One global generalization that can be made with regard to most diseases is that wealth means health. The World Health Organization defines health as “a complete state of physical, psychological, and social well-being, not the mere absence of disease or infirmity.”247 While the international public health community works to improve health throughout the globe, heavily armed states, 15 World Health Organization. http://www. who. int/about/definition/en.

Medical pluralism The presence of multiple medical systems, each with its own practices and beliefs in a society.

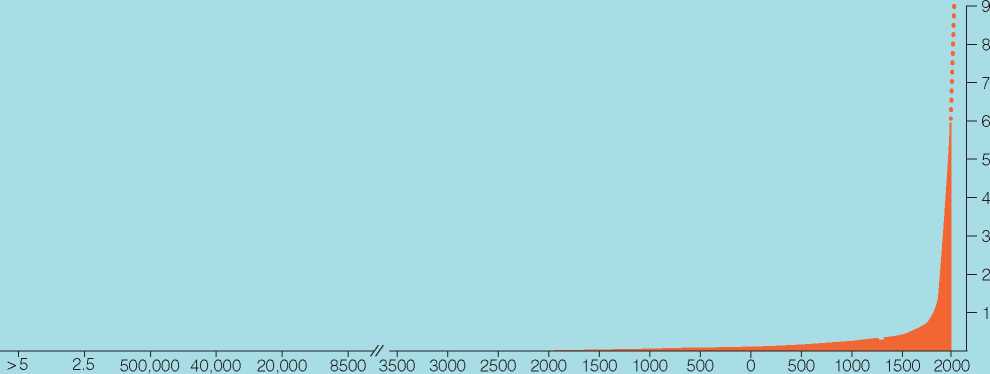

Billions of people

Million million

Year

Figure 13.5 Human population size grew at a relatively steady pace until the industrial revolution, when a geometric pattern of growth began. Since that time, human population size has been doubling at an alarming rate. The earth's natural resources will not be able to accommodate ever-increasing human population if the rates of consumption seen in Western industrialized nations, particularly in the United States, persist.

BCE

AD

Megacorporations, and very wealthy elites are using their powers to rearrange the emerging world system to their own competitive advantage. When such power relationships undermine the well-being of others, we may speak of structural violence—physical and/or psychological harm (including repression, environmental destruction, poverty, hunger, illness, and premature death) caused by exploitative and unjust social, political, and economic systems.

As we saw in Chapter 11, health disparities, or differences in the health status between the wealthy elite and the poor in stratified societies, are nothing new. Globalization has expanded and intensified structural violence, leading to enormous health disparities among individuals, communities, and even states. Medical anthropologists have examined how structural violence leads not only to unequal access to treatment but also to the likelihood of contracting disease through exposure to malnutrition, crowded conditions, and toxins.

At the time of the speciation events of early human evolutionary history, population size was relatively small compared to what it is today. With human population size at

Structural violence Physical and/or psychological harm (including repression, environmental destruction, poverty, hunger, illness, and premature death) caused by exploitative and unjust social, political, and economic systems.

Health disparity A difference in the health status between the wealthy elite and the poor in stratified societies.

Over 6.8 billion and still climbing, we are reaching the carrying capacity of the earth (Figure 13.5). India and China alone have well over 1 billion inhabitants each. And population growth is still rapid in South Asia, which is expected to become even more densely populated in the early 21st century. Population growth threatens to increase the scale of hunger, poverty, and pollution—and the many problems associated with these issues.

While human population growth must be curtailed, government-sponsored programs to do so have posed new health and ethical problems. For example, China’s much-publicized “one child” policy, introduced in 1979 to control its soaring population growth, led to sharp upward trends in sex-selective abortions, female infanticide, and female infant mortality due to abandonment and neglect. The resulting imbalance in China’s male and female populations is referred to as the “missing girl gap.” One study reports that China’s male-to-female sex ratio has become so distorted that 111 million men will not be able to find a wife. Government regulations softened slightly in the 1990s, when it became legal for rural couples to have a second child if their first was a girl—and if they paid a fee. Millions of rural couples have circumvented regulations by not registering births—resulting in millions of young people who do not “officially” exist.248

