Experimental archaeology is as old as archaeology itself. The first archaeological experiments probably date back to the sixteenth century, when Renaissance scientists like Agricola and Mercati laid the foundations of elementary scientific archaeology.

The oldest described experiment we know of originates in Germany when clergyman and archaeologist A. A. Rhode produced a flint axe by himself to support the theory that these objects were man-made. From then onward, both scientists and laymen contributed to the development of a corpus of experiments which archaeologists could use to falsify or verify their hypotheses. Falsification is feasible; nowadays, the opinion is such that verifying hypotheses is impossible, hence only validating them is undertaken.

‘Old’ experiments across Europe and beyond in the seventeenth to nineteenth centuries are documented. These were called experiments in the sense of ‘‘any honest effort to understand ancient artifacts by actually working with them’’ (Coles, 1979, 11-12).

In these early days, questions were raised about the provenance (nature or human) of objects, whereas later experiments were more into how things exactly could have been made and how they could have been used. Were they in any way useful to modern standards?

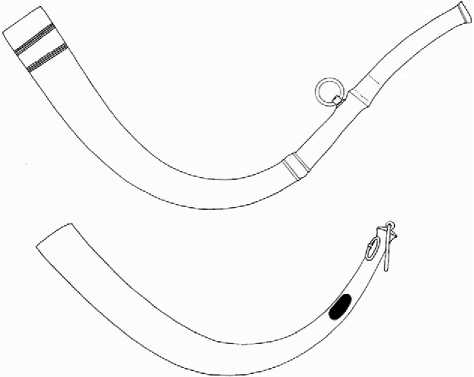

Some years before 1860, for example, a number of horns were found in Ireland. These were not normal end-blown instruments, but were blown from the side (Figure 1). They could be tested in order to see what sounds could be extracted from them. This was a nondestructive method in which the artifact itself remained complete. Partly depending on the skills of the users, different musical notes could be derived. The report describing attempts to blow these horns sadly describes: ‘‘And it is a melancholy fact, that the loss of this gentleman’s life (Dr Robert Ball, rp) was occasioned by a subsequent experiment of this kind. In the act of attempting to produce a distinct sound on a large trumpet... he burst a blood vessel, and died a few days later’’ (quoted in Coles, 1979, 14).

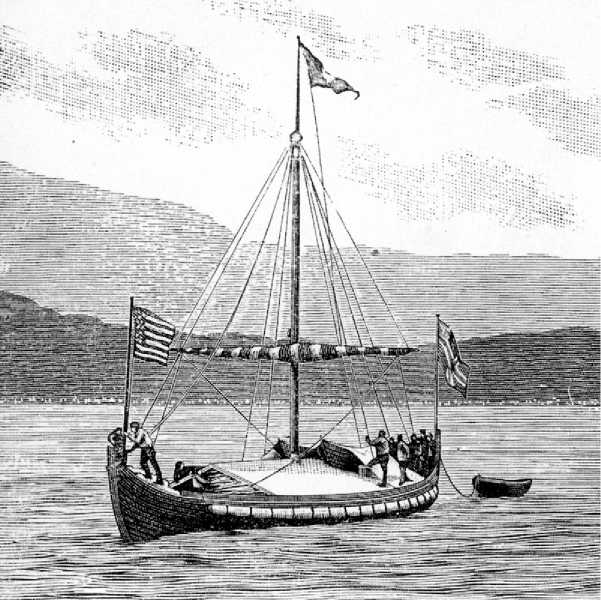

In 1893, at the World’s Columbian Exposition in Chicago, the last of the large World’s Fairs of the nineteenth century took place. It was themed around the 400 years commemoration of Columbus’ travel to America. Some Norwegians - nonarchaeologists - thought it to be a good idea to send over a Viking ship replica, just to make clear, there were other Europeans who had gone before Columbus. This would draw

Figure 1 Bronze horns from Drumbest (Co. Antrim, Ireland), c. 700 BC (Ulster Museum, Belfast). Drawings from Coles, 1963, quoted in Coles 1979, p. 14).

Attention to Norway at the fair, promoting their own country. Captain Magnus Andersen had a copy built of the excavated Viking ship from Gokstad, but archaeologists were at first heavily against the idea of actually sailing the ship across the Atlantic, not being sure if the original ship was just ceremonial or actually seaworthy.

In less then a month, Andersen and his crew of 11 people crossed to Newfoundland. When they got familiar with the ship, they ‘‘were able to look at the ship’s movements and its capacities of enduring storms a bit more calm and with less preconceptions’’. The ship was very elastic but remained watertight. The proven seaworthiness was an important result of this excursion. The experiment resulted in information which could be compared to the archaeological remains of the Gokstad ship and other, later Viking Age ship finds.

