Inca administrators governed the most directly integrated provinces - those located beyond the boundaries of the imperial heartland but generally in highland valleys to the northwest and southeast - by means of decimal administration that was imposed when a province was (re)conquered. The decimal hierarchy consisted of nested administrative positions (kuraka) staffed by local elites and supervised by Inca governors and inspectors. Subject populations provided labor service, and Inca officials monitored population levels and service requirements, punishing a local kuraka who failed to meet state demands. Service was worked in rounds by a proportion of the population, and it appears that local elites were responsible for deciding who would satisfy a given service category. Canny local elites were able to increase their wealth and prominence through the implementation of imperial labor demands, organizing caravan transport and pursuing their own exchanges and resource extraction alongside the imperial system.

While provincial decimal officials managed local labor tribute mobilization, the principal administrative activities took place in Inca cities, which reproduced essential open spaces and administrative and religious institutions that moderated encounters between Inca administrators and local elites. Decimal

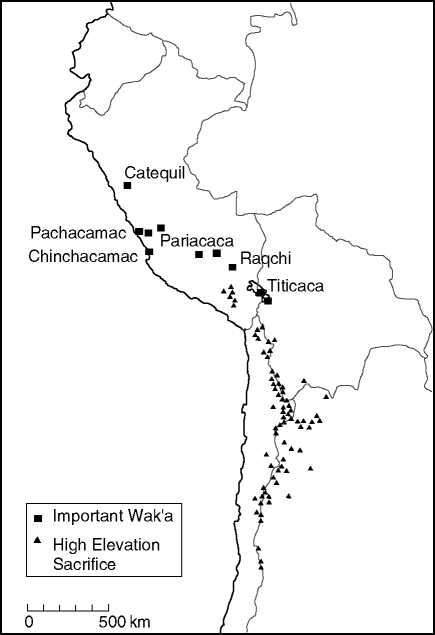

Figure 3 Religious integration in the Inca empire. Information on high elevation sacrifices from D’Attroy, TN (2002).

Administration appears to have been linked to population movement between the imperial heartland and provinces - Quechua-speaking colonists from Cusco’s Inca-of-Privilege groups were settled into some provincial regions to facilitate consolidation strategies, while provincial populations were resettled as labor colonists and retainers.

Coastal regions do not appear to have been as affected by decimal reorganization or obligate resettlement. Ethnic Incas were not heavily settled into coastal state territories, nor did coastal polities provide large populations of mitmaqkuna or yanakuna for service in the imperial heartland. Craft specialists (e. g., Chimti silversmiths) are known to have been relocated to the capital, and the production and distribution of craft goods and wealth objects changed in coastal regions under Inca governance. According to some documents, Inca administration on the coast was limited to state interests while the local political economy remained under the existing ruler. Imperial officials were established at important coastal centers and looked after whatever new agricultural lands could be developed - particularly in the mid - and upper-valley areas - as well as retainers and female ritual specialists (mamakuna) placed in the valley. Coastal elites tended not to control significant territories beyond what was needed to protect irrigation intakes that watered the flood plain of their valleys, and the Incas were able to invest in economic intensification further inland, employing strategies similar to those already described for highland valleys.

Patterns of decimal administration in highland provinces and parallel administrative structures in coastal states indicate that the fiction of local economic autonomy was important throughout the empire, while the Inca state invested labor tribute in improving farmland and developing intensive agriculture in areas that were unused or under-utilized. Such a system reduced the prospect of conflict during the initial annexation of a new province, but gradually made local elites redundant or dependent on the state for their status and its communication. Provincial rebellions were common, particularly after an Inca ruler died, and local uprisings justified the state in confiscating resources and imposing a more extractive administrative apparatus.

The degree of military investment on the imperial frontier indicates that the Incas were in no hurry to consolidate administration along the coast, but also suggests an important development in imperial strategies. A direct occupation was required in the highland valleys of the frontier zones, but the Incas left local exchange networks in place in some areas to acquire lowland goods whose provenance lay outside of direct administrative control. Highland groups like the Caiaaris were massively reorganized, with large proportions of the population resettled as mitmaq-kuna, brought to Cusco as yanakuna, or pressed into more or less permanent military service.

Conquest and Colonialism

The documentary evidence provides our most complete means of reconstructing the Spanish Conquest and imposition of colonial administration in Inca territory. Eyewitness accounts present important discrepancies, and, with the exception of the 1570 account of Titu Cusi Yupanqui, the Andean voice is almost completely absent in the reconstruction of the story. Although the story of the Pizarro invasion was told by Spaniards, administrative documents from the Cusco region provide important details for reconstructing the decades-long process of administrative reorganization that transformed the Inca imperial heartland into a Spanish provincial region.

World History

World History