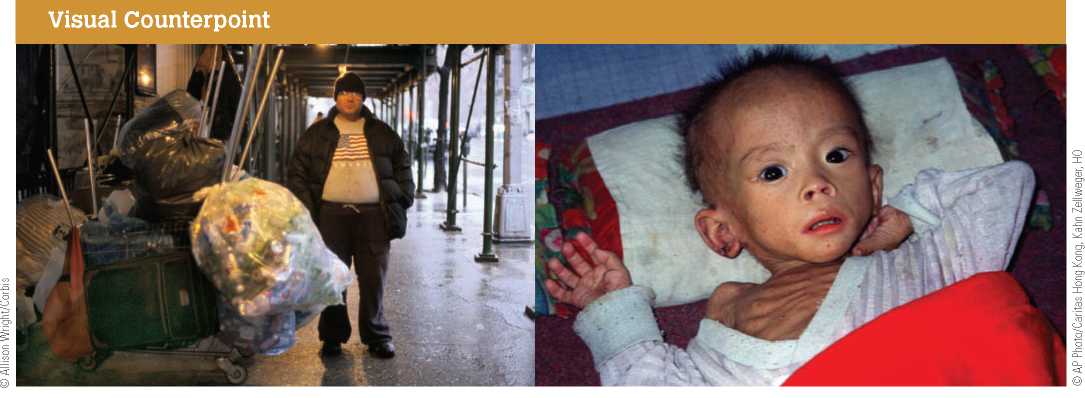

With an ever-expanding population, a shocking number of people worldwide face hunger on a regular basis, leading to a variety of health problems including premature death. It is no accident that poor countries and poorer citizens of wealthier countries are disproportionately malnourished. All told, about 1 billion people in the world are undernourished. Some 6 million children age 5 and under die every year due to hunger, and those who survive often suffer from physical and mental impairment.17

In wealthy industrialized countries a particular version of malnourishment—obesity—is becoming increasingly common. Obesity primarily affects poor working-class people who are no longer physically active at their work (because of increasing automation) and who cannot afford more expensive, healthy foods to stay fit. High sugar and fat content of mass-marketed foods and “super size” portions underlie this dramatic change. The risk of diabetes, heart disease, and stroke is also greatly increased in the presence of obesity. High rates of obesity among U. S. youth have led public health officials to project that the current generation of adults may be the first generation to outlive their children due to a cause other than war.

Environmental Impact and Health

Just as the disenfranchised experience a disproportionate share of famine and associated death, this same population also must contend with the lion’s share of contaminants and pollution. The industries of wealthier communities and states create the majority of the pollutants that are changing the earth today. Yet the impact of these pollutants is often felt most keenly by those who do not have the resources to consume, and thus pollute, at high rates.

For example, increasing emissions of greenhouse gases, as a consequence of deforestation and human industrial activity, have resulted in global warming. As the carbon emissions from the combustion of petroleum in wealthy nations warm the climate globally, the impact will be most severe for individuals in the tropics because these populations must contend with increases in deadly infectious diseases such as malaria. Annually it is estimated that 1.5 million to

2.7 million deaths worldwide are caused by malaria, making it the fifth largest infectious killer in the world. Children account for about 1 million of these deaths, and more than 80 percent of these cases are in tropical Africa. It is possible that over the next century, an average temperature increase of 3 degrees Celsius could result in 50 million to 80 million new malaria cases per year.18

Experts predict that global warming will lead to an expansion of the geographic ranges of tropical diseases and to an increase the incidence of respiratory diseases due to additional smog caused by warmer temperatures. As witnessed in the 15,000 deaths attributed to the 2003 heat wave in France, global warming may also increase the number of fatalities.19 To solve the problem of global

17 Hunger Project 2003; Swaminathan, M. S. (2000). Science in response to basic human needs. Science 287, 425; Historical atlas of the twentieth century. http://users. erols. com/mwhite28/20centry. htm.

18 Stone, R. (1995). If the mercury soars, so may health hazards. Science 267, 958.

19 World Meteorological Organization, quoted in “Increasing heat waves and other health hazards.” greenpeaceusa. org/climate/index. fpl/7096/ article/907.html.

The scientific definition of malnutrition includes undernutrition as well as excess consumption of foods, healthy or otherwise. Malnutrition leading to obesity is increasingly common among poor working-class people in industrialized countries. Starvation is more common in poor countries or in those that have been beset by years of political turmoil, as is evident in this emaciated North Korean child.

Warming, our species needs to evolve new cultural tools in order to anticipate environmental consequences that eventuate over decades. Regulating human population size globally and using the earth’s resources more conservatively are necessary to ensure our survival.

