shanxi, Dinggong in Shandong, and Longqiuzhuang in Jiangsu, pottery of c. 2000 BCE bears strings of character-like marks that, while still undeciphered, more closely resemble true writing and may represent the beginnings of literacy. East Asia’s first decipherable writing comes from late Shang period (c. 12001045 BCE) eastern China. ‘Oracle bones’ - prepared turtle plastrons and cattle scapulae - used for divination by the late Shang kings were found at the Yinxu site in Anyang, Henan (Figure 2). These bear characters incised prior to pyromantic divination which cracked the bones. Of the 5000 characters identified to date, 40% can be read, and record the divination and its response. Names and brief inscriptions are also cast onto bronze ritual vessels of the same period. In the Western Zhou period (1145-771 BCE), such inscriptions become longer and more frequent, producing what Jessica Rawson has called ‘‘memorials of political events and social relationships essential to the structure of Zhou government and society’’. Some Shang jades also bear brush-written characters, implying other unpreserved media and tools of writing for the Shang and Western Zhou periods. The first surviving examples of brush-writing on bamboo and wooden slips come from archaeological contexts of the Eastern Zhou period (770-222 BCE), primarily tombs. Inscribing records on stone and brushwriting on silk also began during this time. Written documentation multiplied with the bureaucratically organized government of the Han Empire (202 BCE-CE 220), but texts are still fragmentary. Paper was invented in the Eastern Han dynasty (25-220) and used for writing, painting, and making rubbings of inscribed stone tablets, which was the earliest form of copying before invention of woodblock printing during the Tang Dynasty (618-907) allowed mass production. While the keeping of dynastic histories started in the Han, it was not until the

Figure 2 Turtle plastron ‘oracle bone’ with incised characters from excavations at Yinxu, Henan Province, China.

Song Dynasty (960-1276) that preservation and commercial developments conspired to provide an explosion in the amount of source material for the historical record.

The first textual references to either Korea or Japan come from Chinese histories, the Wei Shu (Wei History), a section of the Sanguo Zhi (History of the Three Kingdoms) dated 280, and the Hou Han Shu (History of the Later Han), compiled between 398 and 445. These accounts are limited, but as Gina Barnes writes, they are ‘‘intentional ethnographic reconnaissance by embassies of the Han court’’, and provide much information about cultures and peoples that can complement the archaeological record of development and change.

Korea’s earliest extant records consist of archaeologically recovered wooden tablets used for recordkeeping in the Silla period (c. 300-668) and two transmitted texts, the twefth-century Samguk Sagi (History of the Three Kingdoms) and the thirteenth-century Samguk Yusa (Memorabilia of the Three

Kingdoms), both compiled from earlier records no longer extant. Traditional historical understandings rest on the Samguk Sagi’s dates for the formation of Koguryo, Silla, and Paekche in the first century BCE, but archaeology is challenging this view. A new text, the purportedly eighth-century Hwarang Segi (Annals of Hwarang), was recently discovered, but scholarly debate continues about its veracity.

Japan’s earliest extant records are also archaeologically recovered wooden tablets used for recordkeeping in the early capitals in the Kinai region, and two transmitted texts, the eighth-century court chronicles, the Kojiki (Record of Ancient Things), dating to 712 and the Nihon Shoki (The Chronicles of Japan) of 720. These two books, also complied from earlier nonextant documents, are the sources for the idea of an unbroken historical succession of divine emperors extending back to the mythological past.

Excavated and transmitted artifacts, such as images on bronze, pottery and porcelain vessels, tomb walls, pottery figurines and models, sculpture, textiles, and later ink and watercolor paintings with images of the court and daily life; cosmology; clothing; and even leisure activities also supplement written texts with very important evidence for the understanding of past activities and beliefs in China, Korea, and Japan.

World History

World History