Throughout prehistory, the peopling of the Caribbean was due to multiple migrations from more than one place and by people of varying ethnic and linguistic affiliations. The earliest evidence of human occupation of the Caribbean, which dates to 5500 BC, comes from the Banwari Trace site in southwestern Trinidad. These people, who entered the Antilles from mainland South America, are known as the Ortoiroid culture. They practiced what archaeologists call an Archaic subsistence economy characterized by fishing and gathering. They manufactured and used groundstone, shell, and flaked stone tools, and lived in small mobile or semi-sedentary communities. By 2500 BC, the Ortoiroid had made their way through the Lesser Antilles, bypassing some islands (see Americas, Caribbean: The Lesser Antilles) to Puerto Rico.

At 4200 BC or thereabouts, Cuba was the first island of the Greater Antilles to be settled. The

Colonizers, who are known as the Casimiroid peoples, settled in Cuba and then migrated to Hispaniola. These first settlers probably came from Belize in Central America, since there are similarities between stone tools found there and in Cuba that date to this time period. A computer simulation that employed wind and water currents and other variables important to maritime travel suggests though that these people may have come directly from South America.

The Casimiroid people made tools that include large macroblades, core tools, scrapers, burins, and awls, anvils, and hammerstones. Their perishable technology, which likely constituted most of their material culture, has not been recovered. They lived in open-air sites and rock shelters and many of their sites appear to be workshops where they made stone tools. In Cuba, people occupied the coast and inland river valleys; rock shelter and open-air sites have been found in the Seboruco and Levisa River Valleys. The Levisa Rock Shelter (3190 BC) is one of the best studied sites from this time period. Sites on Hispaniola include the Vignier III site (3630 BC) in Haiti and the Barrera-Mordan (2610-2165 BC), Casimira, Honduras del Oeste, and Tavera sites in the Dominican Republic. The Maruca and Angostura sites in Puerto Rico indicate that the island was settled around 4000-5000 BC.

We know little about the subsistence practices of these people, other than they hunted terrestrial species such as hutias (a Capromyid rodent), iguanas, and snakes. Although the people also collected shellfish, it did not constitute a large part of the diet and there is no evidence for fishing. In Cuba, overpredation resulted in the extinction of the giant sloth. Sites dating to this time period or attributed to this culture have not been found in Jamaica, or the Bahamas.

By around 2000 BC to about 200 BC, the descendants of these people engaged in fishing, shellfish collecting, and plant gathering, and manufactured groundstone tools. Like their predecessors, they, too, lived in open-air sites and rock shelters. They probably also managed or tended fruit trees. Inter-island variation in material culture, settlement patterns, and dietary choices emerged. Such differences can be attributed to a combination of local cultural, environmental, and functional factors.

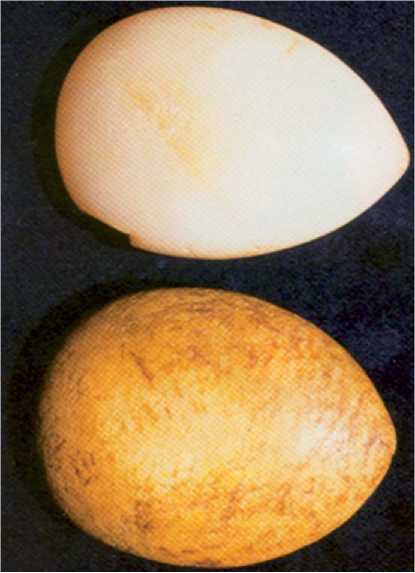

In Cuba, sites dating to this time period are located along the coast and in the interior. These people manufactured distinctive Strombus gigas shell artifacts, including gouges, cups, and hammers; ground-stone artifacts such as unique polished stone balls (spheroliths) and groundstone daggers, which served as burial accompaniments; polished ovoid stones, corazones, which have not been reported elsewhere in the Caribbean (Figure 2); stone rings, wooden objects, and pendants. They made blade tools, which

Figure 2 Heartstones (corazones). Cuba. Stone. 12.5 cm (white), 12.3 cm (yellow). Collection of the Montand Anthropological Museum, University of Havana. Photograph by Kristine Edle Olsen.

