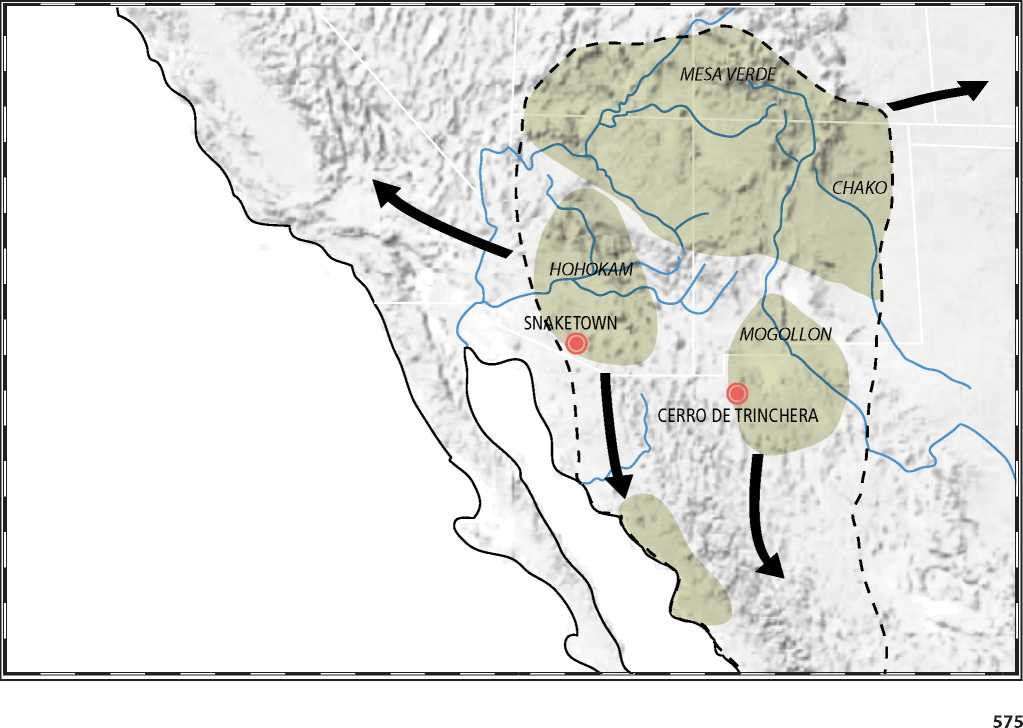

When one uses the word corn, or maize, one should not think of a single plant, but of the dozens of varieties that were produced with patience and experimental diligence over centuries in Guatemala and Mexico beginning around 2000 bce. By 800 bce, the Olmecs had made corn into a socio-religious world order. To bring the plant northward, not only out of the tropics, but also into a place where there is a shorter growing season was yet another test, but this too was overcome, around 300 ce in the southwest and 800 ce in the Mississippi area. In North America, corn was grown and developed in three different ecological zones: the arid Southwest, the forest world to the east of the Mississippi, and the prairie to the immediate west of the Mississippi. Each of these has a distinct history with the prairie corn growing cultures developing last, after 1300 ce, and largely because the other two were somewhat in decline (Figure 16.1).

Figure 16.1: Southwest emerging corn-centric cultures. Source: Florence Guiraud

Corn did not arrive alone. It came with new varieties of squashes and beans. The three plants came to be called the Three Sisters. Squashes had existed for some time in North America, but corn and beans were novelties. The three crops benefit from each other in a remarkable way. The maize plant provides a structure for the beans to climb, eliminating the need for poles. The beans in turn provide the nitrogen to the soil that the other plants utilize; and the squash, which spreads along the ground, blocks the sunlight, helping prevent establishment of weeds and yet keeping the soil moist. The three plants also complement each other when it comes to nutrition. Maize lacks the amino acids lysine and tryptophan, which the human body needs, but beans contain both; therefore, maize and beans together provide a balanced diet. Although the science was unknown until recently, the obvious health benefits of this arrangement were obvious, especially when augmented by a variety of meat, fish, berries, and nuts. The English and Spanish colonizers, when they arrived at the Americas, were uniformly struck, if not even perplexed, by the strong and healthy people they encountered.

The Three Sisters were not just an agricultural innovation, but a religious one was well. All corn-producing societies in the Americas soon incorporated the Corn Festival into their religious calendars. Taking place over a series of days and nights, it represented not only the renewal of the annual cycle, but also of the community’s social and spiritual life.1 First Society norms were not thrown out by the new religious formations. On the contrary, the new religious formations fused almost seamlessly into ancient traditions.

