The archaeologist’s understanding of stratigraphy is the key to any involvement in criminal investigation. Archaeology is about identifying different layers of soil by virtue of their color, physical properties, or characteristics, and then interpreting what each individual layer means, thus developing a picture of what occurred in a given place over a period of time. Hence, if a hole has been dug in the ground the layers evident in section, suitably interpreted, can be used to provide a statement of what went on in that particular place over time. Furthermore, given that the individual layers are superimposed, there is a relative chronology present in that it is possible to determine which layer is the earliest in the sequence, which is the latest, and what the chronological order is for the layers in between. The same rules apply whether there are hundreds of layers, for example, as found in deep urban deposits, or just a few. In other words, the section also provides a ‘snapshot’ of events at the time the hole was dug. If a criminal then takes the opportunity to bury a victim in that location, then the ‘statement’ of what occurred and the ‘snapshot’ of the event in time are both altered. These are the features to which the forensic archaeology will need to be alert.

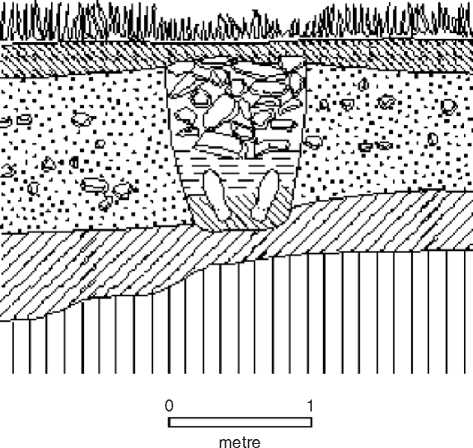

A victim buried in a grave is therefore contained within a stratigraphic environment (Figure 1). The grave is effectively a sealed deposit in which the

Figure 1 Stylized drawing of grave in profile. © 2008 Professor John Hunter. Published by Elsevier Inc. All rights reserved.

Individual and any evidence pertaining to that individual is sealed. Retaining the integrity of that environment is of great forensic importance since it contains evidence for the identity of the individual, the likely manner and cause of death, and the possible chronology of burial (according to the relative chronology of layers which are both earlier and later). In many scenarios human remains (usually bones) are discovered during building operations, drainage works, or garden cultivation. The remains are removed from the ground, taken away in order to be assessed as being either animal or human, and consequently both the ‘statement’ and the ‘snapshot’ are lost. The bones are effectively ‘stray’ and without context. If, alternatively, they are retained in position then the integrity of the grave can be preserved and important forensic issues of identification, cause and manner of death, and chronology can be given greater credibility. The first two of these are certainly unusual issues for the archaeologist to consider, but they are the key to the nature of forensic excavation and mark a significant point at which ‘traditional’ and forensic archaeology diverge.

Retaining the integrity of a burial can resolve in a very simple and effective way a range of likely situations. For example, this can involve the discovery of articulated remains during building or quarrying operations and an assessment of their stratigraphic position in relation to both the structure and other features, or the occurrence of disarticulated material either on the surface or in introduced deposits. In all instances it is a matter of preserving the integrity of any burial and of defining the context of any deposition. This can often enaBle a decision to be made as to whether the material is modern (and therefore of potential forensic interest) or ancient and therefore of only archaeological or historic interest. The search and recovery of human materials without awareness of contextual integrity may have the effect of dislocating any remains from their context or, more significantly from a forensic angle, of contaminating evidence with material which derives from earlier and/or later contexts. Any hint of contamination will almost certainly cast doubt in court over (1) the value of the evidence presented and (2) the professional expertise of the archaeologist concerned.

Retaining this integrity is the key to understanding what happened. In some instances where human remains have been found partly buried, the archaeologist will be needed to determine whether the remains were originally buried (i. e., as the result of actions by a third party) and have since been partly exposed or scavenged, or have become buried (i. e., by a process of natural soil accumulation, hillwash, etc.). In the former the matter will require criminal investigation, in the latter it may not. The distinction between the two will be negated if the primary investigation and recovery is not carried out archaeologically.

World History

World History