Cliff face is a remnant of the outer chamber; a roof fall in the inner chamber left a large chimney that opens in the hill above the cave.

Within a deposit some 25 m thick, Garrod’s excavations exposed six Paleolithic layers: basal Tayacian, layer G; Late Acheulean, layer F; Acheulo-Yabrudian, layer E; Lower Levalloiso-Mousterian, layers D and C; and Upper Leval-loiso-Mousterian, layer B (Garrod and Bate, 1937). Jelinek’s investigation, confined to a lo-meter-section corresponding to Garrod’s strata B-E and F, defined more than eighty-five geological beds in fourteen stratigraphic units. In following tire natural stratigraphy of tlie deposit rather than arbitrary horizontal levels, Jelinek and his colleagues were able to trace episodes of accumulation, nondeposition, and collapse of sediments into underlying solution cavities (Jelinek et al,1973).

In recovering more titan forty-four tltousand artifacts from the approximately 90 cu m of excavated sediment, Jelinek was able to trace in detail the artifact succession witliin the Tabun deposit. Within units XIV (Garrod’s layer G) and XIII-XI (Garrod’s layer E), he defined tlie Mugharan tradition, composed of three facies: Yabrudian, Acheulean, and Amudian. These are distinguished artifactually by relatively high frequencies of scrapers (Yabrudian), bifaces (Acheulean), and Upper Paleolithic elements, especially prismatic blades (Amudian). The Mugharan tradition shows a smooth transition into the overlying Levantine Mousterian horizon, as defined from upper unit Xl-unit I. Following Garrod’s initial cultural-stratigraphic partitions, the Levantine Mousterian succession consists of a D-type industry characterized by elongated Levallois points and blades; a G-type industry largely based on broad-oval Levallois flakes; and a B-type industry containing broad-based, “chapeau de gendarme, ” points.

Since Garrod’s initial research, evidence from the thick deposit at Tabun has been used for paleoclimadc reconstructions. Altliough the climatic implications of the classic Dama-Gazella curve developed by Garrod’s colleague, Dorothea M. A. Bate, has been largely discredited, it undoubtedly inspired subsequent work. Based primarily on the geostratigraphy and sediment analysis of tire cave’s deposit in conjunction with palynological results, Jelinek’s team traced a sequence of events tliought to correspond to the global temperature oscillations and attendant fluctuations in sea level that sttetched from oxygen isotope stages 56-3. Such a sequence suggests tliat the basal unit XIV was deposited within the last interglacial, some 120-130 years ago. [See Paleoenvironmental Reconstruction.]

Considerable controversy surrounds the absolute dating of Tabun, however. If accurate, the recent electron spin resonance (ESR) dates on teeth would push much of the sequence (layers D-G) back beyond interglacial times. Aside from substantial internal variability in the dates, they fail to fit the traditionally held chronology for Mediterranean marine transgressions, or that developed for micro vertebrates. Clearly, more dates are needed to resolve the problem.

In the initial excavation, Garrod recovered a partial skeleton of a female Neanderthal from either layer C or B, along with a damaged mandible of indeterminate taxonomic affinity from layer C. The presence of anatomically modern Homo sapiens remains from the nearby sites of Skhul and Qafzeh, in association witlr Mousterian industries similar to those at Tabun, suggests that the two hominid taxa may have been partially coeval within the Levant. The recent chronometry of the deposits even suggests that anatomically modern populations were indigenous to the region prior to a Neandertlial immigration from southeastern Europe some sixty thousand-ninety thousand years ago.

[5ee also Carmel Caves; and the biography of Garrod.]

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Garrod, Dorothy A. E., and Dorothea M. A. Bate. The Stone Age of Mount Carmel: Excavations at the Wady al-Mughara. Oxford, 1937. Initial report of the Tabun excavation, artifact, and faunal analyses. Jelinek, Arthur J., et al. “New Excavations at tlie Tabun Cave, Mount Carmel, Israel, 1967-1972: A Preliminary Report.” Paleoricnt 1.2 (1973): 151-183. Interim report on the findings of tlie new excavations, with sections on archaeology, geostratigraphy and sediments, and pollen.

Jelinek, Arthur J. “The Middle Paleolithic in the Soutiiern Levant from the Perspective of Tabun Gave.” In Prihisloire du Hvant: Chronologic et organisation de I’espace depute las origines jusqu’au Vie millcnaire, edited by Jacques Cauvin and Paul Sanlaville, pp. 265-280. Paris, 1981.

