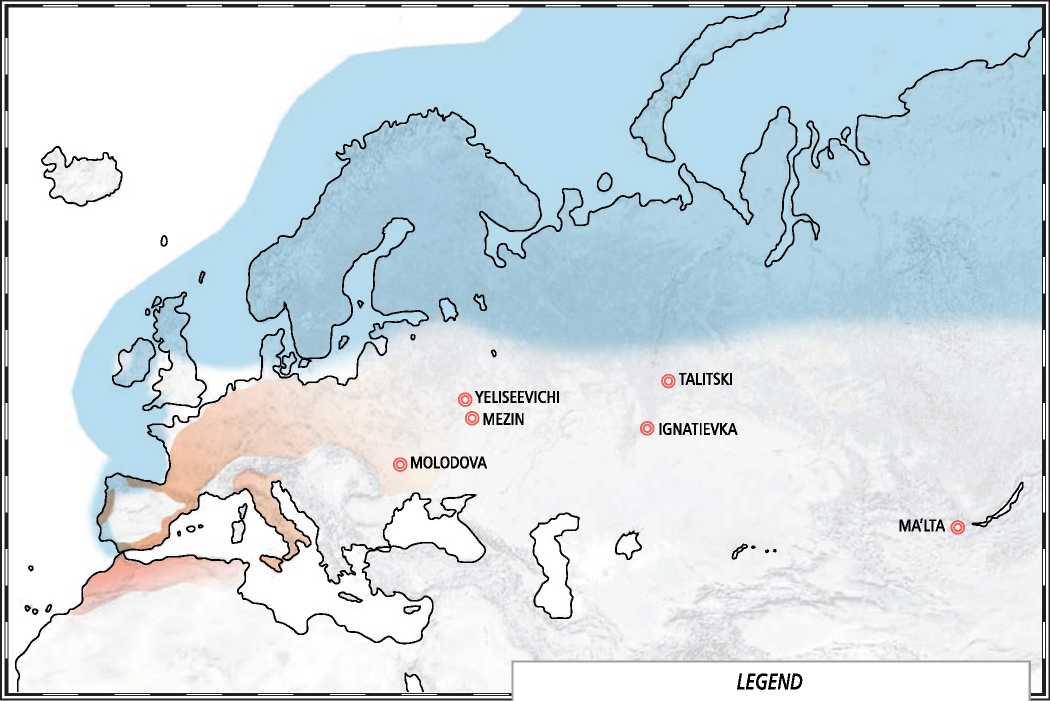

Back in Europe, with the warming of the climate, a new ecological world began to take shape. Forests now provided cover for the expansion and diversification of smaller animals and plant foods. The larger animals were still present but only in the residual pockets of northern steppe. The human diet thus came to included birds and small game in combination with plant-derived food. Rivers provided a constant fish supply. With this change we see the emergence in France and Spain of a new tradition that though built on Gravettian-era principles came to have its own distinctive set of characteristics. It is known as the Magdalenien Culture (16,000-8000 bce) (Figure 2.19). The Magdaleniens produced excellently crafted flint tools, elaborately worked bone implements, elegant Venus figurines, and numerous items of

Figure 2.19: Magdalenien and Ibero-Maurusian cultures (15,000 to 9000 bce). Source: Florence Guiraud

MAGDALENIEN CULTURE I IBERO-MAURUSIAN CULTURE

CAPSIAN CULTURE PALEOLITHIC SITES

Figure 2.20: Magdalenien culture ivory horse sculpture, France. Source: ©Guerin Nicolas (Http://creativecommons. org/ licenses/by-sa/3.0/deed. en)

Personal adornment (Figure 2.20). A comparison of artifacts found in Gravettian and Mag-dalenien sites, such as Abri de la Madeleine, France, shows that whereas almost nothing from a Gravettian site came from more than 200 kilometers away, a small but significant percentage of material found at the Magdalenien sites came from much farther away thus indicating the presence of a burgeoning trade economy.25 Mediterranean shells, for example, which were used for status or barter, appear for the first time in far-ofi' central Germany.

