In pre-Columbian Mesoamerica, what is now southern Mexico and the countries of Central America, as many as 13-15 different writing systems had been developed by AD 900. They include the Zapotec, the Maya (in several stages), the Mixtec, the Aztec, and the Epi-Olmec. Archaeological discoveries have demonstrated that all of them were used around the region for a substantial time span. The earliest of these, the Zapo-tec, emerged around 500 BC, and as late as the seventeenth century AD the Aztec and Maya writing systems were still being used by remnants of the civilization.

It is thought that writing emerged in Mesoamerica at the early stages of state formation, around AD 600 as a tool that enabled competition between local rulers. Writing was used to establish royal lineages, mark auspicious birth dates, identify vanquished rivals, and mark political territory, as well as important moments in rulers’ lives, such as marriages, births, and deaths. Early scholarship on Mesoameri-can writing held that it amounted to astronomical and calendric record keeping, and did not represent linguistic units. Therefore, it was believed that Meso-american writing did not contain historical texts. This

Began to change in the 1970s, when the phonetic components of these writing systems, particularly Maya, were finally recognized. Since then, major work deciphering Mesoamerican writing has taken place, giving us unprecedented access to written pre-Columbian history.

The most visible and best-known example of Mesoamerican writing is Maya, which flourished from AD 250 to 900. Precursors of Maya writing have been discovered that date to 300 to 200 BC. Examples of Maya writing survive mainly on freestanding stone monoliths known as stelae and on the stone interiors of palaces and temples, as well as on ceramics. Maya was also written on books made from bark paper or deer paper as well. Four Maya codices are known to exist, named for the cities in which they now reside: the Dresden codex, the Madrid codex, the Paris codex, and the Grolier codex.

All Mesoamerican writing was heterogeneous, in that each system mixed iconic, logographic, ideographic, and phonetic elements. Over the centuries, each system varied in the proportions of each element used. Though it is supposed that iconic (or picto-graphic) signs were the earliest to be used, not all of the systems evolved unilinearly toward the representation of linguistic units.

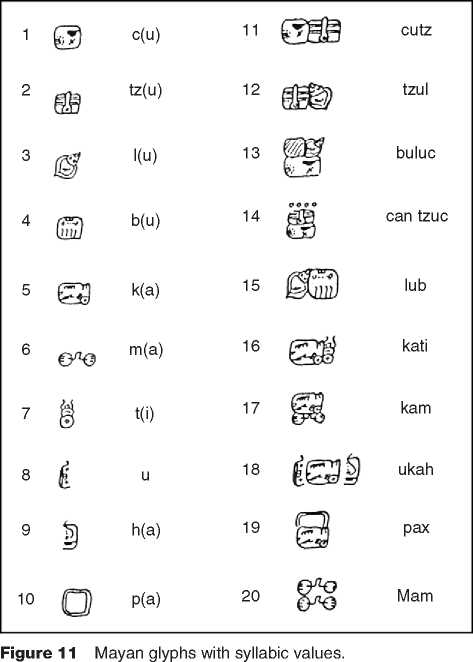

In Maya, signs were known as glyphs. About 1000 Mayan glyphs are known to exist, though only 600 glyphs were in use at any particular time. Though a small fraction of these signs represented syllables of the language, Maya has the highest number of known phonetic glyphs of any Mesoamerican writing. Most of the remaining glyphs represent royal names. As a result of phoneticization, nouns, verbs, adjective and adverbs can be read in Maya texts. It is supposed that the glyphs written between AD 250 and 900 represent an older form of a Cholan language, perhaps Chorti or its ancestor, Cholti. (Figure 11).

On the stelae, the glyphs were always written in paired vertical stacks and read top to bottom, left to right, in a zigzag fashion. Each glyph organizes several smaller elements known as graphemes and contains a main grapheme with one or more diacritics. The diacritics can appear to the left, right, top or bottom of the main symbol. The sequences of graphemes in a glyph are read, more or less, from the upper left corner to the lower right.

