To the east of the Mississippi, the end of the Cahokian era and the evacuation of the American Bottom had a particularly negative impact on the region. It produced a period of village violence the likes of which the Americas had never before seen. In earlier times, warfare had been tied to prestige and aristocratic posturing among the clans. Conflict was rarely sustained. But when the American Bottom was abandoned, tens of thousands of people were displaced. Some tribes migrated west to the open prairie, others headed south into present-day Mississippi. Those who happened to control sacred territory and resources had to protect themselves from intruders. Life, of course, did go on, but in many places, at a reduced cultural level.

29 25 52 N, 81 38 56 W

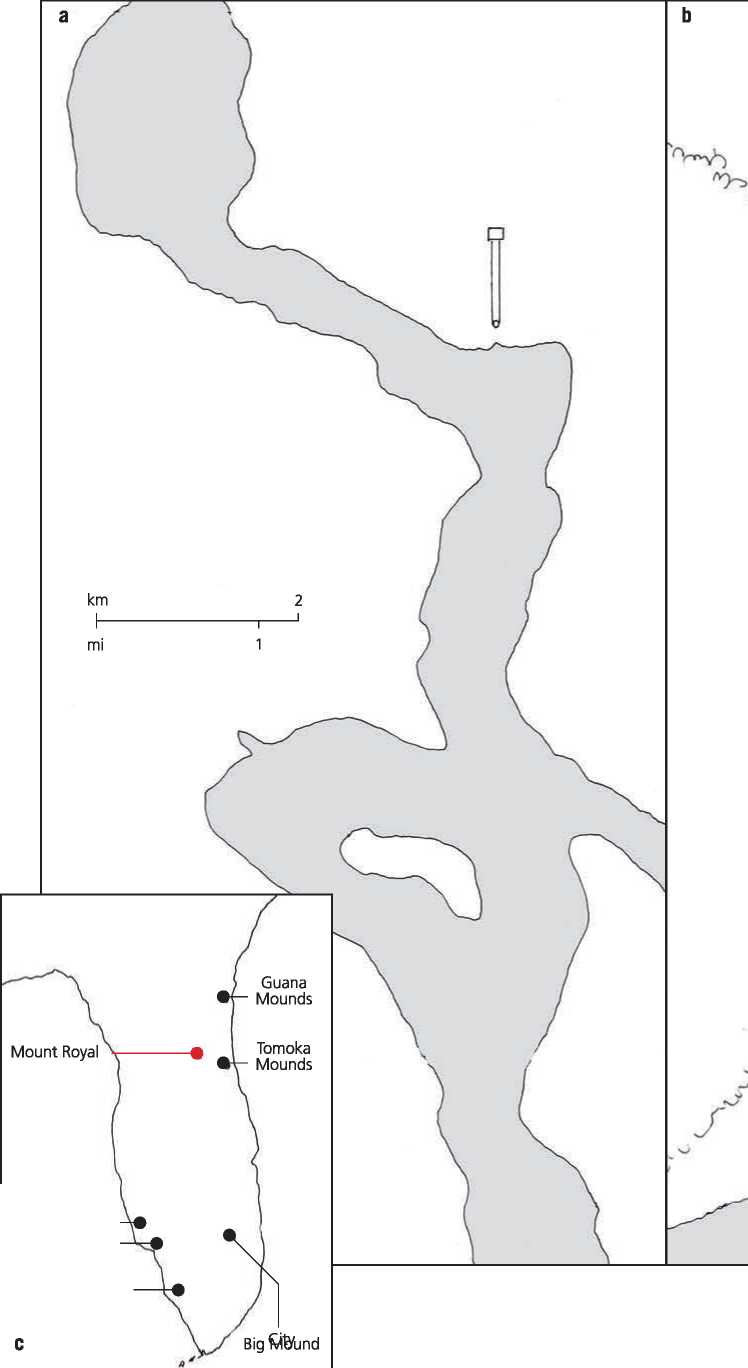

The only place where Cahokian-styled life found a legacy, although at a smaller scale, was not along the Mississippi itself, which was unsuited for corn growing due to its volatile flooding, but on the shores of numerous other rivers in the states of Mississippi and Georgia. Dozens, if not hundreds, of settlements were founded, all with a ceremonial core. Most of the mounds were in red clay, but some were yellow and few even in blue. Most ceremonial places