The Pyu civilization of Central Burma was one of the earliest in Southeast Asia to adopt Indian alphabets and Buddhist thought. Pyu archaeological evidence shows a complex union and interaction of pre-Buddhist and Buddhist ritual similar to that of Andhra. The earliest Pyu fragmentary inscriptions show a knowledge of Indian palaeography from c. first century CE mixed with letter (aksara) types that date from the third century. From at least the first century BCE, however, there had been Pyu technical borrowings from India, revealed especially in brick making of Mauryan and Sunga types, without any sign of the adoption of Buddhism. Instead the earliest ceremonial buildings in the cities of the Pyu were large brick and timber halls devoted to multiple burials, probably of rulers and their consorts, cremated and installed in groups in urns that replicated in terra cotta the shape and often the dsicor of bronze drums.

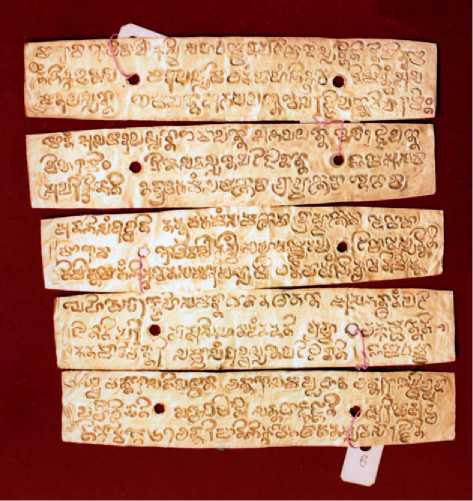

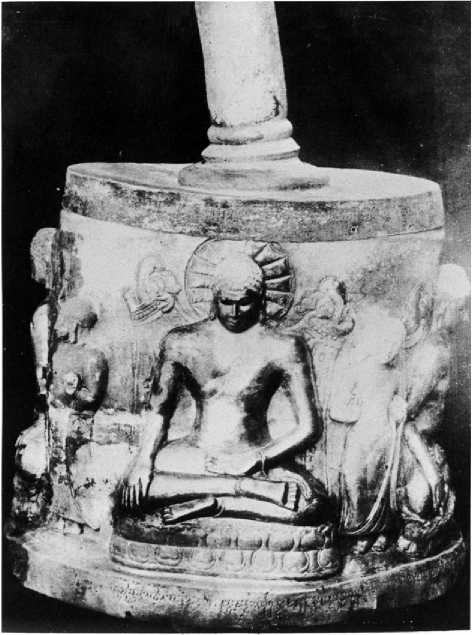

From the third century CE onwards there is abundant evidence of the adoption of Buddhism among the Pyu and the construction of monumental complexes of stupa, shrine, and monastic cells that reveal the influences of Andhra assimilated to a local style. At the same time, the Pyu tradition of urn burials inside and in direct proximity to brick monuments persisted in the context of a flourishing Buddhist civilization up to the ninth century and possibly longer. Indeed Buddhist archaeological finds in the major Pyu urban sites, Beikthano, Halin, and Sri Ksetra, have contributed precious insights to our understanding of the history of Buddhism in general. For instance, a complete replica of a palm leaf manuscript in solid gold (Figure 7) was found in the relic chamber of a ruined stupa mound (the Khin Ba mound) in Sri Ksetra, dating from c. mid-fifth to early sixth century CE. This relic chamber also contained one of the largest reliquaries ever found, made of silver partly gilded, and decorated in high relief with some of the earliest Buddha images of Southeast Asia (Figure 8), and the largest treasure of gold and silver objects ever found in a relic chamber in South or Southeast Asia, The manuscript consisted of 18 gold leaves inscribed with excerpts of varying lengths from eight core texts of the Pali canon, two end covers in gold and the whole was bound together by gold wires.

These samples of canonical Pali are considered to be the oldest and certainly the most extensive surviving examples in the world so far known. They have

Figure 6 Panoramic view of Pagan, the largest ancient Buddhist city, tenth to thirteenth century CE.

Figure 7 The golden Pali manuscript from Sri Ksetra. By courtesy of the Archaeological Department Myanmar, fifth-sixth century CE.

Figure 8 The great silver reliquary from Sri Ksetra. By courtesy of the Archaeological Department Myanmar, fifth to sixth century CE.

The aDditional value of a securely identified archaeological and chronological context. For these reasons, they not only provide a privileged glimpse of the extent of Buddhist knowledge outside India in this non-Indic city at this time, but the characteristics of the palaeography indicate that the Andhra coast was the hearth of the Buddhist learning of all but one of the monks who inscribed their chosen excerpts on the gold leaves. The exerpts also provide a unique basis for assessing the integrity with which the same Pali texts were preserved in the largely oral tradition in Sri Lanka and elsewhere and collected in the nineteenth century. Pali texts in Thailand of c. sixth-seventh century age, which reflect the existence of early Buddhist cultures there as well, are short and fragmentary inscriptions. Though valuable evidence, they cannot provide such extensive insights into the state of Buddhist culture in Thailand at that time. It is arresting to note that the wider context of Sri Ksetra reveals the largest burial fields of pre-Islamic Southeast Asia and includes urn burials placed inside major Buddhist shrines inside the city, buried under their paved courtyards, as well as thousands of urn burials encased in small funerary stupas and large stepped burial terraces outside the city walls.

Thus in its spread outside the area of its origin in Northeast India, Buddhism appears to have preserved its precious core message while presenting porous boundaries to the pre-existing cultures it encountered. Locally specific styles and practices emerged early to diversify and enrich the appeal of the Buddhist eucumene.

See also: Asia, South: Ganges Valley; Indus Civilization; Megaliths.

World History

World History