The push northward into Germany, Poland, and into Scandinavia produced a distinctive architectural form, the longhouse.4 The culture to make the move into Europe is known as the Linear Pottery culture (5500-4500 bce), followed by the Rossen culture (4600-4300 bce). Their settlements spread along the major river valleys. Initially, the Danube and its tributaries were the main corridors, with the farmers discovering that the upland zones were covered by loess soil, a fine wind-deposited sediment that is exceptionally fertile. Within the loess zone, farming settlement spread to the headwaters of the river systems that drain north to the Baltic and North seas: the Elbe, Rhine, Oder, and Vistula.

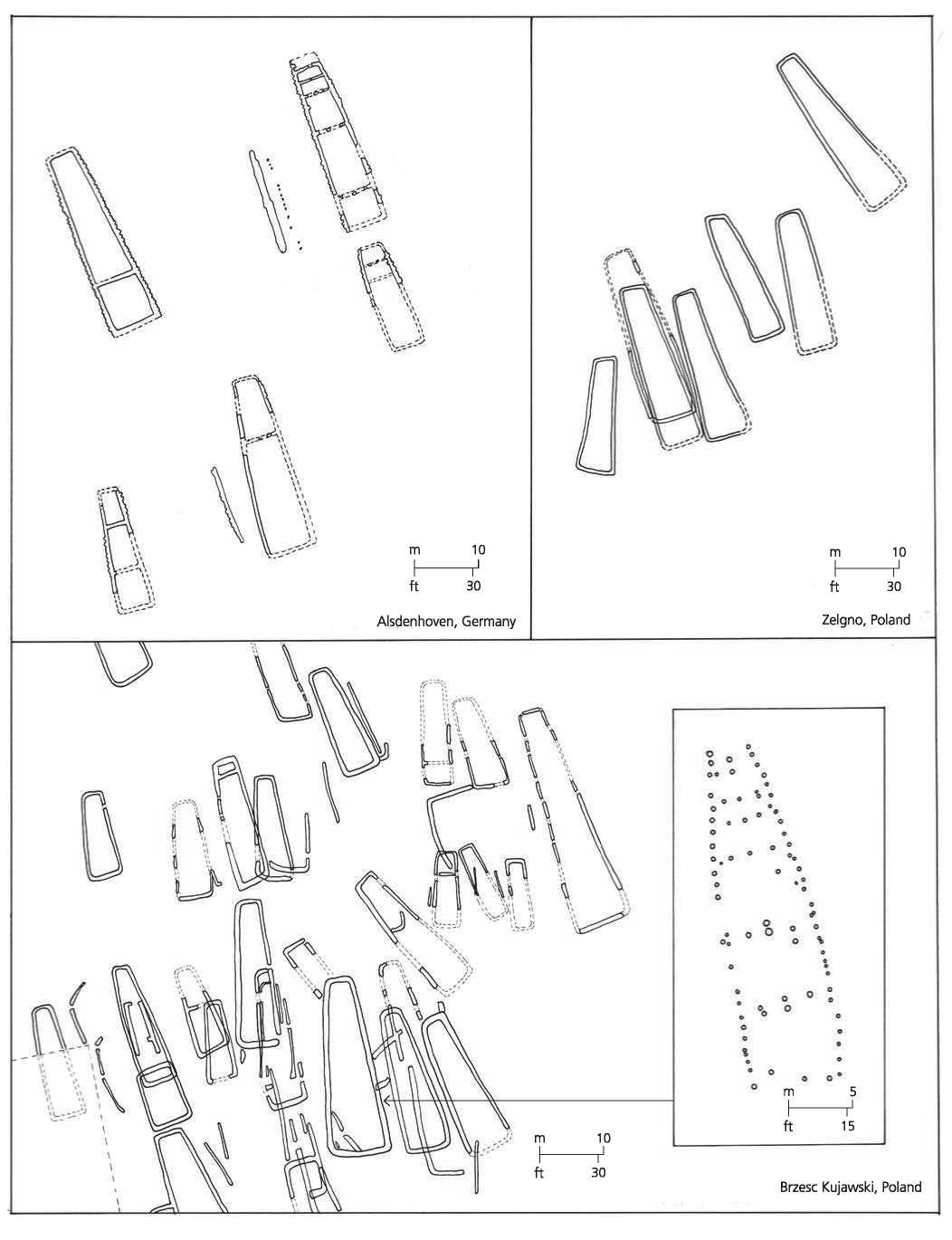

The round hut, pit house, or various other constructions that had been made for millennia fell to the wayside. Instead, the more or less rectangular house, though sometimes with a rounded end, became the norm. The first longhouses of the Rossen culture had a unique trapezoidal shape, with the entrance at the wider end. A site in Oslonki, Poland (4300 bce) was actually a fortified settlement with nearly thirty trapezoidal longhouses and over eighty graves (Figure 10.2). The graves of the more affluent had included copper items (some of the earliest in north-central Europe, with sources several hundred kilometers distant), shell belts and necklaces, bone armlets, antler axes, and bone points. Antler axes occur with male burials, while females have belts of shell beads; copper occurs with burials of both sexes. Though ofi:en described as agriculturalists, they were actually agro-pastoralists, since they had cattle, pigs, sheep, and goats.5

Though there are several regional variations to these longhouses, most have three or four internal divisions. Massive internal posts in the center held the ridge beam. Some have a double row of postholes along the walls, suggesting that the post held a horizontal beam between them that in turn supported the rather significant weight of the roof and its beams. Lengths of these houses range from between 10 and 60 meters, although most are about 20.6 The part closest to the door was for work activities, the middle section for sleeping and eating, and the rear for grain storage and ritual activities. The houses had an attic that was used for storage and sleeping. Twenty to thirty people would have lived in these structures. Such a house would also have had outdoor work areas associated with it as well as animal pens, and, on the nearby slopes, its agricultural plots. Unlike the Mesopotamian houses, which were associated with neighborhoods and usually quite compact, these structures were political units in and of themselves, even though they were always tied in to other neighboring houses. A village would have consisted of five to twenty-five longhouses, with houses being rebuilt over the centuries close to where the old one was.