Were smaller and of poorer technical quality than those from the earlier period and flake tools eventually replaced them. Microlith tools have been found at a few sites. Complex, abstract, highly imaginative, geometric pictographs occur at the Punta del Este caves located on the Isla de la Juventud. Other important sites include Cayo Redondo and Cueva Funche (2050 BC); later occupations of the Levisa rockshelter, and burial sites from caves and open-air sites such as Cueva de El Purial (1110BC) and Canimar Abajo (2750BC). In western Cuba, people practicing an Archaic economy were not supplanted by later ceramic-making groups as they were elsewhere on the island; these communities persisted until the fifteenth century or later.

Sites in Haiti (2660 BC-AD 240) and the Dominican Republic (2030 BC-AD 145) are located in river valleys and coastal areas. Here the people hunted sloths, manatees, crocodiles, sea turtles, and whales, and collected shellfish. They made large stemmed spearheads, backed blades, and end scrapers, which they used to hunt these animals. It is believed that they are responsible for the local extinction of the sloth. They also made and used a wide array of groundstone tools including conical pestles, single - and double-bitted axes, rectangular hammer grinders, balls, hook-, fan-, and pegshaped objects, metates, mortars, incised bowls, and body adornments such as beads, and pendants. The people gathered or casually cultivated plants and fruit trees. Dried Zamia sp. leaves, Clusea rosea seeds, palm nuts, and maize pollen have been identified from sites in the Dominican Republic.

There is considerable regional diversity in the material culture from Puerto Rico during this time period and it resembles both Casimiroid and Ortoiroid cultural traditions. Some archaeologists have attributed this variation to the presence of culturally distinct peoples, differences in site function, or varying raw material properties and availability.

The people were mobile fisher-foragers who lived in small, open-air sites or rock shelters. A few larger communities may have been semi-sedentary. Settlements are located in coastal settings adjacent to mangrove swamps. The people engaged in low-level or casual root, seed, and tree crop cultivation and management. Food remains such as avocado and yellow sapote have been found at the Maria de la Cruz site. At Maruca and Puerto Ferro, starch grain analysis of groundstone artifacts has revealed evidence for domesticated maize, manioc, beans, sweet potato, and yautia (cocoyam). There is support from the Mai-sabel site that these people burned the landscape to create horticultural plots or regenerate natural areas with wild plants. Animal foods included shallow-water mollusks, marine fish, land crabs, and minor amounts of reptiles, turtles, and birds. The diet varied by locale. Terrestrial resources seem to have been favored at rock shelter sites such as Cueva Tembladera and Cueva Gemelos, while the occupants of coastal, open-air sites such as Maruca and Cayo Cofresi emphasized foods from marine or littoral sources.

The people manufactured flake tools and ground-stone tools that included small mortars, and conical manos, which are highly diagnostic of this time period. Use-modified stone tools include edge grinders, manos, and discoid nutting stones. At Maruca, some of the chert used to make the flaked stone tools has been sourced to Long Island (Antigua) (see Americas, Caribbean: The Lesser Antilles) and there is evidence from other sites of stone materials from other islands. The people also made tools from Strombus gigas such as celts, gouges, and picks that resembled those from Cuba. They also manufactured shell and bone points, net weights, and carved and drilled shell ornaments.

Sites in eastern Cuba [e. g., Caimanes III (AD 200), Belliza], eastern Dominican Republic [Punta Cana (340 BC-AD 830), Honduras del Oeste and el Barrio (230 BC-AD 420), and el Caimito (305 BC-AD 120)], and throughout Puerto Rico contain low densities of plain, small, low-fired ceramics that are globular and boat-shaped in form. Undecorated and decorated sherds (with incisions and punctation, mirroring designs found on stone bowls and wooden objects) have been found. It has been argued that people from the Middle Orinoco, coastal Columbia, or elsewhere in northern Latin America introduced pottery to these islands. Another argument claims that these people adopted ceramics from the Cedrosan Saladoid peoples who settled eastern Dominican Republic (see below). Some archaeologists propose that these people ‘borrowed’ and incorporated ceramic technology from neighboring societies or other areas in the cir-cum-Caribbean. It has also been suggested that ceramics evolved independently of external causes.

World History

World History