Figure 16.2: Cerro de Trincheras, Northwest Chihuahua, Mexico. Source: Bruce Thompson

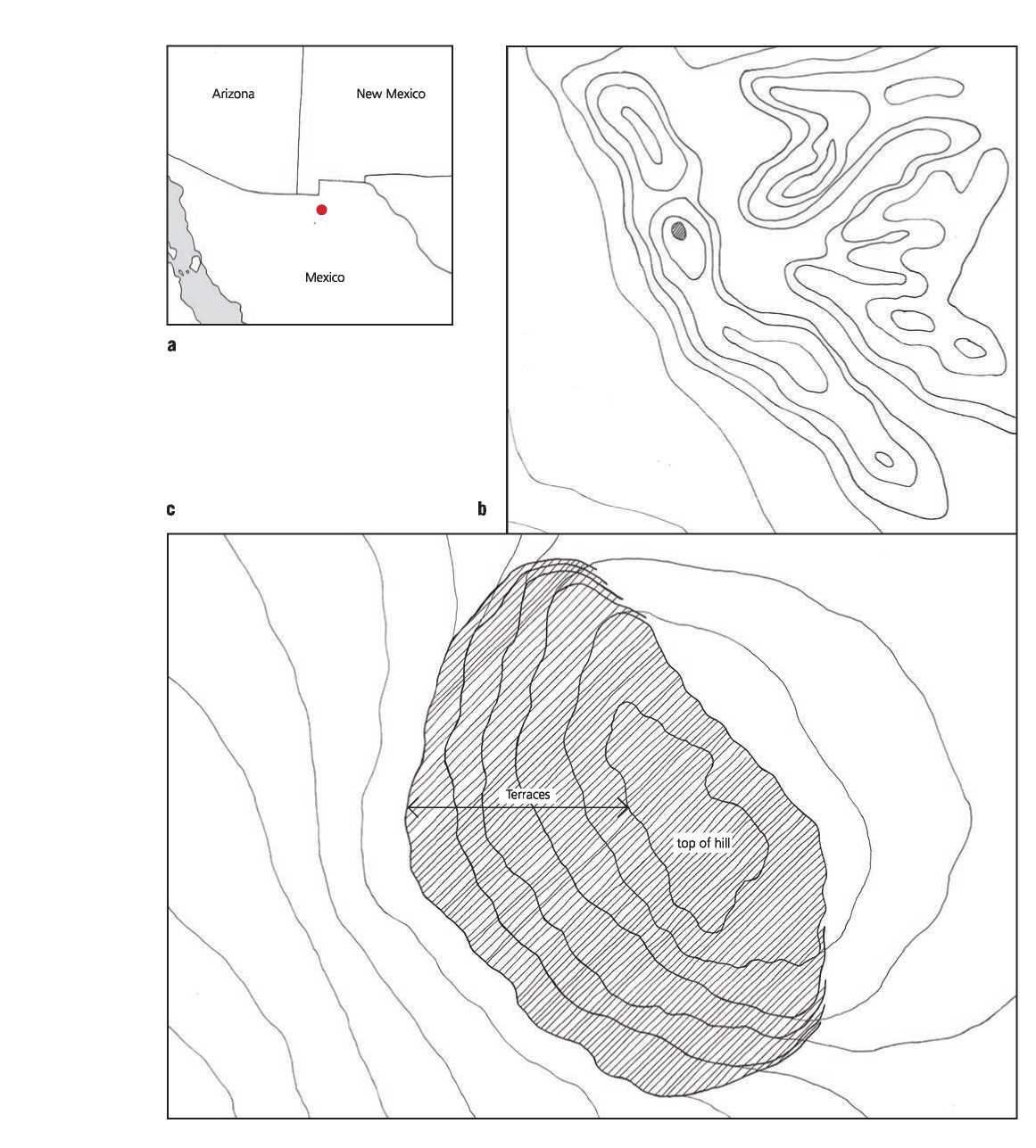

But the question is, How did this new agro-religious system relate to its Mexican origins? The answer is still clouded in uncertainty. Trade contact with Mexico is not in dispute, but in what context were the seeds brought northward to the Southwest? When corn first arrived about 1500 BCE, it was not yet considered a staple. Rather, it was incorporated into an existent plant-tending culture that stretched back thousands of years and that had nurtured local plants, many thought of as weeds today, such as amaranth and purslane. So who were these people who first produced terraces in northern Mexico? Cerro de Trincheras (“entrenched mountain”) was one of the earliest of almost 500 sites that have been found so far along the border between Mexico and the United States. The terraces, the remnants of which are still visible, would have required the movement of tons of earth and basalt cobbles. The riverside marshes below also served agricultural purposes. Though how the terraces were used is not yet known, it is quite likely that the farmers here perfected the transition of corn from a wetland crop to a dryland crop, setting the stage for the expansion of corn into the American Southwest (Figure 16.2). It is not accidental that the rise of this area into a corn-centric, chiefdom society coincided with the rise of the great Mexican city Teotihuacan, which by 150 ce had become the first, true metropolis of the Americas. The period between 250 and 650 then saw the flourishing of the Mayans in Guatemala and in the Yucatan; from 700 onward the Tolteks from their capital Tula (100 kilometers north-northwest of Mexico City) dominated the northern part of Mexico, establishing a prosperous turquoise trade route with the cultures in