A longhouse in Albersdorf, Germany gives us a vivid picture of domestic life. It was 13 meters long and 4.8 meters wide and was divided into various rooms by lightweight partitions. At the narrow northwest end, the posts were more closely placed next to each other. This “weather side,” which was more exposed to wind and rain, was thus better protected. The walls were filled in and sealed with clay. The inner and outer surfaces of the walls were then smoothed and covered with chalk as a sealant. A grave was found in the northernmost room, and nearby in the northeast corner were marks from a big boulder that once stood there. This room served ceremonial purposes having to do with ancestor veneration. This house was more than just a functional unit. It operated as part clan compound and part ritual center serving the immediate community.

The idea was not to create a concentration of people bound by architectural form into a relatively static grouping, as at Qatal Hoyuk, but an architecture of modularity, namely of house units that could be multiplied within the limits of social and economic tolerances. A “house” was more than just the building and its inhabitants. It was an economic and ancestral entity, with the core members of that entity living and working in the actual house and others living nearby in more informal or smaller structures.

Figure 10.2: Rossen and Lengyel longhouse foundations. Source: Mark Jarzombek/Http://antiquity. ac. uk/projgall/czerinak297

Unlike the huts of an earlier era, which were mostly made by women, the making of these farmstead houses was a community effort. Men chopped down the trees and prepared and carved the wood, women made the daub, which was applied by the women, the elderly, and the children. Families probably helped each other during the construction, similar to a “barn raising” where neighbors work together in the context of food, drink, and merriment. Construction was done either in a single concentrated episode or by small groups incrementally. First trees needed for the construction had to be identified, maybe years in advance: oak for the structural parts, and pine, which could be split, for the wall and floor boards. The more incremental tasks could then begin. These included the weaving of the walls out of saplings and sticks, the procuring and carrying of the heavy clay to the site, its mixing with dung and plaster to form daub, and then the plastering itself. The thatching, which was probably done by the men, had to be conducted relatively rapidly, with most of the thatch bundles prepared ahead of time by the women. Roofs overhung the walls as far as possible to protect the walls from rain. The communality of the effort as well as its relative flexibility of the construction process underlay the autonomy of the nuclear household as the elemental unit of society. It also meant that the house could be identified with the entire range of generations and with both sexes. The effort was substantial, but was not seen as “work.” Rather it was an integral part of a family in identifying its place in the social and physical landscape.

Most activities still took place outside the house. This was, after all, a working farm with people spending their daylight hours doing chores in and around the village. Making pots was a particularly important activity because pots were required for both functional and ritual activities. It was a valued skill that was carefully learned and handed down through the generations. Much effort was made with decorating surfaces, particularly for serving vessels. Grinding ochre, as always, remained important for burial rituals and body ornament.