The clear gap between archaeological scientists and craftsmen has unfortunately played a role in experimental archaeology ever since. An important problem is the loss of everyday knowledge - abilities which many people mastered three generations ago need now to be reinvented, through trials or experiments. Experience, therefore, plays an important role in experimental archaeology - not the obtaining of it, but the use.

Andersen’ expedition marked the start of a tradition of building ships, based on archaeological examples and sailing with them (Figure 2). Noteworthy are the dozens of travels by Thor Heyerdahl and Timothy Severin. At present, there are literally hundreds of such ships.

Patriotic elements, besides military themes, were often an important motive for experiments. That archaeology alone makes costly experiments like the construction of ships feasIble is a pity. However, relevance of both archaeology as a science and experiments to other areas of society is necessary for both to justify their existence. This, however, can also mean use and misuse of archaeology or experimental archaeology. Good examples can be noted from Germany, from the beginning of the twentieth century up to the fall of the Nazi Reich.

Already from 1897 onward, there were reconstruction works executed at the Saalburg in southern Germany. This used to be a Roman castellum at the Upper Germanic-Raetian border in the first to third century AD. In 1913 (just before World War I (WWI)), experiments were carried out here to build Roman defensive works out of wicker with replicas of Roman tools. The works were carried out by the Mainzer Pioneer Battalion and paid for by the emperor himself. The Saalburg is nowadays still the only fully reconstructed Roman castellum in the world. By rebuilding this, Emperor Wilhelm II followed a trend amongst nobility and the court and their interest for archaeology. As with the nineteenth century treasure rooms, nobility wanted to show the link of the mon-archs with history, and thus legitimize their position. The activities back in those days at Saalburg were not about the classic museum tasks - collecting, preserving, and presenting.

During the Nazi regime in Germany, archaeology and experimental archaeology were put to use in professional popularization and massive ideological exploitation in attempts to justify the Third Reich’s view of the world. The 1936 Berlin ‘hands-on’ exhibition Lebendige Vorzeit was a powerful tool in spreading the Nazi ideology, just like the open-air centers which were established across the Reich. The goal was not to serve science, but that the people start believing in the cultural level of their forefathers.

In the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, archaeologists looked for ‘living’ analogies to their excavated material culture. This practice is summarized under ethnoarchaeology (see Ethnoarchaeology). Archaeologists saw more resemblances between their forefathers and non-European, preindustrial societies than with themselves. The active colonization of areas outside Europe - or the more intensive use of these - in the nineteenth century enabled making anthropological observations easy. Sir John Lubbock was one of the first to suggest such anthropological observations in his book Pre-Historic Times as Illustrated by Ancient Remains and the Manners and Customs of Modern Savages (1865).

In California, at the end of the nineteenth century, a small group of native Americans, the Yahi, were trying to continue their way of life without modern influence. In 1865, most of them were slaughtered,

Figure 2 Preparations for putting the Viking ship replica to sea in Bergen, 1893. Bergen (1894).

In Rasmussen, viking fra Norge til Amerika,

And around the turn of the century their last camp was destroyed by White settlers. In 1911, the last surviving Yahi was ‘adopted’ by two anthropologists and was named Ishi, which in his own language simply meant ‘man’. In the following 5 years, he taught the anthropologists a wealth of things about his society, like hunting or fire making, things one would not be able to learn from simple excavations. Ishi made clear that it was not just about knowing how a technique needs to be applied, but an ample experience in using it is also required. With his death in 1916, a wealth of knowledge about the life of the indigenous people in North America disappeared.

By the end of the 1960s, ethnoarchaeology proved to still be useful as an eye opener for archaeologists. Yellen looked into what kind of faunal remains reach the archaeological record from known butchery sites of the African! Kung bushmen (see Butchery and Kill Sites). The anthropologist excavated some sites, together with the people actually forming those sites a few months earlier. It became clear how difficult it was to discern between natural and cultural factors for the appearance or disappearance of certain bone fragments. However, by making a difference between these two groups, one would better be able to describe the cultural factors. Simple culture-determined facts like how to cut meat and bones and which bones to take away from the site cannot be known to archaeologists, thus leaving a lot unexplainable. The !Kung for example remove the right ribs - not for cooking but to hang them from a tree. We cannot explain the archaeological record fully without knowing the cultural determinants.

Ethnoarchaeological observations are hardly ever comparable with archaeological observations at a 1:1 scale. This - and the fact that there are hardly any societies to be studied, undisturbed by industrial societies - elevates the role of the use of scripted analogies (experimental archaeology). The value of ethnoarchaeology lies in the fact that the people observed master their techniques quite well, this in contrast to most experimental archaeologists. The experience might as well hinder the one executing the experiment in not being able to adjust to the needs of the archaeologist, who wants to create an action which is as much as possible comparable to his or her archaeological theory and data and fits in the imagined cultural framework.

World History

World History