Literary tradition has it that the Romans expelled the last Etruscan king, Tarquinius the Proud, and established the Republic in 509 BC. If the temple of the Capitol triad seems to have been inaugurated at that period indeed, and the first lists of consuls appear contemporaneously, the archaeological remains suggest that a much more violent crisis happened in the middle of the fifth century, with important fire tracks on several public buildings, such as the Regia and the comitium, followed by the reconstruction of a part of the forum. Once again, more than a proper ‘revolution’, it seems that the political organization of the city has progressively changed all

Through the first half of the fifth century, which might reflect the different steps of the conflict between patricians and plebeians, and the fear of the return of kings in Rome, probably more and more stigmatized throughout ages.

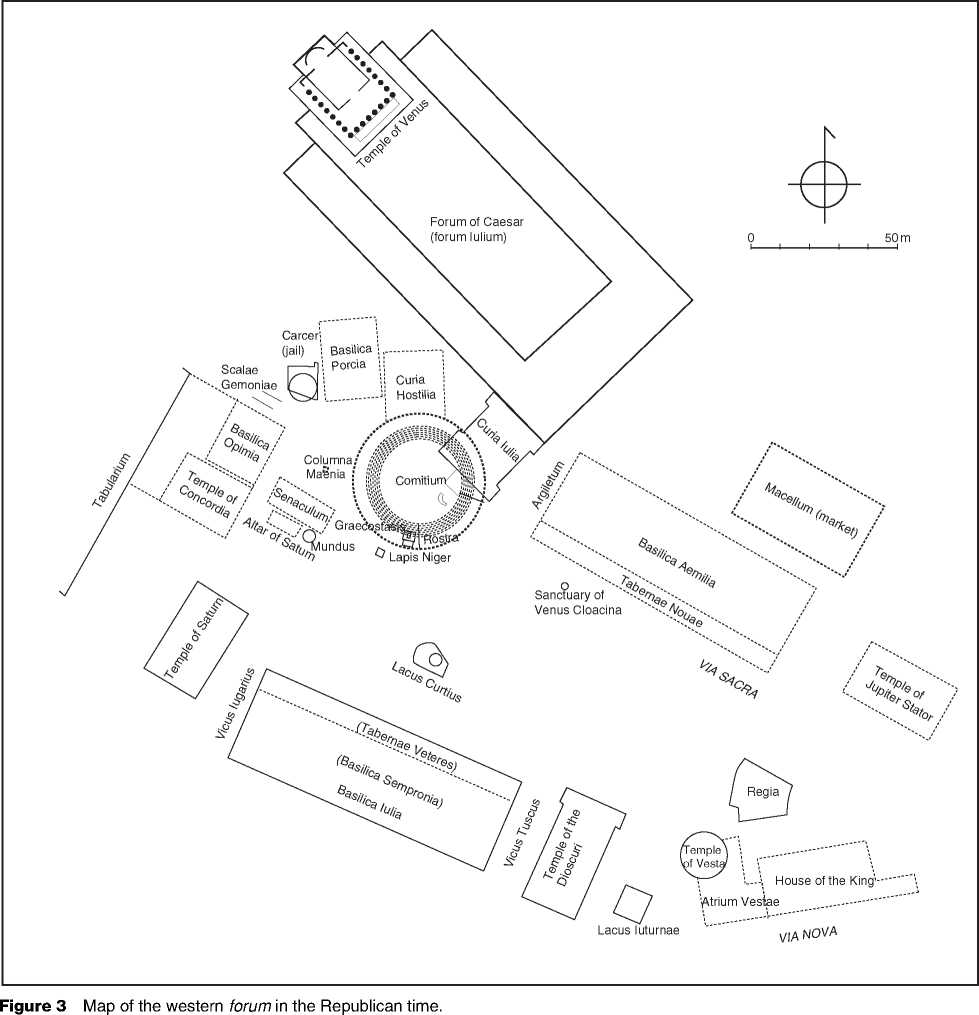

The forum Romanum

From that time dates back a reorganization of the city, and above all of the forum, that was used as the politic, economic, and symbolic center of Rome (Figure 3). Initially (probably as soon as the late sixth century), the area of the forum was roughly divided into two parts, distinguishing a northern zone around the comi-tium for public activities, and the forum as such, the market place in the southern part. Progressively, the part devoted to politics, in a broad sense, tended to monopolize the entire area: besides the political spaces as such, this normally included the religious sphere, which was absolutely inseparable from the civic activities. As for the economic activities, most of the cumbersome markets were moved to the Tiber’s bank, on the forum boarium, holitorium, and piscarium,

Figure 4 Archaic podium of the temple of Jupiter Capitolinus.

Respectively, for the trade of livestock, vegetables, and fish, whereas prestigious business (banking, jewellery, perfume) were maintained around the macellum, divided into shops (tabernae), from the balconies of which people could look at the gladiators’ fights, still taking place on the forum place up to the end of the Republic, and sponsored by the politics.