had several mounds that, of course, were expanded over time. The villages lined the nearby waterways and streams. One place of particular importance was Mount Royal, on the eastern bank of the St. Johns River, about 40 miles south of St. Augustine. The site, probably the burial place of chiefs and a high-status leadership group, was built up between 1100-1600 ce, with the main mound made up of alternating layers of yellow and white sand with a top deposit consisting of a mixture of red ochre and sand. One side of the mound had a 750-meter-long ceremonial avenue that extended to a lake. Some archaeologists think that the builders of the Mount Royal mound actually created the lake by using its dirt for the structures of that area.27 Along the length of the ceremonial avenue, several artifacts were found, such as gem stones, copper beads, and a copper breast plate that can clearly be linked to the Mississippi culture (Figures 16.43 and 16.44a, 16.44b).

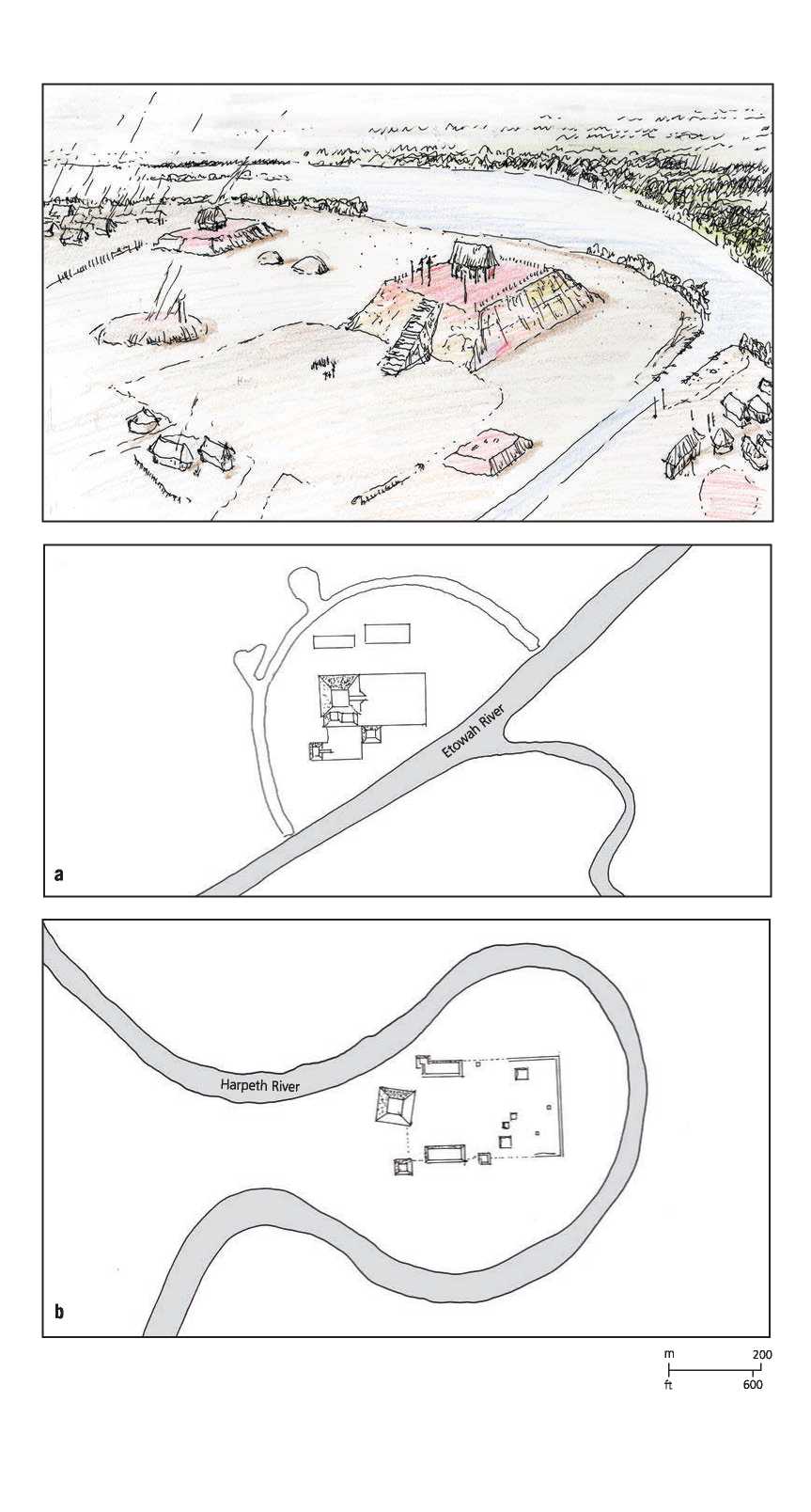

Figure 16.44a, b: Two ceremonial sites: (a) Etowah, Georgia, USA, (b) Mound Bottom, Tennessee, USA. Source: Mark Jarzombek/ William N. Morgan, Precolumbian Architecture in the Eastern North America (Gainesville: University of Florida Press, 1999), 197, 189