This emphasis on separate households, on the one hand, and on a number of households working in unison, on the other hand, was unique at that moment in history. Though villages needed a certain number of people to be fully operative, it also had an upper limit of maybe about two hundred people to balance resources and activities. When the limit was reached, groups would branch off and found a settlement elsewhere. These villages were organized, however, with limited hierarchy. Tradition and ancestry spelled out the logic of behavior. One or the other family held sway over the group, and some families would have had access to the better land and resources, but mostly the organization depended upon participation rather than on status.

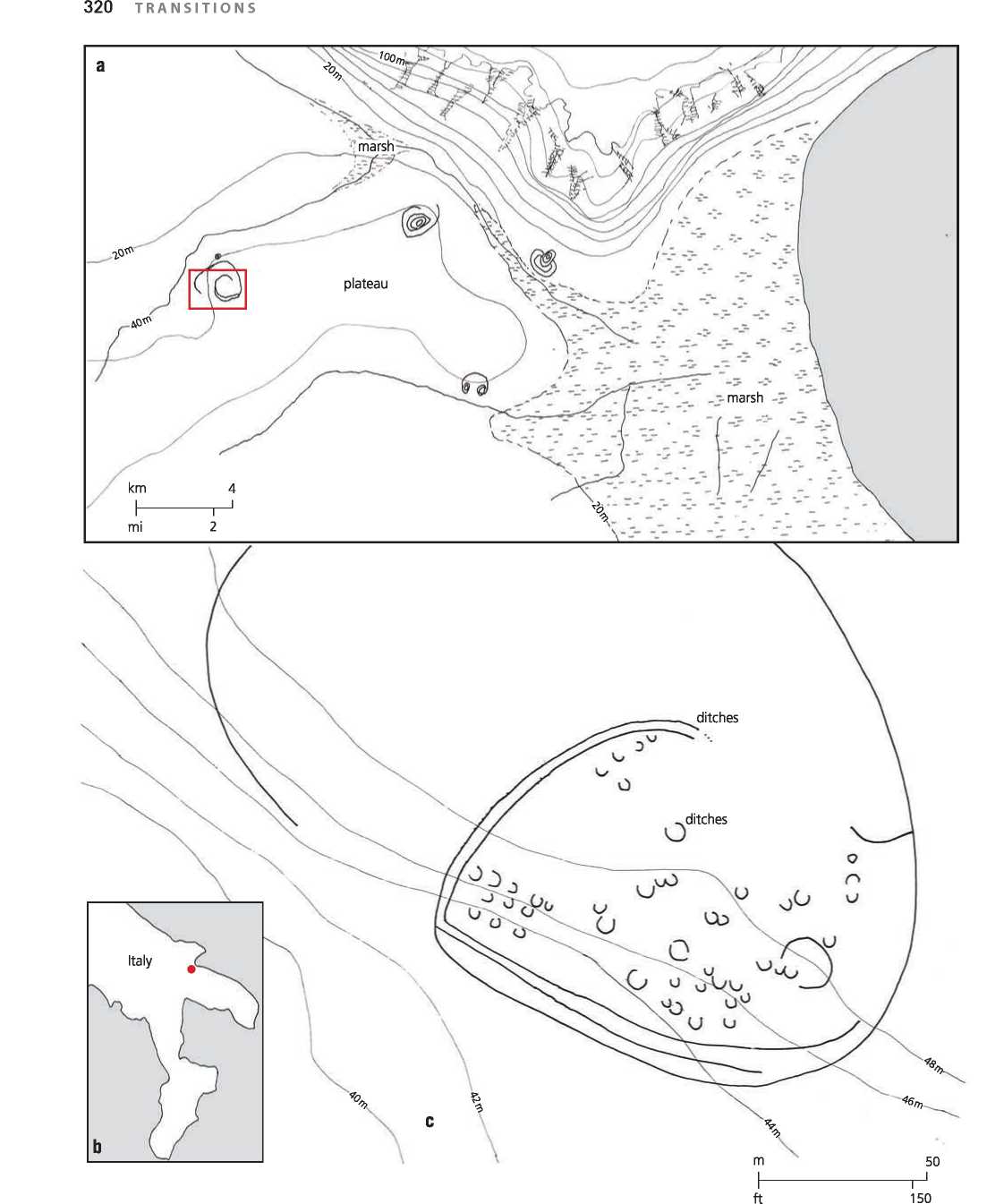

Many of the early villages were bounded by ditches, usually 2 or 3 meters wide and the same amount deep, but these might not have been as much defensive as symbolic, and perhaps even practical, controlling the movement of cattle. The ditches defined an area usually about 200 meters across, becoming somewhat larger over time. In some cases, as at Passo di Corvo in Italy (ca. 5500 bce), the C-shaped ditches had a drainage function that channeled the groundwater away from the house (Figure 10.3). The ditches left circular areas of about 20 meters across, which served as a platform for the house and its surrounding work and animal space. Large, spiraling canals encircled the settlement. It and its neighboring settlements were located on a plateau, which begins to drop off on its eastern and northern sides marshes. If the plateau served as a grazing area, the marshes provided for fish, fowl, and other game and plant food. The long ditches, which loop around the settlements, apart from ritual functions, served as water retention during the summer months.7

As to the size of the village, that can be determined by the number of animals. Below certain herd sizes, the herd is vulnerable to disease, climate, and predation. The minimum size of a herd is about thirty, fifty preferably. A village would have had to have at least that number. To this one adds sheep and pigs to arrive at a figure of about how big

Figure 10.3a, b, c: Passo di Corvo, Italy. (a) site plan, (b) map, (c) one of the settlements. Source: Mark Jarzombek/Santo Tine, Passo di Corvo e la civilta neolitica del Tavoliere (Genova: Sagep, 1983)

A village would have to be to be sustainable over time. Most villages consisted of around ten families, but many were larger. Passo di Corvo had ninety compounds, but they were probably not all in use at the same time. The area outside the village was defined by a range of economic realities. Pastures for the cattle were needed as well as garden areas and fields, protected from the animals by stone walls and fences. Some areas had to be left fallow. Other areas were needed for lumber and firewood. For all of this, it seems that 3 to 5 kilometers was the right amount of distance between villages. There were also hunting areas in the hills and on mountain slopes, and though fishing was not a major preoccupation, rights to the banks of rivers were certainly negotiated with the neighbors. Whether everything was peaceful is not known, but probably not. During times of stress there might have been raiding parties to steal cattle. Villages in the more populated low lands were certainly more prone to conflict.