Global warming is merely one of a host of problems today that will ultimately have an impact on human gene pools. In view of the consequences for human biology of such seemingly benign innovations as dairying or farming (as discussed in Chapter 10), we may wonder about many recent practices—for example, the effects of increased exposure to radiation from use of x-rays, nuclear accidents, production of radioactive waste, ozone depletion (which increases human exposure to solar radiation), and the like.

Again the impact is often most severe for those who have not generated the pollutants in the first place. Take, for example, the flow of industrial and agricultural chemicals via air and water currents to Arctic regions. Icy temperatures allow these toxins to enter the food chain. As a result toxins generated in temperate climates end up in the bodies (and breast milk) of Arctic peoples who do not produce the toxins but who eat primarily foods that they hunt and fish.

In addition to exposure to radiation, humans also face increased exposure to other known mutagenic agents, including a wide variety of chemicals, such as pesticides. Despite repeated assurances about their safety, there have been tens of thousands of cases of poisonings in the United States alone and thousands of cases of cancer related to the manufacture and use of pesticides. The impact may be greater in so-called underdeveloped countries, where substances banned in the United States are routinely used.

Pesticides are responsible for millions of birds being killed each year (many of which would otherwise be happily gobbling down bugs and other pests), serious fish kills, and decimation of honey bees (bees are needed for the efficient pollination of many crops). In all, pesticides alone (not including other agricultural chemicals) are responsible for billions of dollars of environmental and public health damage in the United States each year.20 Anthropologists are documenting the effects on individuals, as described in the Biocultural Connection feature.

The shipping of pollutant waste between countries represents an example of structural violence. Individuals in the government or business sector of either nation may profit from these arrangements, creating another obstacle to addressing the problem. Similar issues may arise within countries, when authorities attempt to coerce ethnic minorities to accept disposal of toxic waste on their lands.

Hormone-disrupting chemicals are of particular concern because they interfere with the reproductive process. For example, in 1938 a synthetic estrogen known as DES (diethyl-stilbestrol) was developed and subsequently prescribed for 0 Pimentel, D. (1991). Response. Science 252, 358.

A variety of ailments ranging from acne to prostate cancer. Moreover, DES was routinely added to animal feed. It was not until 1971, however, that researchers realized that DES causes vaginal cancer in young women. Subsequent studies have shown that DES causes problems with the male reproductive system and can produce deformities of the female reproductive tract of individuals exposed to DES in utero. DES mimics the natural hormone, binding with appropriate receptors in and on cells, and thereby turns on biological activity associated with the hormone.249

DES is not alone in its effects: At least fifty-one chemicals—many of them in common use—are now known to disrupt hormones, and even this could be the tip of the iceberg. Some of these chemicals mimic hormones in the manner of DES, whereas others interfere with other parts of the endocrine system, such as thyroid and testosterone metabolism. Included are such supposedly benign and inert substances as plastics widely used in laboratories and chemicals added to polystyrene and polyvinyl chloride (PVCs) to make them more stable and less breakable. These plastics are widely used in plumbing, food processing, and food packaging.

Hormone-disrupting chemicals are also found in many detergents and personal care products, contraceptive creams, the giant jugs used to bottle drinking water, and plastic linings in cans. About 85 percent of food cans in the United States are so lined. Similarly, the harmful health consequences of the release of compounds from plastic wrap and plastic containers during microwaving are now known, though for many years using plastic in the microwave was an acceptable cultural practice. Similarly, bisphenol-A (BPA)—a chemical widely used in water bottles and baby bottles (hard plastics)—has recently been associated with higher rates of chronic diseases such as heart disease and diabetes, and it has been shown to disrupt a variety of other reproductive and metabolic processes. Infants and fetuses are at the greatest risk from exposure to BPA.

While there is consensus in the scientific community and governments are starting to take action (the Canadian government declared BPA a toxic compound), removing this compound from the food industry may be easier that ridding the environment of this contaminant. For decades billions of pounds of BPA have been produced each year, and in turn it has been dumped into landfills and bodies of water. As with the Neolithic revolution and the development of civilization, each invention creates new challenges for humans.