Jelinek, Artliur J, “The Tabun Cave and Paleolithic Man in the Levant.” Science 216 (1982): 1369-1375. Summarizes many of the results of the new excavations at Tabun, focusing on the correlations between trends in artifacts and paleoclimatic oscillations.

Jelinek, Arthur J. “The Amudian in the Context of tlie Mugharan Tradition at the Tabun Cave (Mount Carmel), Israel.” In The Emergence of Modern Humans, edited by Paul Mellars, pp. 81-90. Edinburgh, 1990.

Jelinek, Arthur J. “Problems in the Chronology of the Middle Paleolithic and the First Appearance of Early Modern Homo sapiens in Southwest Asia.” In The Evolution and Dispersal of Modern Humans in Asia, edited by Takeru Akazawa et al., pp. 253-275. Tokyo, 1992. Review of die chronometry of Middle Paleolithic deposits in the Levant. McCown, Theodore D., and Arthur Keith. The Stone Age of Mount Carmel, vol. 2, The Fossil Human Remains from the Levalloiso-Mousterian. Oxford, 1939. Original description of the fossil hominids recovered from Tabun and Skhul.

Donald O. Henry

TANNUR, KHIRBET ET-, Nabatean temple located in soutiiern Transjordan on a desolated summit, 704 m above sea level (map reference 2175 X 0421). The site overlooks Wadi el-Hasa, about 400 m below, soutlieast of the Dead Sea; it is close to the King’s Highway and is 7 km (4 mi.) nortli of anotiier temple, Kliirbet edh-Dharih, in

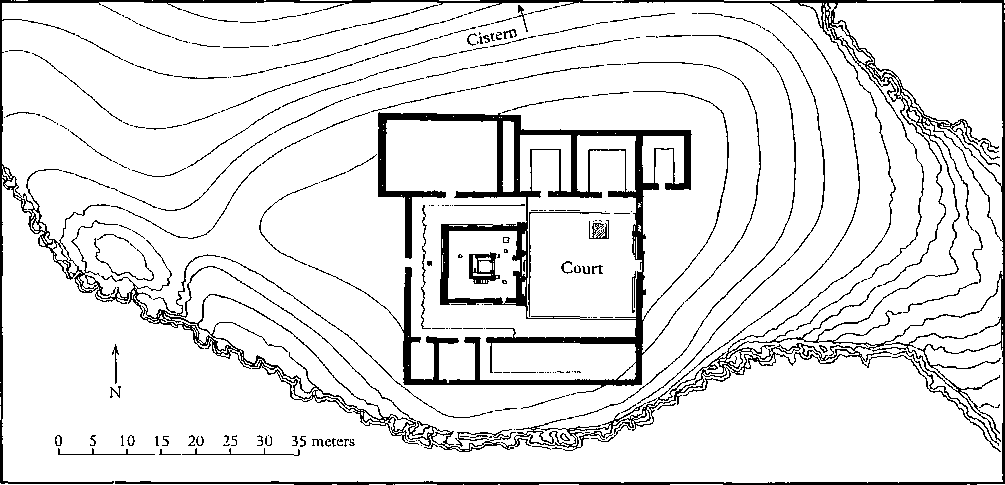

Wadi La'ban. Shortly after he carried out a preliminary survey there, Nelson Glueck directed an excavation in 1937 for the American Schools of Oriental Research and the Department of Antiquities of Transjordan. The architect Clarence S. Fisher drew its plan and reconstruction (see figure i). Most of the sculpture from the temple is exhibited in the Jordan Archaeological Museum and at the Cincinnati Art Museum. Since its excavation the site has been vandalized.

The temple (40 X 48 m) occupies all of the flat summit, accessed on tire east by a steep path. Its eastern facade was decorated with four engaged columns with Nabatean capitals. The eastern, or outer, court is almost square (15.68 X 15.47 nr) - The temple’s paved floor slopes to the southeast, where shallow channels open to the outside. An altar stood in the northeast corner, and porticoes on the nortlr and south sides, built on a two-step-high podium, opened onto one long triclinium on the south and to two square ones on tire north, with an additional one on the nortlrern exterior—all used for banquets by pilgrims. There are unspecified rooms on both sides on the western half of the paved court. There, a temenos, entered on the east via a monumental gate, is enclosed by walls decorated witlr four pilasters; a small door opened on the south. On the top of the walls Glueck reconstructed a series of busts of Greco-Roman divinities and of Nikes (Victories), and above the gate a semicircular relief of a vegetation goddess among leaves and fruit, topped by an eagle (Glueck, 1965). Inside tire temenos a square, monumental altar in the form of a small shrine (3.5 X 3.5 m in its last stage) was erected; its three phases give the temple’s relative chronological sequence (see below). Two small offering boxes containing burnt remains of sacrifices were hidden under the pavement in front of the altar.