On occasion, members of several villages banded together to go on the road, so to speak, to visit the regional mines for flint and ochre or to go to places to trade for obsidian, metal, or other commodities. These paths would have been well-known, requiring certain protocols on how to move through foreign territory. Sea travel, though perilous on the early log canoes, did not intimidate them. After all, Crete, Cyprus, and Malta and any number of other islands were settled already between the sixth and fifth millennium BCE. Boating was probably undertaken by specialized boat crews who brought obsidian and trade commodities to various ports of call during the summer months when calmer weather was common.

Apart from what people grew in their fields, there were cherries, apples, mushrooms, pears, and other forest products that when dried would last into the winter. Honey and berries were also collected, as well as herbs of various types. Salt, if not found locally, was procured through trade. Animals were not technically considered food, but there were always enough ritual excuses to merit a sacrifice.

A visitor moving into a village would have seen areas of new gardens, half-regenerating gardens, worn dirt pathways moving in different directions, a number of clearings, a soft haze from the smoking fires, and the thatched roofs of the houses through the thinning trees. The visitor would have already attracted the attention of the dogs and inquisitive children, with the adults watching warily from their tasks. Then, stepping into a wide opening, she would see the village itself surrounded by a ditch and wooden palisade, with the noise of the people, children, dogs, and animals, now all around.

Much as with First Societies, the surrounding landscape was still seen as sacred. Peaks and rocks were honored and caves were still held in reverence. Many aspects of the sacred landscape might have, in fact, been borrowed from the First Society people, some of whom might still have been found in the highlands. In a cave in Italy that was preserved because of a rockslide, bowls had been placed on the floor to collect the water dripping from the roof. The water was probably considered sacred and used in healing ceremonies. Not too far away at another cave, in a set of low, tortuous galleries, hundreds of images were painted, some geometric, others showing men hunting deer. In ways that would also have been familiar to First Society people, there people still worshiped figurines, mostly of women. In fact, the figurine world was to remain a part of culture from the middle European areas around to Egypt for a long time to come. At Passo di Corvo, archaeologists found a statuette of a female figure with halfopen eyes, in what seems an altered conscience condition. She wears a necklace and has markings on her upper torso. The traces of red pigment indicate that she had been painted.8