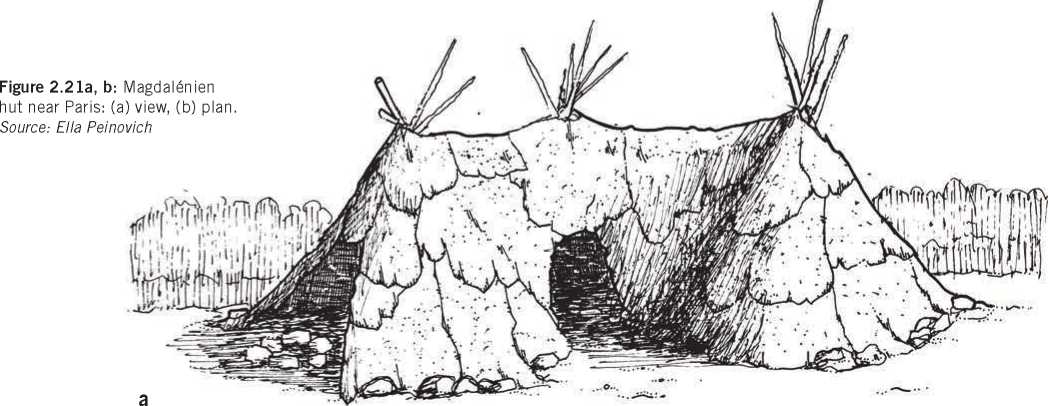

Settlements were composed of sturdy cone-shaped structures, about 3 meters in diameter, consisting of poles tied at the top with leather cords and anchored at their base by rocks. A fire pit was located sometimes in the center and sometimes outside near the entrance. One tent, about 30 meters long, contained three living units each with its own hearth. Small heaps of ochre were found around the hearths. Most of the other tents are circular or oval, about 3 meters in diameter.26 Similarities to the Gravettians are obvious. But whereas Gravettians built camps, the Magdalenien because of their affluence, could create large settlements. In the Paris Basin, 80 kilometers upstream from Paris along the Seine River remains have been uncovered at Pincevent of a 3500-square-meter settlement of over one hundred huts (Figure 2.21a and 2.21b). It was close to a flat shore section of the stream that served as a reindeer crossing and that was thus a good hunting spot during the migrations from late summer to the end of autumn.

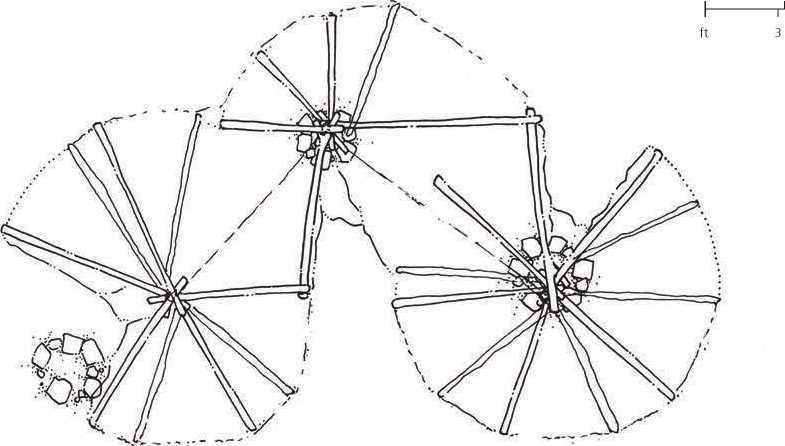

Figure 2.22: Magdalenien era caves in southern France and northern Spain. Source: Florence Guiraud

Portable Venus figurines continue to be important, but the Magdalenien Culture provides the first clear evidence that spiritual practices were becoming spatialized and intensified. It was in their caves that they truly excelled, developing them into regional cult centers. The caves had, of course, begun to be painted already during the Gravettian period, but with the Magdaleniens their significance was much enhanced. They were designed as places of mystery and initiation (Figure 2.22). Even today, these caves evoke the feeling of