Figure 16.43: Typical southest ceremonial area. Source: Mark Jarzombek

Mount Royal belonged to the Timacua, who inhabited the northern part of the peninsula. They were described by the Spanish, who encountered them, as having a society divided between the nobility and the common people, where the subchiefs and those lower in rank will pay tribute to those further up in the form of food, goods, and labor from their subjects. Although the chief’s decisions were absolute, he always made them after holding a general council at his dwelling. Although not warlike, heroism was valued. Their villages were circular in form and surrounded by a palisade of tree trunks twice the height of a man, set firmly in the ground with an interfolding entrance. The dwellings were also circular in plan, built with one opening, the doorway, and a conical, palmetto-leaf thatched roof. A variant form of architecture was the chief’s abode, which occupied the center of the village and was often used as a meeting place. It was rectangular, not circular, and larger than the houses of his subjects (Figure 16.45a, 16.45b, 16.45c).

Occasionally there was a large dwelling measuring from 20 to 30 meters in diameter, which housed an entire village of over one hundred people. Arranged around the inside wall were the individual compartments for each family. The entrance to each faced the central area, which was sometimes only partially roofed. Two types of beds were used; one type was hewn from a log to fit the general contour of the body, the other was an open wood or reed framework elevated from the ground. Moss was used to pad the beds. The beds lined the walls of the abodes and were used as lounging or sitting places during the day. At night, they lit small fires under their beds to drive away insects. The descriptions remind one of the shobono of the Yanomami in Venezuela and Brazil.

Pottery was made by molding clay in a rush basket that was then burned away, leaving basket marks on the surface. It was of high quality and could be used for boiling water. Canoes were fashioned from a single log. Chiefs wore a long cloak of painted deer skin. Noblemen wore copper plates around the neck. In early March a sacrifice was made to the sun. A large stag was killed and the skin with head attached was stufi'ed with fruit and grain and decorated with garlands of flowers and the whole placed on top of a pole facing the sun. The shaman, with the chief next to him, ofiered prayers, while the common people danced and sang sacred songs.

Upon death, the body was cut into pieces, the skin was removed, and the bones were stored in ossuaries before final interment. The pottery that was placed with the bones had been ritually broken. The mounds at the burial site were seen as a city of the dead, replicating the relation of clans in an actual village. When a chief died, his body was placed in a mound of his own, surrounded by arrows fixed into the ground and at the summit was placed his drinking shell. This was followed by three days of fasting. The chief’s personal possessions were placed in his dwelling and the whole burned.28