The implications of all these developments are sobering. We know that pathologies result from extremely low levels of exposure to harmful chemicals. Yet, besides those used domestically, the United States exports millions of pounds of these chemicals to the rest of the world.250

Biocultural Connection

The toxic effects of pesticides have long been known. After all, these compounds are designed to kill bugs. However, documenting the toxic effects of pesticides on humans has been more difficult, as they are subtle—sometimes taking years to become apparent.

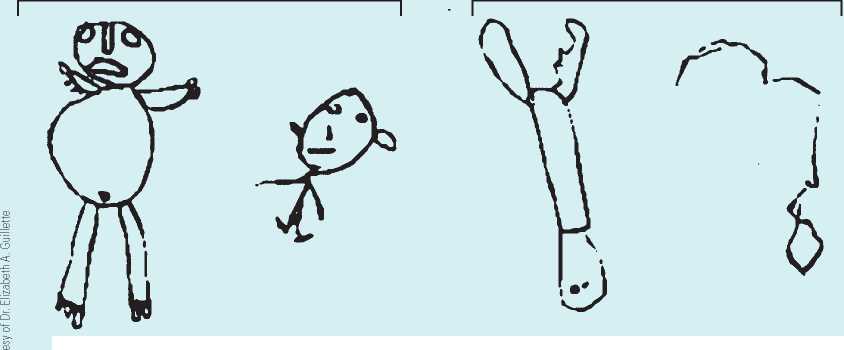

Anthropologist Elizabeth Guillette, working in a Yaqui Indian community in Mexico, combined ethnographic observation, biological monitoring of pesticide levels in the blood, and neurobehavioral testing to document the impairment of child development by pesticides.® Working with colleagues from the

Technological Institute of Sonora in Obregon, Mexico, Guillette compared children and families from two Yaqui communities: one living in farm valleys who were exposed to large doses of pesticides and one living in ranching villages in the foothills nearby.

Guillette documented the frequency of pesticide use among the farming Yaqui to be forty-five times per crop cycle with two crop cycles per year. In the farming valleys she also noted that families tended to use household bug sprays on a daily basis, thus increasing their exposure to toxic pesticides. In the foothill ranches, she found that the only pesticides that the Yaqui were exposed to consisted of DDT sprayed by the government to control malaria. In these communities, indoor bugs were swatted or tolerated.

Pesticide exposure was linked to child health and development through two sets of measures. First, levels of pesticides in the blood of valley children at birth and throughout their childhood were examined and found to be far higher than in the children from the foothills. Further, the presence of pesticides in breast milk of nursing mothers from the valley farms was also documented. Second, children from the two communities were asked to perform a variety of normal childhood activities, such as jumping, memory games, playing catch, and drawing pictures.

The children exposed to high doses of pesticides had significantly less stamina, eye-hand coordination, large motor coordination, and drawing ability compared to the Yaqui children from the foothills. These children exhibited no overt symptoms of pesticide poisoning— instead exhibiting delays and impairment in their neurobehavioral abilities that may be irreversible.

Though Guillette's study was thoroughly embedded in one ethnographic community, she emphasizes that the exposure to pesticides among the Yaqui farmers is typical of agricultural communities globally and has significance for changing human practices regarding the use of pesticides everywhere.

BIOCULTURAL QUESTION

Given the documented developmental damage these pesticides have inflicted on children, should their sale and use be regulated globally? Are there potentially damaging toxins in use in your community?

® Guillette, E. A., et al. (1998, June). An anthropological approach to the evaluation of preschool children exposed to pesticides in Mexico. Environmental Health Perspectives 106, 347.

Foothills

Valley

60-month-old

Female

71-month-old

Male

71-month-old

Female

71-month-old

Male

Compare the drawings typically done by Yaqui children heavily exposed to pesticides (valley) to those made by Yaqui children living in nearby areas who were relatively unexposed (foothills).

Human Sperm Concentration

50%

44%

28%

21%

16%

1930-51 1951-60 1961-70 1971-80 1981-90

Figure 13.6 A documented decline in human sperm counts worldwide may be related to widespread exposure to hormone-disrupting chemicals.

Hormone disruptions may be at least partially responsible for certain trends that have recently concerned scientists. These range from increasingly early onset of puberty in human females to dramatic declines in human sperm counts. With respect to the latter, some sixty-one separate studies confirm that sperm counts have dropped almost 50 percent from 1938 to 1990 (Figure 13.6). Most of these studies were carried out in the United States and Europe, but some from Africa, Asia, and South America show that this is a worldwide phenomenon.

World History

World History