Figure 10.26: Dolmen, Sierra de Aracene, Spain. Source: Alberto Gonzalez

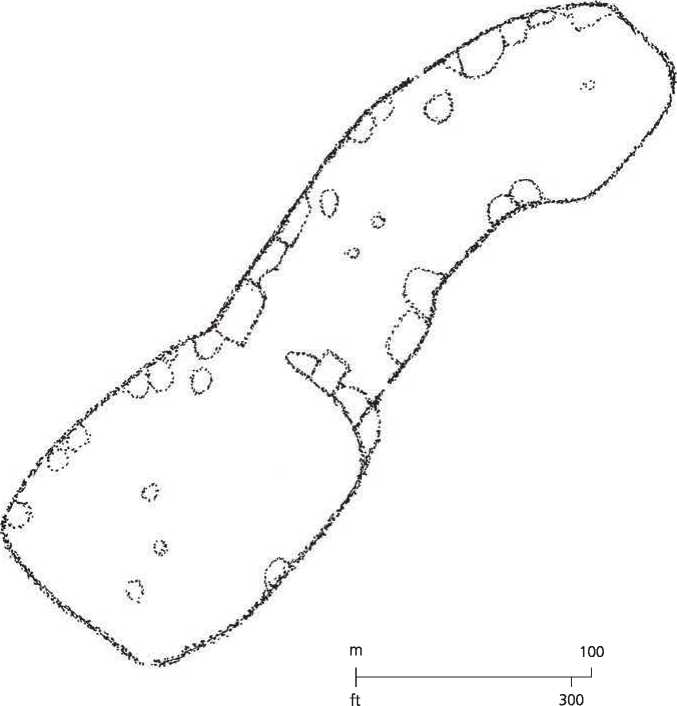

Around 4000 bce, if not earlier, the ideas and technology of farming, cattle raising, and monument building arrived in England and Ireland, forcing the resident population to make way for a group of people who chopped down forests for their fields and set up camps in the highlands for their animals. Such an enclosure can be seen at Rider’s Rings, sited on a ridge between two springs that had a 2-meter-thick wall with small internal spaces (Figure 10.27). The newcomers also began their quest for clay for their pottery as well as for flint, and soon numerous mines were in operation. In their heyday these mines produced prodigious amounts of rocks,

The largest being Grimes Graves. It was no informal affair, but a proper mine with shafts, supporting pillars and galleries deep below the ground. The flint was levered from the chalk in which it was embedded with picks made of antlers from a red deer. The black lustrous stone, known as floorstone, that was found there must have been considered particularly special, and most certainly mining activity went hand in hand with ritual activity.34 The axes made at these mines were not used as weapons, but to chop down trees. Ireland was also blessed with relatively rich copper deposits, allowing large quantities of bronze to be produced on the island. Copper was mined at Mount Gabriel, at Ross Island, and across the Irish Sea at Orme Copper mine, probably extracted by lighting flres inside the mine and then, when the mine walls had become hot, splashing them with water, thus shattering the ore, which could then be removed.

With the warm weather, warmer than today, many areas were soon transformed into thriving communities. Carrowmore in northwest Ireland was one of them, with a mixture of farming and pastureland that stretched 20 kilometers from a lake along a river down to Sligo Bay. From the start, it was also marked as a sacred landscape, with as many as two hundred tombs, dolmens, and stone circles, the earliest erected around 4700 bce. Almost all the burials are cremations, with most of the tombs in an area about a kilometer in extent north to south and about 600 meters across from east to west. The bones were disarticulated, meaning that they were deliberately mixed and sometimes sorted in particular ways so as to celebrate clan cohesion.35 Within this cluster of tombs, there was one in a large open space 34 meters in diameter that is known as Listoghil. It is also the only tomb that appears to have been decorated with

Figure 10.27: Rider's Rings. Source: Mark Jarzombek/Timothy Deerhill, Prehistoric Britain from the Air (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1996), 89.

Carvings on its sill and capstone. It was built with a good deal of regularity with a.7-meter thick limestone cap, unlike the granite of the other tombs, and covered with a mound of stones (now partially uncovered for display reasons).

Since portal tombs can be found in eastern and northern Ireland, as well as in the headlands of England facing Ireland, this zone clearly constituted a single cultural horizon. The Poulnabrone Dolmen (3800 to 3200 bce) is certainly a magnificent example. It sits prominently on an exposed limestone outcropping. The 4-by-3-meter flat capstone angles from the portals down to the rear. Inside there was a shallow grave containing reburied bones. The most likely scenario is that bodies were buried at another location, then ritualistically dug up and transferred into the dolmen. This must have been done with much care, because of the large amounts of small bones found in the chamber that would have taken time to remove from the primary inhumation before being placed in the grave in the dolmen.

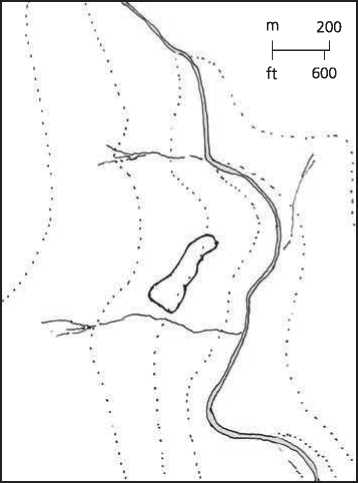

The most common tomb in the north of Ireland, and unique to Ireland, is the so-called Court Tomb. Its distinctive feature is an uncovered area in front of a mound, usually along the narrow end, called a court, through which one has to pass to gain access to the tomb proper. There are over three hundred such tombs in Ireland, found mainly in the upper half of the country. The tombs usually hold several chambers connected to a passageway. Audleystown Court Tomb has courts on both ends (Figure 10.28). The mound is trapezoidal in plan and orientated northeast/southwest, with the wider end facing southwest. It is lined at its base with a drystone wall of shale slabs buttressed on the outside by shale and red soil. Each court opens to a four-chambered passage. The burial method here was cremation. The inner two chambers of the northeastern gallery had a fire pit where the cremation took place. The remains of

Figure 10.28: Audleystown Court Tomb, Ireland. Source: © Ardfern (Http://creativecommons. org/ licenses/by-sa/3.0/deed. en)

About thirty-four people were found in the remaining chambers, comprising men, women, and children. They were either inhumed, partially burnt, or fully cremated. Magheraghanrush, or Deerpark Court Tomb, as it is also known, is somewhat unusual in that its court is in the middle of the composition. It is a 15-meter-long oval with a single gallery at the west end and two double-chamber galleries at the east end with a passage entrance on the south side. The ends were covered by a rectangular cairn of stones.

World History

World History