The Southwest. Evidence of this trade is difficult to ascertain archaeologically, but in 1540 when Francisco Vasquez de Coronado first met the Anasazi at Zuni Pueblo, a trading party arrived, a member of which seems to have been a Plains Indian who told the Spaniards of a great river that almost certainly was the Mississippi, stimulating their interest in exploration eastward.2

Generally speaking, archaeologists difier-entiate, in these initial centuries, three difierent cultures in the Southwest, based on their difier-ent climactic conditions and the difierent cultural responses to corn: the Mongollon, the Ho-hokam, and the Anasazi. The Mongollon lived in high-altitude desert areas in what is today New Mexico and northern Mexico. The name comes from the mountain range that formed

Figure 16.3a, b, c: Cerro de Trincheras, Mexico: (a) map, (b) site plan, (c) plan.

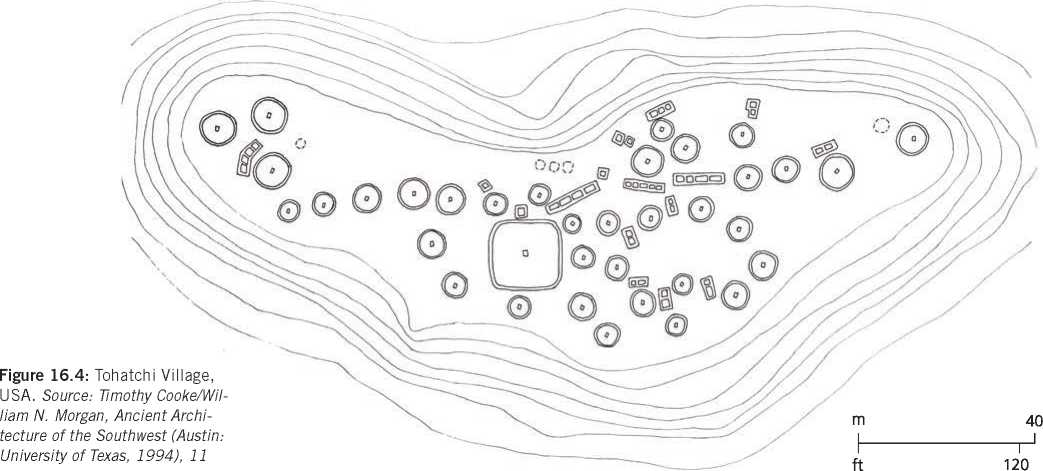

Their western border (Figure 16.3). Farming relied on rain in areas with good-quality soil.3 Early villages, from around 550 ce, were composed of just several pit houses. Some were almost round, others nearly rectangular. The larger ones probably served a communal purpose. We see increasing social differentiation taking place at Tohatchi Village, occupied from between 500 to 750 ce. Thirty-five or so pit houses are clustered around one large communal pit house. The rectangular structures are granaries (Figure 16.4).

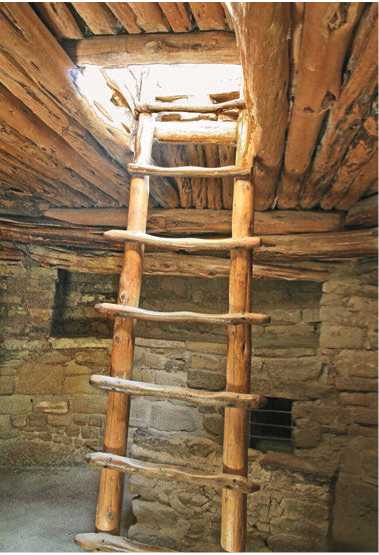

The Mongollon, despite the traditional informality of their social system, introduced what was to become a major element into the ritual consciousness of the Southwest tribes, the sunken communal house known as a kiva. They did not invent it, of course, since it goes back thousands of years and is an essential aspect of the pit house worldview. They did, however, make it into a space geared around their corn ceremony. In a sense they used the pit house to focus on this new, single plant. It was entered from the roof and had a bench around its perimeter wall. A fire pit was located in the center. Against one side, there was a type of altar exhibiting ritual objects including corn. In ceremonies, reserved for men, corn meal would be sprinkled around the kiva. Over time, the altar and its associated ceremonies would become increasingly elaborate and would remain the core element of Southwest cultures even when people no longer lived in pit houses themselves4 (Figure 16.5, Figure 16.6).

Figure 16.5: Bandelier kiva, Bandelier National Monument, New Mexico, USA. Source: Brian0918 (Public Domain)

Figure 16.6: Bandelier kiva, Mesa Verde National Park, Colorado, USA. Source: © Andreas F. Borchert (Http://creativecommons. org/licenses/by-sa/3.0/)

World History

World History