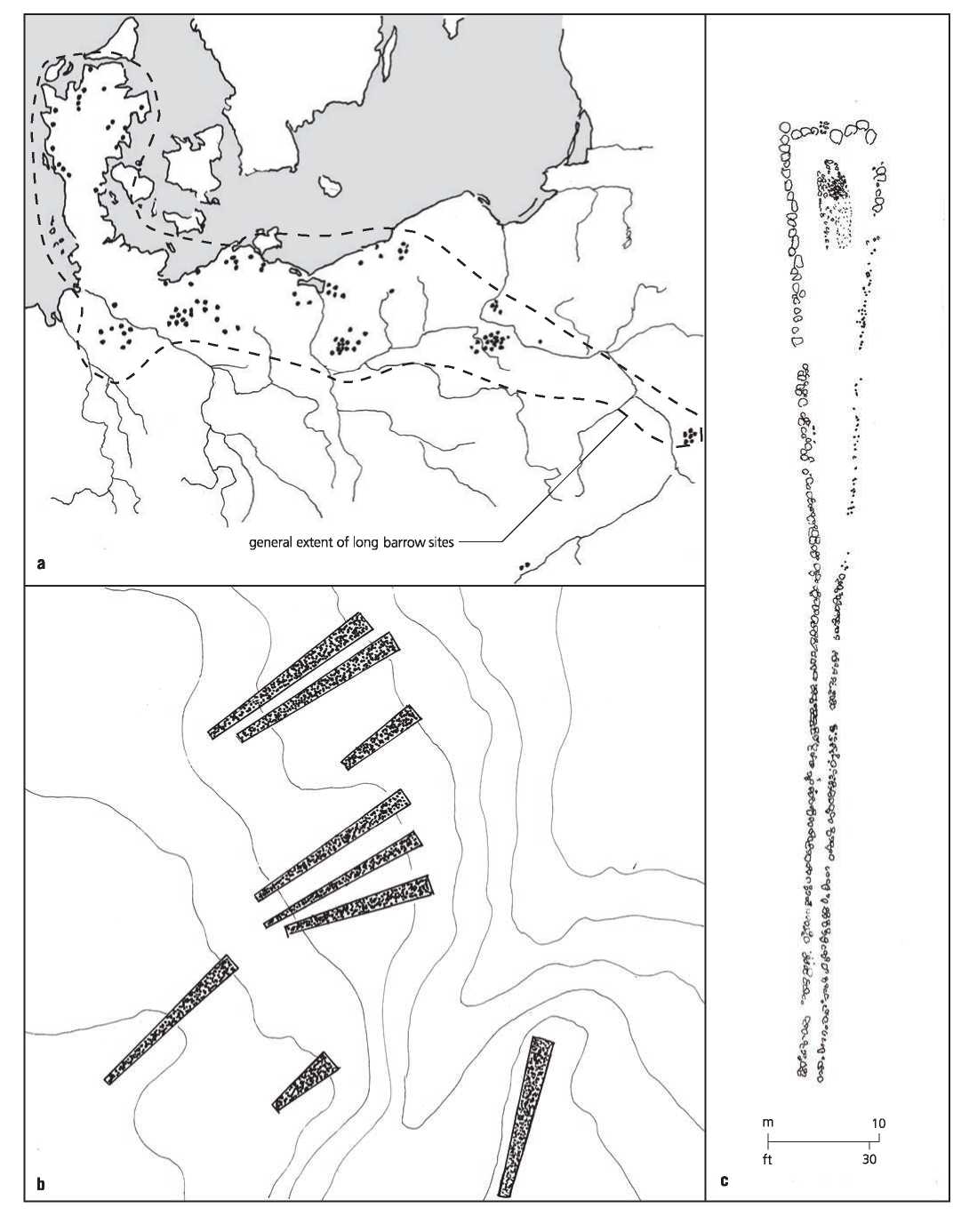

Figure 10.4a, b, c: Long barrows in northern Europe; (a) general extent of barrow sites in Europe, (b) site plan of Sarnowo, Poland, (c) remains of a typical barrow. Source: Mark Jarzombek/Magdalena Midgley, The Origin and Function of the Earthen Long Barrows of Northern Europe (Oxford: British Archaeological Reports, 1985), 25

Figure 10.5: Wietrzychowice Long barrows, Wietrzychowice, Poland. Source: Cezary Namirski

World History

World History