There are no remains of the supposed earlier Edomite high place. Phase I consisted of a square construction (1.5 X 1.5 m and 1.75 m high) with Nabatean tooling on the outside; it was found filled with layers of ash and plaster. A low wall surrounded tire sacred space. Not long before phase II, a pavement was laid over a stepped surface that produced sherds of find Nabatean ware. The phase II altar was erected around the original one, but a false door decorated with friezes of rosettes and thunderbolts now adorned the east face; the two cult statues were placed inside this narrow space, according to the excavator’s reconstruction. A stairway springing from the north side led to the top of tlie monumental altar. During phase III, a new enclosing altar was built around the one from phase II; its pilasters were decorated on each side witli six busts of veiled goddesses emerging from a conchlike rosette; among tliem were a grain goddess and a fish goddess; vine and acantlius leaves decorated tlie doorjambs. A new staircase was added on the west side. The Russian doll structure of this monumental altar was probably the result of reconstructions after earthquake damage.

Glueck attributed the sanctuary to Hadad and his consort Atargatis on grounds of the iconography (symbols of power and fertility). Jean Starcky (1968), however, pointed outthat the only divine name found in the inscriptions was Qos, the Edomite god, and suggested a cultic relationship with the volcanic summit across Wadi el-Hasa. It may be that in the Nabatean period the old Edomite divinities were depicted

TANNUR, KHIRBET ET-. Figure I. Plan of the site. (Courtesy ASOR/Nelson Glueck Archive—Semitic Museum, Harvard University)

In the form of the popular divine couple of Hierapolis, Hadad and Atargatis. The sanctuary was an important pilgrimage center, as evidenced by several offering altars and incense burners, sherds of Nabatean cups, offering debris, as well as by the triclinia. [See Incense.]

According to Glueck, phase I lasted from about too bce to approximately 25 or to bce. He dated phase II by a Nabatean inscription to shordy before 7 bce and attributed to diis period most of die temple building, as well as a hypothetical temenos facade with Nabatean pilasters. He dated phase III to the first quarter of the second century ce, and attributed to it all of die decor on die temenos facade (Glueck, 1965). These dates have been contested. Michael Avi-Yonah assigned the sculptures from Tannur to the reign of Aretas IV (Avi-Yonah, 1981). Starcky, reexamining the dating of die temple and some of its reconstruction, attributed the entire building to phase II, at the turn of die century—except for die central altar shrine; he suggested the possibility of a cella ratiier than a central altar. Judith McKenzie attributed phase II to the end of die first century CE and distinguished a phase IIA. Fawzi Zayadine distinguished a Greco-Syrian and a Hellenistic-Parthian style that differs from McKenzie’s classification. The fine Nabatean sherds under the pavement of the temenos do suggest a period II date of the end of the first century, and thus a later chronology, phase I could be contemporary with the dated inscription (7 bce). Successive building programs probably lasted for decades, with some overlapping, and involved different workshops; consequentiy, stylistic variations should be used cautiously for dating. Sculpmres of similar styles to titat of Tannur are found at Khirbet edh-Dharih and at Petra. An earthquake destroyed the temple, probably in 363, and the site was abandoned. It was reoccupied by Byzantine squatters, probably looking for reusable materials.

[5ee also American Schools of Oriental Research; Hasa, Wadi el-; Nabateans; Temples, article on Syro-Palestihian Temples; and the biography of Fisher.]

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Avi-Yonah, Michael. “Oriental Art in Roman Palestine.” In Avi-Yon-ah's Art in Ancient Palestine: Selected Studies, pp. 119-211, pis. 2330. Jerusalem, 1981. Landmark study on Nabatean art, originally published in 1961, which develops tlie concept of “orientalizing” art. Glueck, Nelson. Deities and Dolphins: The Story of the Nabataeans. New York, 1965. Synthesis of Nabatean civilization focused on Khirbet et-Tannur; replaces the final report, altliough the preliminary reports provide useful additional information.