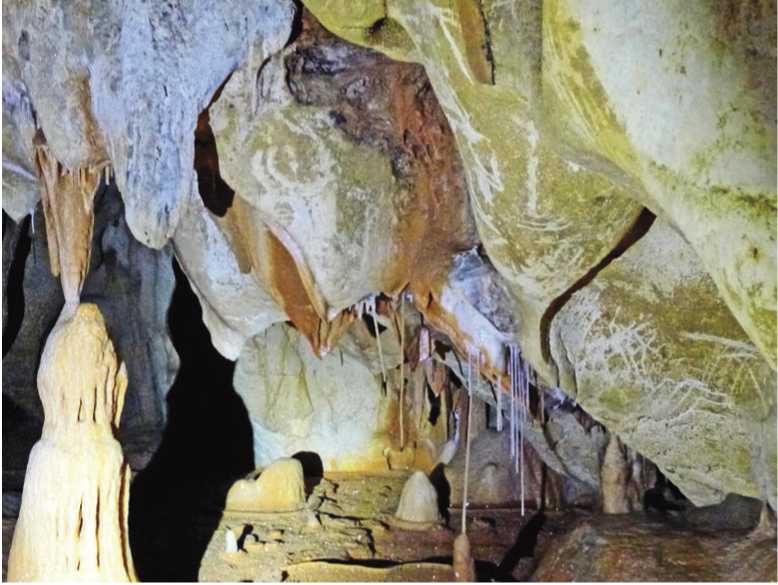

Otherworldliness.27 The grottos of Gargas, Chavet, Cussac Cave, Pech Merle, and Bedeilhac have within them springs that drip from the ceilings, odd-shaped stalactites and stalagmites, as well as columns, cavities, rooms, domes, vaults, passages, fissures, and dripholes, ofi:en glistening, shimmering, and sparkling in the light of oil lamps (Figure 2.23). Several caves have rivers running through them. The overall impression is of places that are dynamic and animated. The drawings of animals, lines, dots, rectangles, and checkerboard patterns on the walls of these caves only elevate that feeling.

One of the most important of the cave complexes was at Lascaux, France, from about

Figure 2.23: Chauvet Cave, France. Source: Jean Clottes

15,000 BCE, where along its 140 meter length we see hundreds of drawings of animals, including a bull with sharp, curving horns and a powerful rump, a group of restless horses, and a charging bison. The Altamira Cave in northern Spain shows a herd of bison in difierent poses. In some places along the cave wall, the painter even exploited the natural contours of the rock to create three-dimensional efiects. Even though some of the drawings were done by individuals, others obviously required the labor of several people, especially the drawings that were made on a gigantic scale or at heights many meters above the cave floor, requiring scafiolding. At Labastide in the Pyrenees, an immense horse is depicted 5 meters above the floor level. At Bernifal in the Dordogne in France, mammoths are painted 7 meters up. In all these places, skilled crafi:smen were at work, people who learned the art and who must certainly have passed it on from generation to generation. We know to some degree how the paints were made, because at Lascaux pestles and mortars were found in which colors were mixed with no fewer than 158 difierent mineral fragments from which the mixtures were made. Cave water, rich in calcium, was used as the mixers; vegetable and animal oils served as binders.

These caves should not be seen out of context. The area in front of the caves served as a communal site for people to assemble for feasting, gift-giving, and vision-making. Interior spaces were sacred and almost certainly of limited access. Ofierings may have been made and gifts exchanged. These were not caves as we might understand the word today, but ceremonial landscapes located in the “within” of the earth. The appropriate term would be chthonic, a Greek word that means “in or beneath the earth.” In Greek religion chthonic deities were often associated with fertility, and were with rituals that usually took place at night.

In the Lascaux Cave, under the drawing of a rhinoceros, archaeologists found a 21-centimeter-long, spoon-shaped object that they labeled a lamp dating to about 15,000 bce. Meticulously made of polished red sandstone, the upper surface of the handle was decorated with grooves. The lamp is just as beautiful on the back as the front. Because of the perfect symmetrical nature of the cup, the craftsperson must have used some sort of measuring device.

Dozens of such cups have been found, but not all in caves, leading archaeologists to speculate that these were not lamps, but incense burners, used in rituals to produce smoke. When the cup was discovered, it still contained a sooty substance in the bottom, which was determined to be the remains of juniper. Juniper gives off little light, but is highly aromatic. Among the Celts, the smoke was said to aid clairvoyance, and was burned to stimulate contact with the Otherworld during their autumn festival at the beginning of the Celtic year, in central Europe, juniper was burnt as part of a spring-time cleansing of the house. Juniper was used in practically all rituals in Mongolia and by many of the tribes of Siberia, so much so that the air of a hut will often be thick with smoke during a ritual. The smoke is believed to raise the wind-horse that allows the shaman to visit the world of the spirits. For Native Americans, tobacco was smoked not only to produce a calming effect, but more importantly to produce a sacred smoke that speaks to the ancestors. Smoke could also be produced by small amounts of sweetgrass (Hierochloe odorata) burned in the tepee on the ritualistic western side, next to the fire. Sweetgrass was used in peace and healing rituals. All in all, the tradition of sacred smoke was so widespread among First Society people that its origins were certainly ancient. And it still persists today. All we have to do is go to a Hindu temple, which is permeated by incense smoke.

