Taxonomies are ways of organizing the natural world. Because taxonomies reflect scientists’ understanding of the evolutionary relationships among living things, these classificatory systems are continually under construction. With new scientific discoveries, taxonomic categories have

Nocturnal Active at night and at rest during the day.

Arboreal Living in the trees.

Diurnal Active during the day and at rest at night.

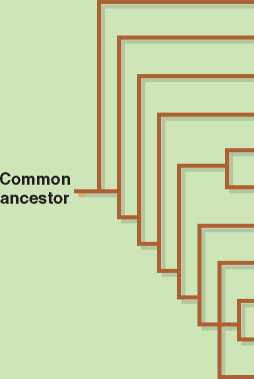

Two Alternative Taxonomies for the Primate Order: Differing Placement of Tarsiers

To be redrawn, and scientists often disagree about these categorical distinctions.

There are two hot spots in the classification of primates where scientists argue for alternate taxonomies: one at the level of dividing the primate order into two suborders and the other at the level of the human family and subfamily. In both cases, the older classificatory systems, dating back to the time of Linnaeus, are based on shared visible physical characteristics. By contrast, the newer taxonomic systems depend upon genetic analyses. Molecular evidence has confirmed the close relationship between humans and other primates, but genetic comparisons have also challenged evolutionary relationships that had been inferred from physical characteristics. Laboratory methods involving genetic comparisons range from scanning species’ entire genomes to comparing the precise sequences of base pairs in DNA, RNA, or amino acids in proteins.

Both genetic and morphological (body form and structure) data are useful. Biologists refer to the overall similarity of body plans within taxonomic groupings as a grade. The examination of shared sequences of DNA and RNA allows

Grade A general level of biological organization seen among a group of species; useful for constructing evolutionary relationships.

Clade A taxonomic grouping that contains a single common ancestor and all of its descendants.

Prosimii A suborder of the primates that includes lemurs, lorises, and tarsiers.

Anthropoidea A suborder of the primates that includes New World monkeys, Old World monkeys, and apes (including humans).

Researchers to establish a clade, a taxonomic grouping that contains a single common ancestor and all of its descendants. Genetic analyses allow for precise quantification, but it is not always clear what the numbers mean (recall the Original Study from Chapter 2). When dealing with fossil specimens, paleoanthropologists begin their analyses by comparing the specific shape and size of the bones with which they work.

The Linnaean system divides primates into two suborders: the Prosimii (from the Latin for “before monkeys”), which includes lemurs, lorises, and tarsiers, and the Anthropoidea (from the Greek for “humanlike”), which includes monkeys, apes, and humans. The prosimians have also been called the lower primates because they resemble the earliest fossil primates. On the whole, most prosimians are cat-sized or smaller, although some larger forms existed in the past. The prosimians also retain certain features common among nonprimate mammals that are not retained by the anthropoids, such as claws and moist, naked skin on their noses.

In Asia and Africa, all prosimians are nocturnal and arboreal creatures—again, like the fossil primates. The isolated but large island of Madagascar, off the coast of Africa, however, is home to a variety of diurnal ground-dwelling prosimians. In the rest of the world, the diurnal primates are all anthropoids. This group is sometimes called the higher primates, because they appeared later in evolutionary history and because of a lingering belief that the group including humans was more “evolved.” From a contemporary biological perspective, no species is more evolved than any other.

Molecular evidence led to the proposal of a new primate taxonomy (Table 3.1). A close genetic relationship was discovered between the tarsiers—nocturnal tree dwellers who resemble lemurs and lorises—and monkeys

Figure 3.3 Based on molecular evidence, a relationship can be established among various primate groups. This evidence shows that tarsiers are more closely related to monkeys and apes than to the lemurs and lorises that they resemble physically. Present thinking is that the split between the human and African ape lines took place between 5 and 8 million years ago.

And apes.1 The taxonomic scheme reflecting this genetic relationship places lemurs and lorises in the suborder Strepsirhini (from the Greek for “turned nose”). In turn, the suborder Haplorhini (Greek for “simple nose”) contains the tarsiers, monkeys, and apes. Tarsiers are separated from monkeys and apes at the infraorder level in this taxonomic scheme. Although this classificatory scheme accurately reflects genetic relationships, comparisons between grades, or general levels of organization, in the older prosimian and anthropoid classification make more sense when examining morphology and lifeways.