26 52 29 N, 80 28 39 W

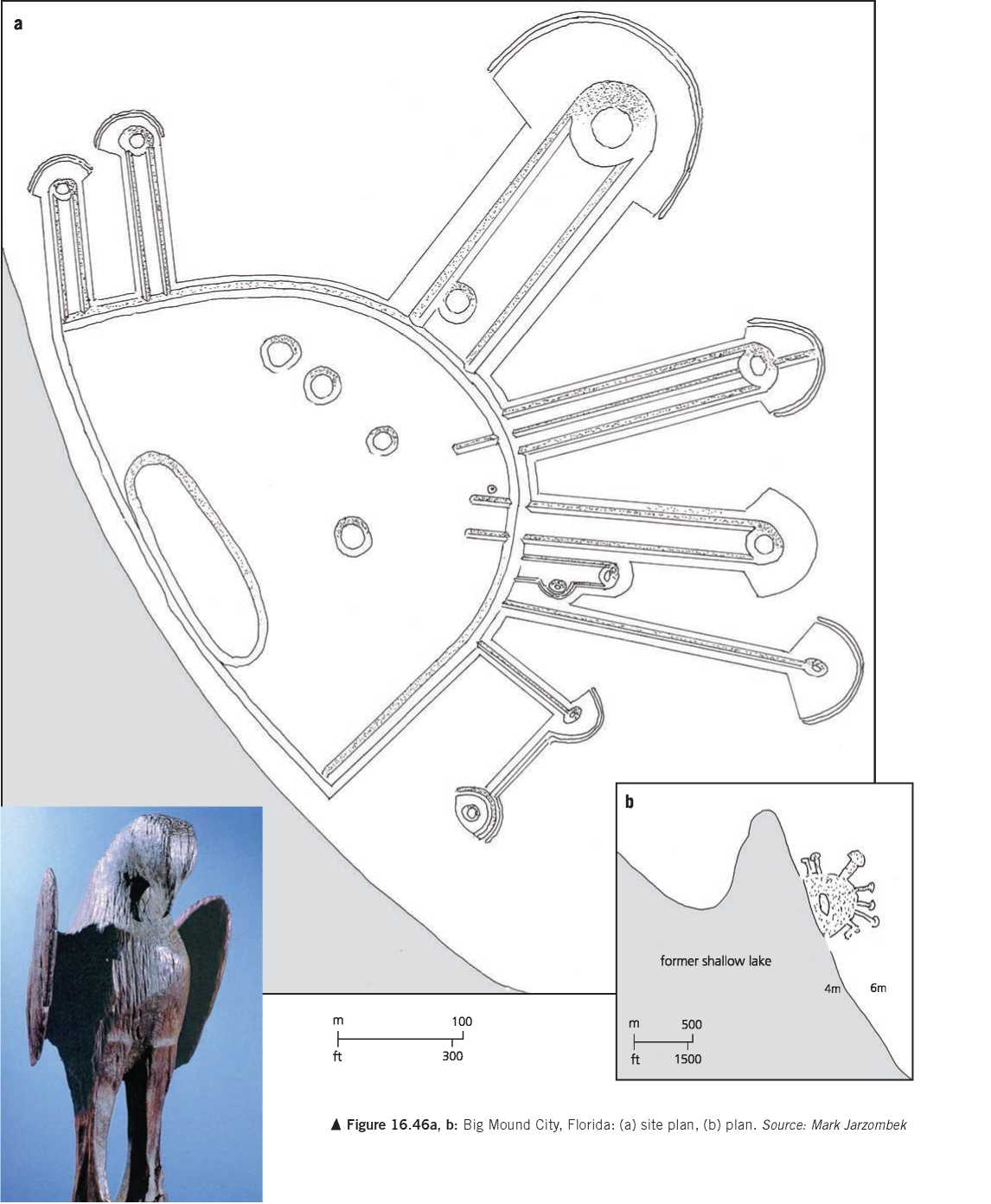

Another Florida site is known as Big Mound City, to the east of Lake Okeechobee. Sited on a low berm next to the former shore, it has an astonishing design. The central plaza was huge, 463 meters across and in the shape of a D. It contained several mounds. Branching off from the plaza are several ceremonial avenues terminating in other mounds, one of which is a formidable 33 meters in diameter and 8 meters high. Most were made from yellow sand. The entire area of the “D” was surrounded by a sacred waterway. There can almost be no doubt that this represents a conceptual map of the communal tribes who gathered there. The village platform, a long oval, dominates the southwest edge of the great plaza. Only two of the mounds were burial mounds (Figures 16.46a, 16.46b, and 16.47). The site, originally partially flooded during the wet season, was used by the Calusa as a ceremonial meeting ground and was in use until the time of the Spanish conquest. Very little in the way of the wooden architecture built on these mounds has survived, but a few remnants of the sculptural agenda have been found, including a 2.5-meter-high bird. Such figures, along with decorated poles, would have been a common sight on these mounds.29

Pine Island — Mound Key

Morris Island Mound

Figure 16.45a, b, c: Mount Royal, Florida, USA. Source: Mark Jarzombek/William N. Morgan, Precolumbian Architecture in Eastern North America (Gainsville: University of Florida, 1999), 213, 221

Artificial

Pool

|

R | ||

|

C | ||

|

C | ||

|

K |

V | |

|

N |

E | |

|

C | ||

|

) |

C | |

|

/ | ||

|

> |

C R- | |

|

C | ||

|

'i |

J | |

|

> 's |

<L | |

|

J | ||

|

[ | ||

|

C C ( | ||

|

¦» 1 | ||

|

R> |

C I | |

|

Bj |

R | |

|

"A |

Mound

< Figure 16.47: Eagle, Fort Center Mound, Glades County, Florida. Source: Courtesy Florida Museum of Natural History, catalog no. 62355, photo by Roy Craven

World History

World History