As a matter of fact, one relevant feature of the Republican time was the competition between the members of the new aristocracy (the nobilitas, composed of both patricians and plebeians), physically expressed by the construction of different monuments glorifying the rulers and their families, as they paid, with the profits of looting, to build, restore, extend, and embellish the public buildings. This implies that most of those buildings were called after a leader - except the temples named after the divinity to which they were devoted - and that the forum was subjected to an increasing competition of that sort of evergetism, up to an actual saturation. At the end of the Republic, the only way to carry on this escalation was to extend the forum, which meant building new ones: the first initiative in that sense was used by Cesar, imitated on a larger scale by Augustus, Vespasian, and Trajan. The original Republican forum went on to be called the ‘Roman forum’, whereas the new ones got the name of each Emperor, known at once as the ‘imperial forums’ (Figure 5).

Archaeologically, the forum Romanum is better known from the fourth century (as Rome was restored after the Gallic siege of 390), and mainly from the second century BC: after the victory over Carthage, the rule of Rome on the Mediterranean led to a rapid accumulation of wealth, and an important embellishment of the city - starting with the forum, as the most obvious politic symbol of the power of Rome. Combined with the competition between the rulers, Republican Rome displayed above all the image of its triumph on the Greek and barbarian worlds, in terms of military victories (triumphal arches, euocatio of the enemies main divinities) and looting (mainly sculptures and paintings), whereas the influence of Greek art and technology was to change definitely the shape of the city. However, throughout the Republic, the overall organization of the forum did not fundamentally change: the key buildings remained roughly the same, so as to be reproduced in other cities under Roman power, specifically most of the colonies (see Asia, West: Roman Eastern Colonies; Europe, South: Greece).

The comitium area Among these buildings should be first counted the complex of the comitium, made up of the comitium itself, the curia, the Rostra platform, and the Graecostasis (‘platform for the Greeks’). The whole represents the architectural image of the working Republic, politically and judiciary: the people used to assemble on the place at the center of the comitium, the Senate usually in the curia, and the magistrates to speak from the Rostra (whereas the foreign representatives could contribute to the Senate meetings from the Graecostasis).

The comitium existed since the royal period, but its Republican shape was adopted either at the end of the fourth or in the middle of the third century BC: probably under the influence of the Greek public ekklesiasteria, it was designed as a circle inscribed inside a square, with internal terraces, while, as an inaugurated templum, it was oriented following the cardinal points. As a matter of fact, the first

Roman colonies designed in the first third century - Alba Fucens (301), Cosa and Paestum (273) - adopted such a circular structure as the center of their own political lives.

South of the Roman comitium had been set up, at the very beginning of the Republic, the raised platform for the orators, magistrates, and lawyers, named Rostra (‘ship-rams’ driven into a column on the platform) after the naval victory of Rome over the Latin people, off Antium, in 338. Cesar moved it westwards when he extended the forum, purely and simply destroyed the Graecostasis and turned the curia Hostilia into a temple to Felicitas, as he was to build a new curia named after his family, the curia lulia (Figure 3): a high rectangular building (corresponding to the proportions prescribed by the Caesarean architect Vitruvius) subdivided inside into three longitudinal sectors to welcome the senators. These modifications, directly linked to the topographical move of the center, were obviously highly symbolic: notably, that was the way to turn the Rostra from the curia to the forum, that is to say the magistrates, from the Senate to the people, in accordance with Cesar’s popular politics.

Shaping the forum The last generic building of the Roman forum was the basilica (‘royal building’, named after the Hellenistic kingdoms’ architecture adopted in Rome at the end of the third century BC). It was a large covered space designed as a substitute for the open space of the forum when the weather did not allow its normal activities - economic, politic, and judiciary. The structure of the basilica, usually subdivided into three parallel aisles by two central colonnades, has been adopted by Christian architecture when building churches which maintained the terminology.

During the Roman Republic, texts mention at least four basilicas: Porcia, Aemilia, Sempronia, Opimia, before the edification of the Caesarean basilica lulia. The latter is an extension of the basilica Sempronia, south of the comitium area and the forum place, and appears much richer than the Republican ones in terms of architecture and decoration, even just the podium remains nowadays: 101 x 49 m (including the previous basilica and the adjacent ‘old shops’), five aisles bordered by porticos on two levels of arches, and internal temporary subdivisions that allowed judgement in several trials contemporaneously.

One of the urban functions of those large and regular buildings was to unify and close the forum, that is to say to create a coherent complex where the gradual set-up of the place tended to appear anarchic. It is no accident that Cesar proceeded to the restoration of the basilica Aemilia, north of the forum, contemporaneously with the construction of the basilica lulia, and of its own forum, with all the modifications in the comitium area above mentioned. When he finally opened the northwestern corner of the forum Romanum in 46 to set up the forum Iulium, he bordered it directly with a portico on three sides, and at the center of it a temple to his patron Venus Genitrix, and a bronze equestrian statue of himself (Figure 5).

