Subsistence

Subsistence strategies of the Chalcolithic relied on a combination of farming and herding/animal husbandry. Two-rowed barley was the most common crop followed by wheat and lentil. Based on studies of archaeobotanical remains, specifically, phytoliths, it appears that simple irrigation techniques were used to assist in the cultivation of wheat and barley. Another breakthrough in farming technology was the use of cattle for traction in plowing, a development reflected in the faunal assemblage.

Of course, animals also served as a primary source of food, with sheep, goats, cattle, and pigs being consumed at most sites (see Animal Domestication), though the latter are rare at sites where there is less rainfall. There was also a growing dependence on products such as wool and dairy, known as the ‘secondary products revolution’, evidenced by the presence of churns and an older population of female animals in the faunal assemblage. The low frequency of pulses at some sites (e. g., Shiqmim) suggests that the people were raising crops for fodder (see Plant Domestication).

Craft Specialization

The success of these subsistence strategies no doubt freed up some time for dabbling in specialized

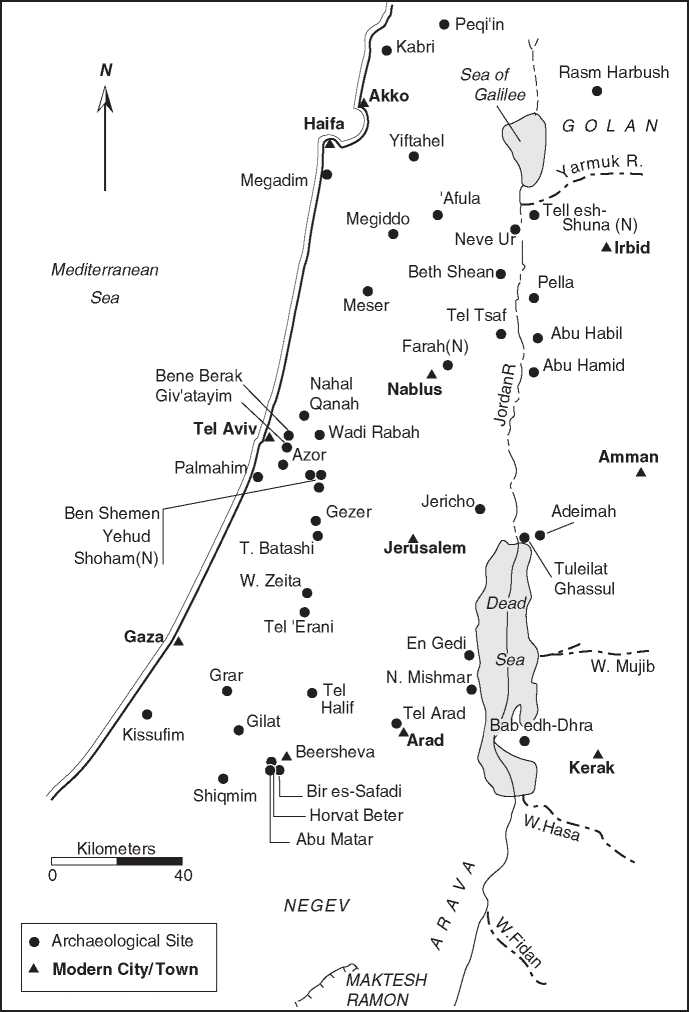

Figure 1 Map of Neolithic and Chalcolithic sites in the southern Levant (courtesy of Y Rowan).

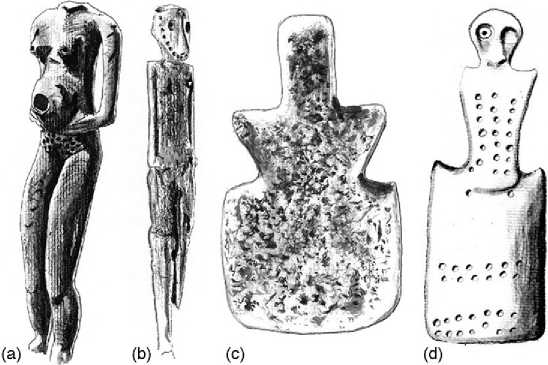

Production activities, and, in time, several craft industries, including ceramic production, textiles, basalt and ivory carving, and metallurgy, would emerge. Chalcolithic ceramic production reached a new level with a wide variety of forms and technological innovations such as the earliest use of the slow wheel. Basalt bowls and the elegant ‘fenestrated’ and high-footed incense stands reflect a high level of craftsmanship in the area of groundstone production. Though little is known about their manufacture, the quality of finished ivory goods, including human figurines and perforated

‘tusks’, also attests to the work of highly skilled craftspeople. Evidence for textile production comes in the form of loom weights and spindle whorls, floral remains such as preserved linseed (flax), tabular scrapers used as sheers, and cloth impressions preserved on the bases of ceramic vessels; in rare cases such as the Cave of the Treasure (Nahal Mishmar) and the Cave of the Warrior, the textiles have been preserved.

The most outstanding technological development of the Chalcolithic was the local inception of copper. Though the initial technology may have been

Figure 2 Chalcolithic figurines: (a) ivory female from Bir es-Safadi (by J. Golden, adapted from Perrot 1968: Pl. 5); (b) male ivory from Bires-Safadi (by J. Golden, adapted from Perrot 1959: Pl. II); (c) stone ‘violin-shaped’ figurine from Gilat (by J. Golden, adapted from Alon and Levy 1989); (d) bone anthropomorphic figurine with violin shaped elements (by J. Golden, adapted from Levy and Golden 1996) (not drawn to scale).

Introduced from elsewhere, by midway through the period, local smiths were producing metal at an advanced level. Two distinct industries have been identified: one based on the open-casting and hammering of relatively ‘pure’ copper to manufacture tool-shaped goods; and another involving the casting (lost-wax) of complex metals (i. e., copper with arsenic and antimony) to manufacture a range of goods, some quite elaborate in design (see Figure 3). Evidence for the ‘pure’ copper industry is known from village workshops such as that of Abu Matar and Shiqmim, while evidence for the complex metals industry is extremely rare. There are now, however, some indications that the two industries may have overlapped more than previously thought, and new clues pointing to the local production of complex metals have begun to surface (see Metals: Primary Production Studies of).

A staple surplus would have been required to support the activities of craft specialists that were engaged in nonfood production, and evidence for communal storage facilities has been found at large central sites such as Gilat and Ghassul, suggesting a surplus of agricultural products, probably wheat or barley. The people of the Chalcolithic also engaged in longdistance trade, as material used to manufacture many of the fancy metal goods probably came from distant sources. Obsidian found at Gilat can be traced to sources in Turkey, and it is possible that some goods, such as ivory or the gold from Nahal Qanah, came from Egypt.

World History

World History