Glueck, Nelson. The Other Side of the Jordan. Rev. ed. Cambridge, Mass., 1970. General presentation of Glueck’s survey in Transjordan, witli a concise description of the temple of Khirbet et-Tannur. McKenzie, Judith. “The Development of Nabataean Sculpture at Petra and Khirbet Tannur.” Palestine Exploration Quarterly 120 (1988): 81-107, figs. 1-15. Recent work on Nabatean sculpture critiquing Glueck’s three phases of the temple building; based on a detailed stylistic analysis.

Starcky, Jean. “Le temple nabateen de Khirbet Tannur: A propos d’un

Livre recent.” Revtie Biblique 75 (1968): 206-235, pls. 15-20. Penetrating critique of Glueck’s Deities and Dolphins, challenging many of his conclusions.

Zayadine, Fawzi. “Sculpture in Ancient Jordan.” In The Art of Jordan: Treasures from an Ancient iMnd, edited by Piotr Bienkowski, pp. 5157. Liverpool, 1991. Includes a short classification of Khirbet ei-Tannur’s sculptural styles.

Marie-Jeanne Roche

TAURUS MOUNTAINS. A major mountain range running east-west along the southern coast of Turkey, the Taurus mountains integrate with and continue as tire Anti-Taurus in the eastern part of Turkey. The mountains were the arena for some of tire most important transformations in history, including plant and animal domestication. Wild forms of wheat and domesticable fauna are plentiful in the footirills even today. The Taurus Mountains are also air area in which innovative technology in metals took place. Long assumed to be the “silver mountains” of Hittite and Aldta-dian legends, the range abounds with extensive cedar forests and polymetallic ore deposits. This area is particularly ore rich because it is a tectonic zone of plate contact between the Arabian and Asian blocks. Silver, lead, copper, gold, iron, and tin are among some of the mineralizations witliin these mountains and are ascertained to have been mined as far back as the Chalcolitiric period. Native copper and malachite beads found at Aceramic Neolithic sites such as Ga-yonti and A§ildi also indicate tirat these minerals were recognized and exploited as far back as the eighth millennium BCE.

The mountains also provided the natural barrier through which major trade routes (and at times armies) passed from tite lowland agriculturally rich settlements. The Taurus highlands have abundant raw materials, some of which are lacking in tlie neighboring Levant and Mesopotamia. The earliest procurement of vital raw materials, such as flint, and decorative items, such as shells, pigments, and colored stones, began in the Paleolitliic period. Upper Paleolithic sites such as die Karain cave near Antalya in tire Taurus range have yielded stone tools from materials transported over great distances. A later (Neolititic and Chalcolithic periods, c. 7000-3000 bce), but similar, situation is evident with reciprocal exchange (i. e., barter), which dispersed obsidian, obtained in the volcanic zone just nortii of the Taurus, over long distances. In tite ensuing millennia, a highly complex form of trade established the early second-millennium bce Assyrian trading colonies. [5ee Assyrians.] In later periods a flow of goods connected Anatolian highland and lowland resource areas as well as neighboring regions.

Trade has often been singled out as an overriding cause of cultural change or social developments. In this view the evolution of complex, large-scale trading networks stimulated the growth of urban society. Areas lacking such raw materials as metal, timber, and building stones established methods of obtaining tltem. In time, this exchange became so large-scale, it necessitated an administrative organization to control the provisioning, production, and distribution of goods. Those in managerial positions thereby had access to a major source of wealth in the community and their power extended to other aspects of society. Whetlier trade was a prime mover or a consequence of developmental processes, it assuredly played a major role in the region of tlte Taurus Mountains.

K. Aslihan Yener and Hadi Ozbal (1986) have conducted several surveys in the central Taurus mountains in conjunction with a series of ore-sampling regimes for lead isotope analysis aimed at defining the social and economic organization of metal exchange in Southwestern Asia. The survey aimed to disclose broad regional and interregional patterns of trade and settlement. From 1983 to 1986, archaeological surveys located more than forty-one sites dating from the Paleolitlric through the Turkish Republican period (1925-). A majority of the sites are found on the summits of hills or terraced off tire slopes leading into the valley proper. Middle Paleolithic flint tools and implements of ground-stone, obsidian, and greenstone celts, which mark aceramic settlements, were found in the valley. In the flatter, intermontane valleys, large settlements were found on mound formations such as Porsuk, which dates to the second millennium bce and later.