Using the older taxonomic scheme, the anthropoid suborder is further divided into two infraorders: the Platyrrhini, or New World monkeys, and the Catarrhini, consisting of the superfamilies Cercopithecoidea (Old World monkeys) and Hominoidea (apes). Although the terms New World and Old World reflect a Eurocentric vision of history (whereby the Americas were considered new only to European explorers and not to the indigenous people already living there), these terms have evolutionary and geologic relevance with respect to primates, as we will see in Chapter 6. Old World monkeys and apes, including humans, have a 40-million-year shared evolutionary history in Africa distinct from the course taken by anthropoid primates in the tropical Americas. “Old World” in this context represents the evolutionary origins of anthropoid primates rather than a political or historical focus on Europe.

In terms of human evolution, however, most taxonomic controversy derives from relationships established by the molecular evidence among the hominoids. Humans are placed in the hominoid or ape superfamily—with gibbons, siamangs, orangutans, gorillas, chimpanzees, and bonobos—due to physical similarities such as broad shoulders, absent tail, and long arms. Human characteristics such as bipedalism (walking on two legs) and culture led scientists to think that all the other apes were more closely related to one another than any of them were to humans. Thus humans and their ancestors were classified in the hominid family to distinguish them from the other apes.

Advances in molecular analysis of blood proteins and DNA later demonstrated that humans are more closely related to African apes (chimps, bonobos, and gorillas) than we are to orangutans and the smaller apes (siamangs and gibbons). Some scientists then proposed that African apes should be included in the hominid family, with humans and their ancestors distinguished from the other African hominoids at the taxonomic level of subfamily, as homi-nins (Figure 3.3).

Gorillas, they differ as to whether they use the term hom-inid or hominin to describe the taxonomic grouping of humans and their ancestors. Museum displays and much of the popular press tend to retain the old term hominid, emphasizing the visible differences between humans and the other African apes. Scientists and publications using hominin (such as National Geographic) are emphasizing the importance of genetics in establishing relationships among species. These word choices are more than

Strepsirhini In the alternate primate taxonomy, the suborder that includes the lemurs and lorises without the tarsiers. Haplorhini In the alternate primate taxonomy, the suborder that includes tarsiers, monkeys, apes, and humans.

Platyrrhini A primate infraorder that includes New World monkeys.

Catarrhini A primate infraorder that includes Old World monkeys, apes, and humans.

Hominoid The taxonomic division superfamily within the Old World primates that includes gibbons, siamangs, orangutans, gorillas, chimpanzees, bonobos, and humans. hominid African hominoid family that includes humans and their ancestors. Some scientists, recognizing the close relationship of humans, chimps, bonobos, and gorillas, use the term hominid to refer to all African hominoids. They then divide the hominid family into two subfamilies: the Paninae (chimps, bonobos, and gorillas) and the Homininae (humans and their ancestors). hominin The taxonomic subfamily or tribe within the primates that includes humans and our ancestors.

Name games: They reflect theoretical relationships among closely related species.

Though the DNA sequences of humans and African apes are 98 percent identical, the organization of DNA into chromosomes differs between humans and the other great apes. Bonobos and chimps, like gorillas and orangutans, have an extra pair of chromosomes compared to humans, in which two medium-sized chromosomes have fused together to form chromosome 2. (Chromosomes are numbered according to their size as they are viewed microscopically, so that chromosome 2 is the second largest of the human chromosomes. Recall Figure 2.4.) Of the other pairs, eighteen are virtually identical between humans and the African apes, whereas the remaining ones have been reshuffled.

Overall, the differences between humans and other African apes are not as great as the differences between gibbons (with twenty-two pairs of chromosomes) and siamangs (twenty-five pairs of chromosomes)—closely related species that, in captivity, have produced live hybrid offspring. Although some studies suggest a closer relationship between the two species in the genus Pan (chimps and bonobos) and humans than either has to gorillas, others disagree; the safest course at the moment is to regard all three genera—Pan, humans, and gorillas—as having an equal degree of relationship. (Chimps and bonobos are, of course, more closely related to each other than either is to gorillas or humans.)29

World History

World History