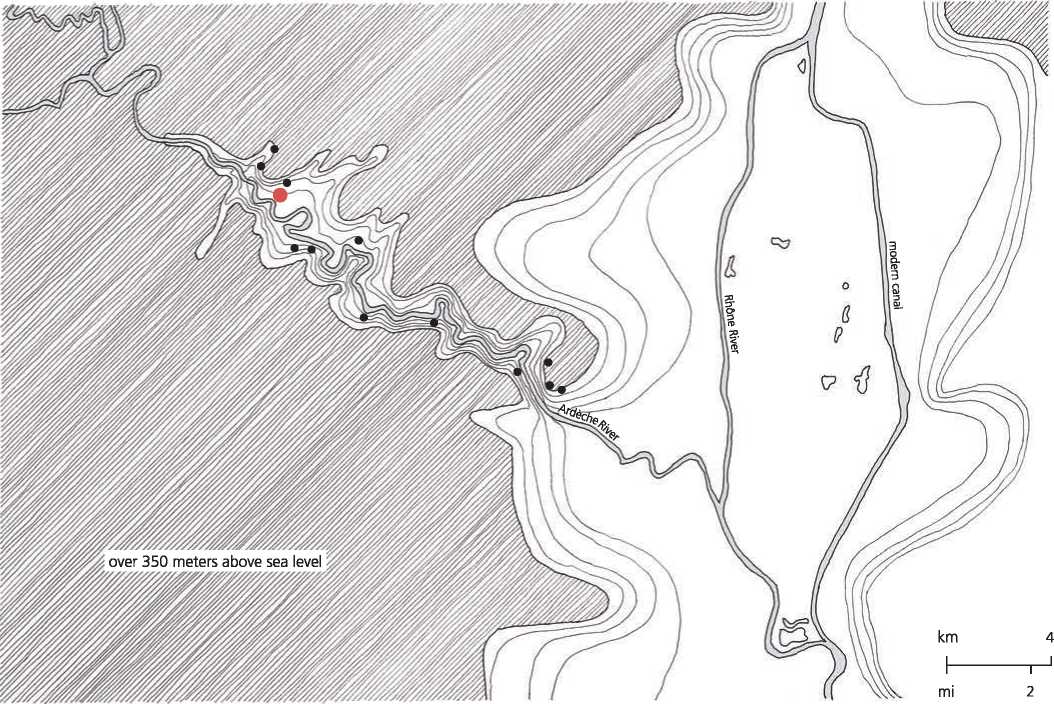

Figure 2.24: Chauvet Cave and the painted caves of the Ardeche River. Source: Sasa Zivkovic/ Jean Clottes, Chauvet Cave: The Art of Earliest Times, translated by Paul G. Bahn (Salt Lake City: The University of Utah Press, 2003), 13

If this applies to these caves, we have to separate the question of how light was produced to paint the images from the question of how these interiors were experienced. Focused as we are on the image of these animals, photographed now with digital clarity, we forget that the drawings, seen flickering in torch-light, would have been ineffective in terms of their magical potency without the smoke and accompanying rituals.