Several important mines were located at Bolkardag, in a valley 15 km (9 mi.) long (approximately 40 l<m [25 mi.] from the strategic Cilician Gates) tltat passes through the Taurus mountains. The ores are polymetallic and a number of dikes are visible. Natural processes and mining activities have created many very irregular caves, cavities, and tunnels in the mountain range, some of which penetrate the mountain for up to 4 lun (2.5 mi.). The range is known as an important source of silver and goldj recent analyses taken from high-altitude veins also revealed high trace levels of tin in a galena-sphalerite ore. Because this form of tin was relatively rare, the more common form, cassiterite, was searched for in the Taurus area and located by the Turkish Geological Survey (MTA) near Camardi, 40 km (25 mi.) to the north, at Kestel mine.

The major evidence that Bolkardag ores were used from the Chalcolithic period through the Iron Age stems from lead isotope data. Isotope ratios of lead can be used to characterize sources and objects because lead ores differ from one another in their isotopic compositions from mining region to mining region. They are “fingerprints” with which to compare isotopic ratios derived from artifact samples. The Early Bronze Age correlations are especially informative. Silver jewelry from Troy and silver - and copper-based artifacts from Tell Selenkahiyeh, Hassek, Tell Leilan, and Mahmatiar in Syria and Anatolia are a few examples of crafts and sites using Taurus ores. [See Leilan, Tell] Late Bronze Age artifacts such as a silver stag from Mycenae,

Lead net sinkers from the Ka§-Uluburun shipwreck [YeeUlu-burun], and correlations to Cypriot lead indicate that maritime trade connected Bolkardag with coastal settlements. [See also (layonu; Goltepe; and Kestel.]

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Dixon, J. E., et al. “Obsidian and tlie Origins of Trade.” In Old World Archaeology: Foundations of Civilization, edited by Jeremy A. Sabloff and C. C. Lamberg-Kariovsky, pp. 80-88. San Francisco, 1972. Yener, K. Aslihan. “A Review of Interregional Exchange in Southwest Asia: The Neolithic Obsidian Network, the Assyrian Trading Colonies, and a Case for Third Millennium B. C. Trade.” Analolica 9 (1982); 33-75.

Yener, K. Aslihan. “The Producdon, Exchange, and Utilization of Silver and Lead Metals in Ancient Anatolia: A Source Identification Project.” AnatoKca 10 (1983): 1-15.

Yener, K. Aslihan. “The Archaeometry of Silver in Anatolia: The Bolkardag Mining District.” American Journal of Archaeology 90 (1986): 469-472.

Yener, K. Aslihan, and Hadi Ozbal. “The Bolkardag Mining District Survey of Silver and Lead Metals in Ancient Anatolia.” In Proceedings of the 24th International Archaeometry Symposium, edited by Jacqueline S. Olin and M. James Blackman, pp. 309-320. Washington, D. C., 1986.

K. Aslihan Yener

TAWILAN, site, primarily Iron II (Edomite), located just north of Petra, in the hills of southern Jordan (30°2o' N, 35°29' E; map reference 196 X 972). The ancient site, whose name is unknown, covers a terrace overlooldng the village of el-Ji, an intensely cultivated area close to ‘Ain Musa, a perennial spring. Several other Iron II sites have been discovered in the vicinity of Petra: Umm el-Biyara, Umm el-Ala, Ba'ja III, and Jebal al-Kser.

Survey and Excavation. Tawilan was surveyed in 1933 by Nelson Glueck, who concluded that between the tltir-teenth and sixth centuries bce it had been an important Edomite town. The site was excavated by Crystal Bennett from 1968 to 1970 and again in 1982, under the auspices of the British School of Archaeology in Jerusalem and tlien of the British Institute at Amman for Archaeology and History. Glueck had first identified tlie site with biblical Bozrah, the probable capital of Edom (“Explorations in Eastern Palestine and the Negeb,” Bulletin of the American Schools of Oriental Research 55 [1934]: 14). He subsequently agreed to the equation that modern Buseirah was Bozrah and alternatively proposed identifying Tawilan witli biblical Teman {Explorations in Eastern Palestine II, Annual of the American Schools of Oriental Research 15 [1935]: 83). Thirty years later, Roland de Vaux showed that the term Teman does not refer to a town but is to be equated with Edom or a part of Edom (“Teman, ville ou region d’Edom?” Revue Bihlique 76 [1969]: 379-385).

World History

World History