The Republican place had already been closed west, against the Capitol, with the monumental Tabularium (where were kept the State archives, the tabulae), by Quintus Lutatius Catulus in 78: a long gallery on three levels, inspired by the architectural development of Latial sanctuaries which would become a model for other Roman buildings (such as the theater of Pompey, the Coliseum, or the Trajan’s markets), served to link the aerarium (‘bronze treasure’) and the temple of Saturn to the coins workshop, close to the temple of Juno Moneta on the Capitoline Hill.

The Republican shape of the forum Romanum was, lastly, definitely determined by a number of temples and shrines, and of honorific monuments to the glory of the rulers. Once again, each and every aspect was symbolically inextricable: a temple dedicated to a divinity who helped the Romans to win a victory (often a deified human quality) celebrated at the same time the god, the power of Rome and the action of the general and his family. Little remains of the numerous Republican sanctuaries of the forum which were so many testimonies to Roman history, as they have been continuously restored and reused during the Empire. Among them might notably be named, in addition to the royal shrines still in use throughout the Republic (sanctuary of Venus Cloacina, altar of Saturn, temple of Vesta, mundus - the navel of the City), the temples of Saturn and of the Dioscuri Castor and Pollux (early fifth century BC, restored both several times), the temple of the Concord (fourth or third century). But the Republican temples are best known, thanks to the temples on the forum boarium (to Portunus and Hercules Victor) and on the area sacra of the Campus Martius.

The Campus Martius (‘Field of Mars’)

Topographically, the campus Martius is the plain included between the Capitol, the Tiber, the Quirinal, and the Pincio, but the name usually refers to the western part of it, delimited by the via Flaminia (Figure 2): outside the pomerium, it is a public area (since, according to the tradition, it was the property of Tarquinius before being seized by the Republican State), devoted to military exercises, sportive games (such as horses races), and some political assemblies (notably the elections of magistrates in the saepta, the ‘vote enclosure’), that is to say to activities that required a large space in which to gather the Roman people, armed and voting (theoretically synonymous at that time).

Unlike the center of the city, the campus Martins was for a long time an open space rather free of constructions: this explains that, from the second century BC, it became a proper ‘laboratory of urbanism’ (P. Gros), progressively extended northwards. Roughly, four archaeological phases are well identified: the sanctuaries of the mid-Republic (fourth to third century BC), the Hellenistic constructions in the area of the circus Flaminius (second to first century BC), the Augustan extension northwards, and the Imperial modifications (essentially during Domitian, Hadrian, and the Antonin Emperors’ reigns, from the end of the first century to the end of the second century AD).

The area sacra of the Largo Argentina The four temples of the sacred area, emphasized, thanks to the preserved zone in the middle of the Largo Argentina (Figure 6), give the best idea of the evolution of Republican religious architecture (even if all of them have been several times restored, particularly after the fire of AD 80). Built between early third century and late second century BC, it had not been monumentalized as a coherent complex before the mid-second century, unified by a paving between the temples. Now the architecture and decoration of their first phases (sometimes found reused in the Late Republican or Early Imperial restorations) progressively go from Latial traditions (shared with south Etruria) to Hellenistic ones, typically with the circular neoclassic temple B (Figure 7).

At the same time, this religious area reveals itself to be very coherent with the entire zone: the involved divinities (convincingly identified by F. Coarelli as Feronia, Juturna, the Lares Permarini, and Fortuna Huiusce Diei, 'the Fortune of today’) were linked to the provision of supplies, thanks to marine and fluvial transport, related to the plebeian connotation of this part of the Campus Martius, particularly since the construction of the circus Flaminius in 221, competing with the traditional circus Maximus.

Yet, from the second century BC, the Field of Mars was to become, even more than the forum, the scene of intense rivalry between the leading families who found enough room, and fewer restrictions than inside the pomerium, to conceive huge constructions, such as porticos and theaters. The most relevant example is the complex of Pompey, directly west of the area sacra, dedicated after his triumph of 61: at the top of the theater stood the temple of his patron Venus Victrix (the terraces of the first serving as a scale for the second, allowing to get round the interdiction to construct a permanent show building), whereas a squared portico, adjacent to the theater, adorned by a rich collection of artworks and finally devoted to Pompey, was closed by a new curia (in which Cesar was murdered 10 years later). Despite the scarcity of material evidence (the shape of the theater is readable in the layout of modern streets), this complex is a proper summary of the changing conception of the state, physically and symbolically reflected in the city, to the glory of a man. Cesar was to magnify the same movement when he prematurely died: August pursued his projects and extended them to definitively change the face of Rome.

World History

World History