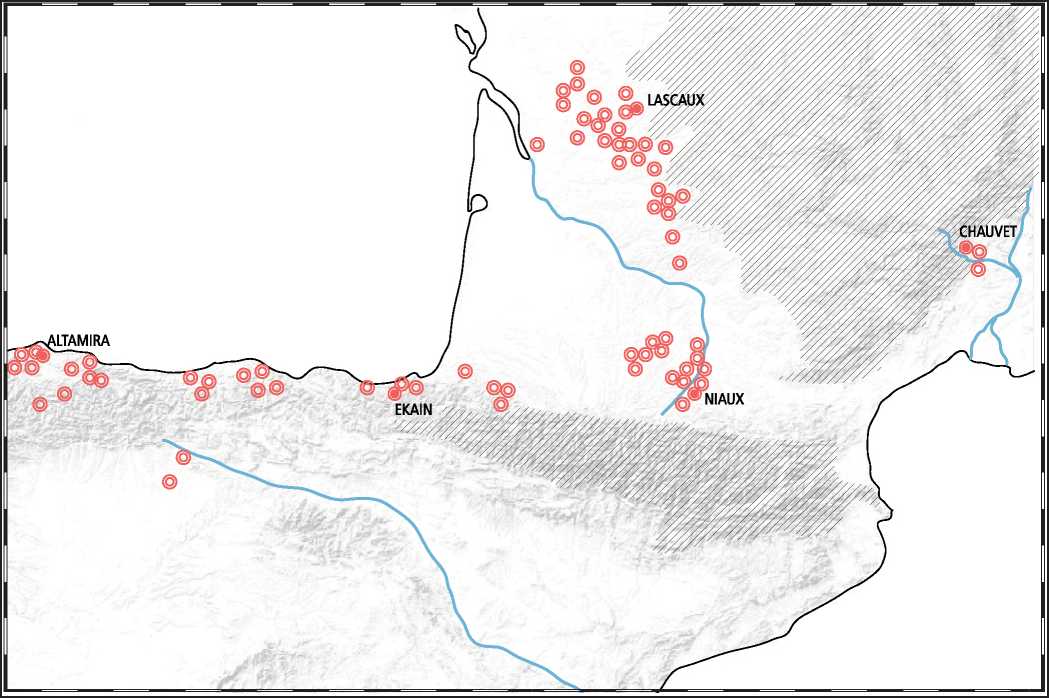

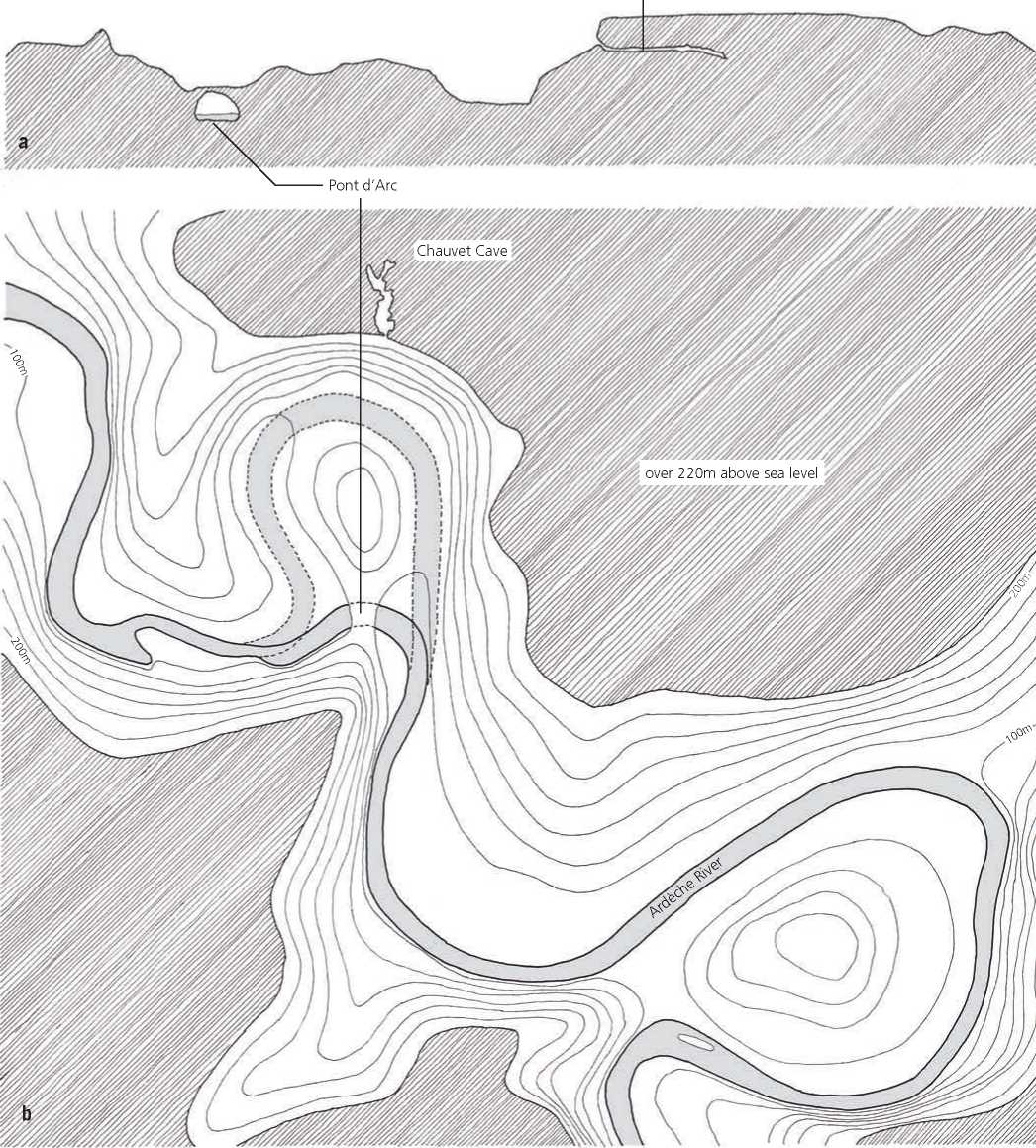

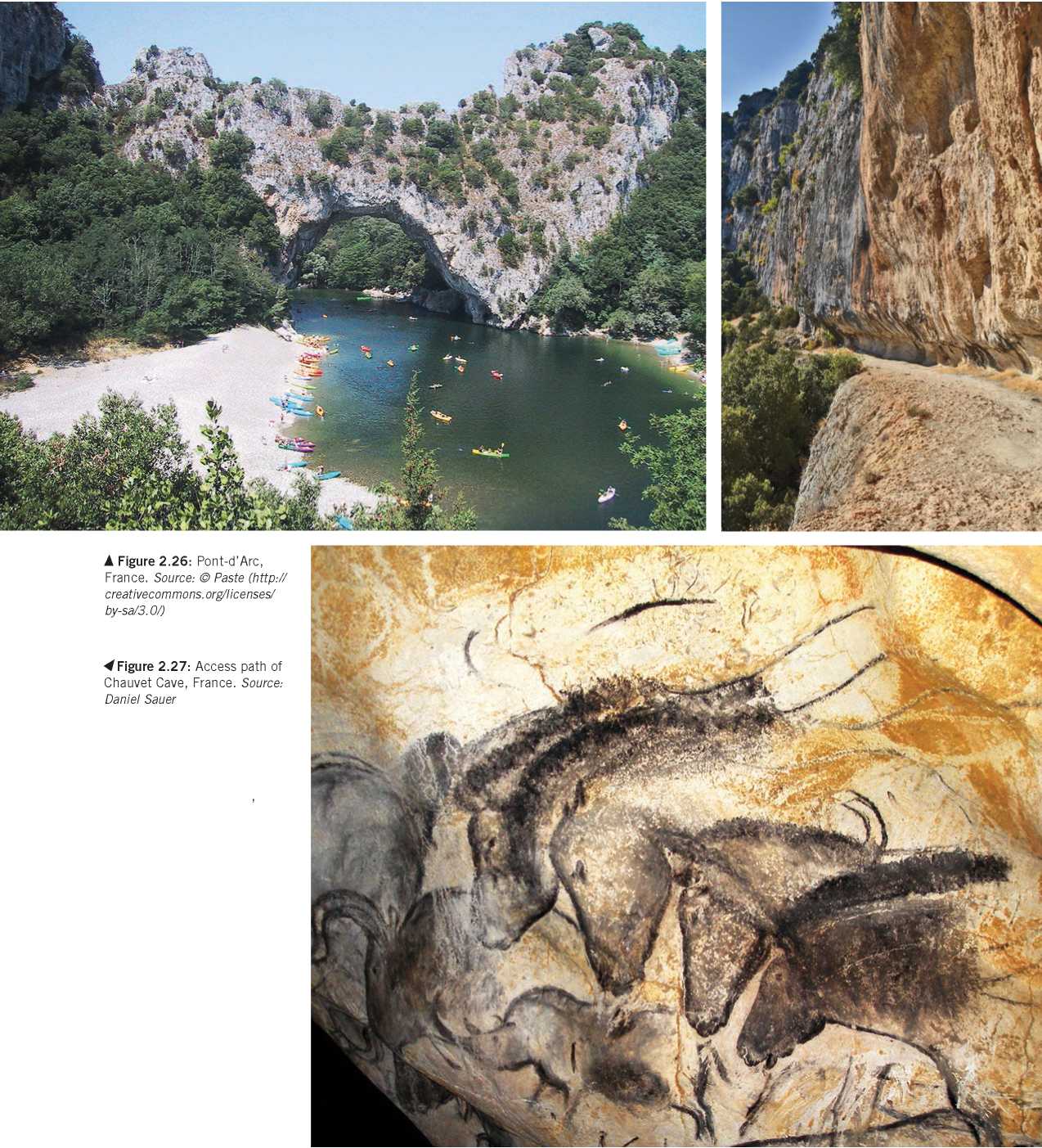

Chauvet Cave, located in a 10-kilometer-long gorge that must itself have been seen as sacred, overlooks a dramatic spot where the river makes a sharp hairpin turn (Figures 2.24 and 2.25a, 2.25b). A natural ledge once led up to the cave entrance, but because of a rock

Slide, the modern entrance is elsewhere (Figures 2.26 and 2.27). There are many chambers to the cave, with hundreds of animal paintings lining the walls, including those which have rarely been depicted in other Ice Age paintings, such as horses, cattle, and reindeer, as well as predatory animals such lions, panthers, bears, and hyenas. Ochre handprints were painted on the walls of the cave, made by spitting pigment over a hand pressed against the wall.

Chauvet Cave

M

Figure 2.25a, b: Chauvet Cave site: (a) section, (b) site plan. Source: Sasa Zivkovic/Jean Clottes, Chauvet Cave: The Art of Earliest Times, translated by Paul G. Bahn (Salt Lake City: The University of Utah Press, 2003), 13

Figure 2.29: Chauvet Cave plan and art. Source: Sasa Ziv-kovic/ Jean Clottes, Chauvet Cave: The Art of Earliest Times, translated by Paul G. Bahn (Salt Lake City: The University of Utah Press, 2003), 117