Glyphs represent words, morphemes (or basic units of words), syllables (consonant + vowel sequences), as well as determinatives. Maya scribes used the same signs to represent different words and represented the same word with different signs. Unlike in modern alphabets, this polyvalence offered opportunities for a visual poetics of writing. Because there was no set standard for glyph construction, writers often

Presented the same word in many different ways, even in the same texts, and writers seemed to take pleasure in creating these variants.

Despite its prominence, Maya writing was not the oldest Mesoamerican writing. The earliest undisputed writing in the New World is Zapotec writing, which was first developed in Oaxaca between 600 and 400 BC. It was used until AD 1000. Zapotec glyphs, which represent an ancient version of the Zapotec language that has not been reconstructed, represented personage names, nouns, verbs, and place names. The body of known glyphs in Zapotec is very small, only about 100. Many appear to represent words; a few represent syllables. It is not known how many are purely phonetic. It is thought that Zapotec writing marked the evolution beyond a purely pictographic form that could not represent place names or dates. The number of texts containing glyphs is also very small, only about 570.

Were Maya and Zapotec writing related to each other? Though the two cultures were in contact with each other (for instance, we know from archaeological evidence that they exchanged ceremonial ceramics), their writing systems differed from each other. The body of individual glyphs differ, as well as the determinatives, which reflects the fact that the two writing systems were used for unrelated languages. Nevertheless, there are three scenarios for the relationship between Maya and Zapotec writing: (1) they represented two independent but parallel developments; (2) they had a common origin and evolved unique characteristics later; and (3) through cultural contact, one group borrowed writing from the other. The archaeological evidence that may provide definitive answers has not yet been discovered.

Another writing system that predates the Maya is called Isthmian (also called Epi-Olmec or the La Mojarra script). Only five legible texts have been discovered, the most recent in 2004. Though scholars generally agree that the language represented by the text is an archaic form of Zoquean, efforts to decipher the texts are in doubt.

The earliest writings that are recognizably antecedent to later scripts date to around 650 BC in the states of Tabasco. In 2002 archaeologists M. Pohl,

K. Pope, and C. von Nagy announced the discovery of a roller stamp and plaques with glyphs, which were found near the Olmec site of La Venta in Tabasco. Evidence that the glyphs count as writing and not visual representation comes the inclusion of a frequent element in Mesoamerican writing systems, a shape coming from the mouths of figures called a ‘speech scroll’. The inclusion of the speech scroll may signify that the glyphs they contain represent spoken language.

Two forms of writing in Mesoamerica a rose after the Classic Maya period, Mixtec and Aztec, about AD 1100 to 1600. In contrast to Maya, these writing systems were less phonetic and more pictographic. As Marcus describes the difference:

‘‘Whereas the Classic Maya scribe could use a pure hieroglyphic text to state that a ruler had been born, married, acceded to the throne, conquered a rival, captured a prisoner, and died, the painter of a Postclassic Mixtec codex might have to use a whole series of captioned drawings to show that many events.’’

This is significant because it demonstrates that writing systems do not necessarily evolve in the direction of increasing phoneticization; rather, the level of linguistic representation reflects the uses to which the script is put. Mixtec and Aztec were still in use during the early colonial period, so these texts are largest in number and have been deciphered. These texts do not tend to contain only hieroglyphic signs but mix pictures with labels for names, dates, places, and titles.

Archaeological work continues to play an important role in our knowledge about Mesoamerican writing, though the relationships among archaeologists and epigraphers (who work to decipher the glyphs) have been fraught. Because the known Mesoa-merican texts deal mainly with royals, the decipherment of these texts leaves unanswered questions about the common people, which excavations are better equipped to answer. On the other hand, decipherment and the linguistic knowledge it deploys has produced significant advances in our understanding of these civilizations.

See also: Americas, Central: Classic Period of Meso-america, the Maya; Postclassic Cultures of Mesoamerica; The Olmec and their Contemporaries; Asia, East: Chinese Civilization; Asia, West: Archaeology of the Near East: The Levant; Mesopotamia, Sumer, and Akkad.

World History

World History