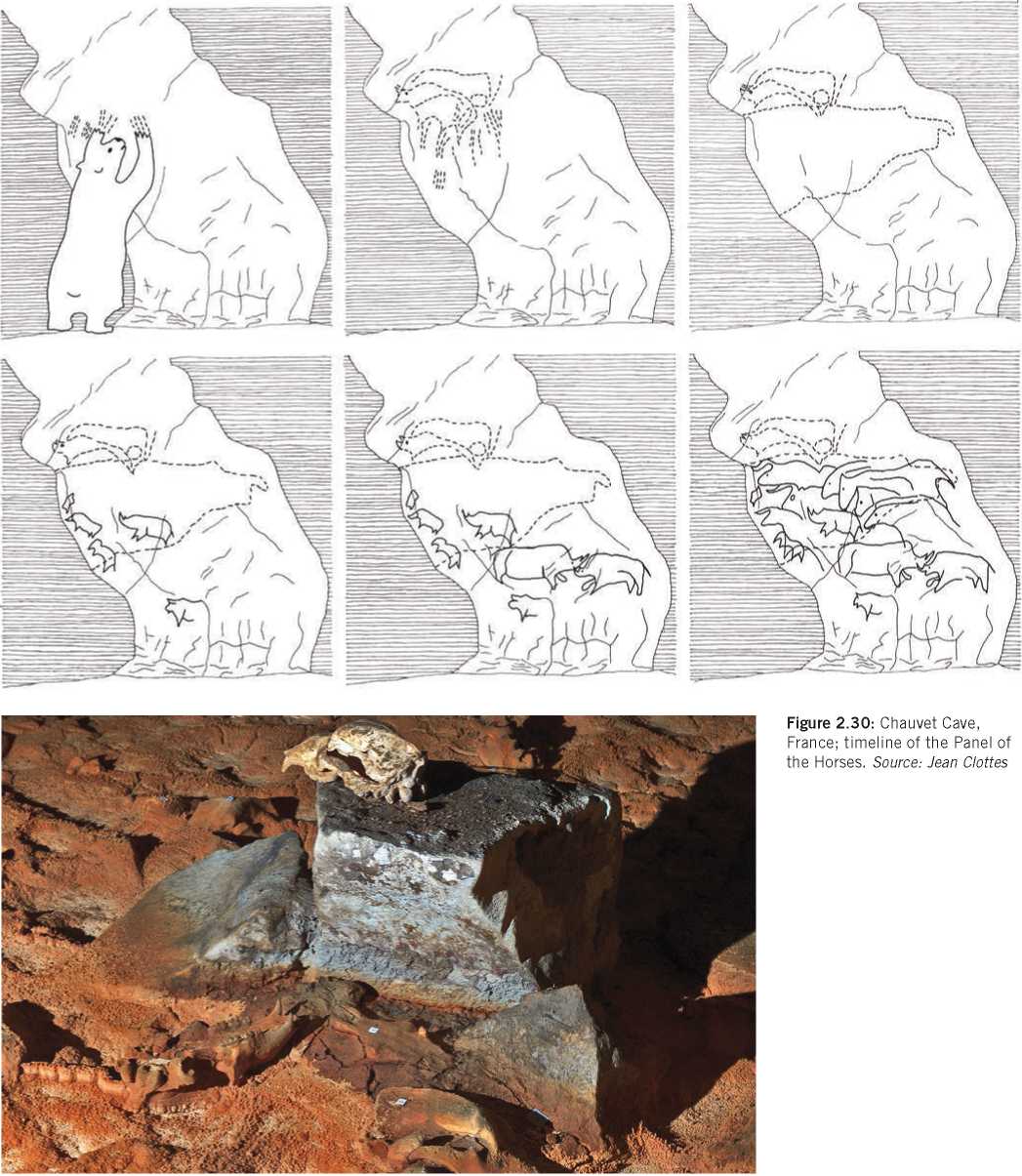

At one place, the artists painted a set of horses (Figure 2.28). Mouths open and breathing heavily, they seem to be running effortlessly behind a herd of bulls and other animals. The whole panel is about 15 meters long and moves its way in and out of the curves of the cave wall. To produce the drawing, the artist first scraped away the surface of the rock to reveal the white stone (Figure 2.30). This allowed for greater contrast with the black charcoal and for a rich pallet of grays. The vigor of the lines and the absence of superfluous details clearly indicate an accomplished artist. Though it was once thought that the artists painted from dead animals, it is clear that this is not the case. How artists perfected their crafi: is not known. The artist who painted these horses must have painted many horses, before he or she attempted these. Did the artists paint on wooden boards in the field? It almost seems so.28

How these paintings functioned is not known, but it is likely that the Chavet was at least partially dedicated to a bear cult. A bear skull has a prominent location in one of the more remote chambers. It was placed on an altar-like stone in the center of a chamber at the rear of the cave (Figure 2.31).

Most of the caves were situated below the elevation of the ice that still covered the Massif Central, a large, mountainous region in southern France, and thus were probably used in the spring afier the first thaw and in context of the bear awakening from hibernation and leaving the cave. Though we can make no direct assumption about the rituals that took place

R rhinoceros B bear BO bovine H hand F feline M mammoth CR crosshatching HA handprint D dots P panther V vulva

Figure 2.31: Chauvet Cave, France. Source: Jean Clottes

Here, animals and the inner mystery of the earth were clearly fused into a potent combination. This is made obvious at the cave El Juyo in the mountains of northern Spain, some 5 kilometers south of the seacoast, where there was a walled-in sanctuary that went through two building phases. It consisted of a hearth and a huge horizontal stone slab resting on smaller upright stones, and nearby a series of pits and mounds. Presiding over it was a face adapted from a stone and modified so that it was half human and half feline. Everything was constructed to

Exacting specifications. The pits, for example, had white coloring matter in the bottom of the trench, with shells of limpets and periwinkles and a shallow layer of clean sand scattered over it. The three clay mounds, about a meter high, were plastered over with clays of difierent colors; red ochre was sprinkled over the area at difierent stages of construction. Near the center of the mound, the tip of an antler, some 15 centimeters long, was stuck vertically, point down, into the ochre. A channel uniting the two mounds indicates that something greasy, probably animal fat, was poured onto one mound to flow to the other one. The main elements of the composition—added in the second phase—was a one-ton, horizontally placed limestone slab supported on smaller stones. The head was placed nearby on the top of an adjacent mound. This was clearly a sanctuary or shrine of major significance.29

This space—even though its use is impossible to determine—is clearly a constructed sacred space. Ofierings were prepared on the hearths and fat was poured on the slabs, all under the gaze of the deity. It is safe to assume that this type of sanctuary-oriented practice was not completely unique; there were probably others. Even so, it represents a significant expansion of architectural practices. Up until now, space was a question of postholes, partitions, protective perimeters, hides, and thatch. Religiosity was transportable or partially ready-made in the form of caves. Here in El Juyo we have a purely symbolic architecture, planned and adjusted over time around a complex set of meanings and associations.

World History

World History