Know, first, who you are; and then adorn yourself accordingly. —Epictetus

While it could be argued that artifacts used to adorn the body go beyond what is absolutely necessary for survival, in some ways many objects used for ornamentation are as important to the body as clothing itself (Burton 2001:27). Adornments temporarily transform the body (Steiner 1990). Consider how leaders and chiefs often don their best regalia for political events and include adornments such as presidential medals to publicly display their knowledge and authority to their audience. These adornments are integral to the sartorial presentation of the self and are difficult to identify as a separate category.

Adornment is also used to add to the body to create meaning, and it is often the case that items of adornment had different meanings for their users than they did for their producers. For example, the archaeological work on glass beads recovered from the Spanish colonial communities of St. Augustine and Pensacola has suggested that beads were used not only as jewelry but also for rosaries and particularly (in certain contexts) as amulets and magical protection for women (Deagan 2002). These uses point to people’s active manipulation of adornment and to how the meaning of adornments is contingent on context. The objects of adornment under consideration in this chapter are glass beads, crucifixes, and pierced coins.

Examples of colonial adornments derive from European, African, Native American, and multiethnic contexts. Whether they were secular or sacred, adornment practices were an important visual constituent of colonial identity. Although objects of adornment are not exactly numerous at all colonial sites, they are often recovered from sites throughout North America. They

Include items such as jewelry, beads, hair combs, and religious medals. For example, at the Stobo Plantation site in South Carolina, adornment artifacts represent a very small percentage of the assemblage (just over 1 percent) (Zierdan 2002:192-194). But the adornment artifacts that were recovered from this eighteenth-century rice plantation are notable. A silver cane tip indicated that when James Stobo presented himself in the community he did so with style (Zierdan 2002:192). Yet a brass finger ring set with a glass stone engraved with a crucifix did not belong to Stobo, a strident dissident who deplored the Catholic Church, and researchers of the site were left to wonder who could have deposited this ring. Could it have been owned by enslaved Africans living on the plantation who were devout Catholics, or was it owned by Christianized Indians from the Apalachee province? As Zierden suggests (2002:195), although we may never know the provenance of this object, the object is important as a signature of colonialism, the meeting of diverse cultural beliefs and ideologies. This ring is also emblematic of the practices of dress during the colonial period. Colonial peoples in North America built upon familiar adornment practices but combined objects of adornment on the body in ways that were unique to the context of colonial America.

Capturing the Sky: Nueva Cadiz Glass Beads

Glass beads first arrived in North America from production sites in Italy and Amsterdam and other areas of Europe and were some of the first items to be traded with the indigenous peoples. They soon became one of the most common European-manufactured items related to clothing and adornment in North America and other parts of the globe during the colonial period. Glass beads were produced in a multitude of colors and forms that included very small beads (sometimes described as seed beads), very large beads made of blown glass; beads wound with wire; drawn, pressed and molded beads; and etched beads. They were produced in almost every conceivable color or color combination.

As a commodity and an item with meaning, glass beads have reached almost an iconic status within material studies in historical archaeology. Quimby (1966) detailed the occurrence of glass beads on early colonial-period sites throughout the Great Lakes. Kidd and Kidd’s (1970) typology of glass beads brought new understandings of the construction and composition of beads to archaeological analysis, while Karklins (1985, 1992), Hamell (1983), Phillips (1998), and Turgeon (2001, 2004) discuss the use and meaning of glass beads for Native peoples in Canada and the Eastern Woodlands. This research on the chronology and sourcing of glass beads has provided a solid baseline for current discussions of the use and meaning of glass beads in Native American contexts, particularly for the current emphasis on the use of different bead forms. Color has also been an important component of this research on Native American contexts (see especially Hamell 1983) and has also been a central concept in discussions of glass beads recovered from African American sites (Singleton 2005; Thomas 2002; Wilkie 1995,

1997).

Recent scholarly interest has focused on how Native peoples incorporated glass beads into adornment and embroidery practices throughout the colonial Eastern Woodlands and on the complex meanings glass beads carried in those contexts (e. g., Karklins 1985, 1992; Phillips 1998; Turgeon 2001, 2004, 2006). Laurier Turgeon eloquently argues that material culture placed on the body becomes part of one’s body:

Food and clothing are integrated into or put onto the body and thereby transform it. . . . A piece of clothing is more than a sign, or a representation of something, it is an essence in itself. This material association between biological (the body) and cultural domains is what makes alimentary and vestimentary practices so efficient for the affirmation of individual and collective identities (Turgeon 2006:108).

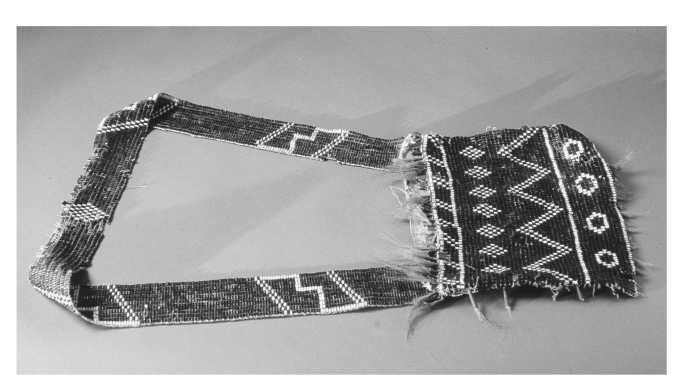

Turgeon (2004:35-36) has argued that glass beads were a particularly important aspect of colonial dress because of the associations between beads and bodies, particularly because beads were often associated with eyes or light. Thus, when an individual wore beads on the body, they were an important visual aspect of how that person constructed his or her identity. Light is captured in glass and this translucence was unique among much colonial-period material culture. As Turgeon (2004:35) reminds us, “The polished surface of beads conveyed the notions of finish, brilliance, alive-ness, and action.” In many northeastern Native American communities during the early colonial period, glass beads were metaphors for vision and visibility (Turgeon 2004:36). Among many Native American communities, glass beads were initially worn as jewelry, but soon they were incorporated into other items, such as the bag seen in Figure 4.1.

In the archaeological record, we rarely have a complete beaded object to use as the basis for a discussion of beading practices. Usually glass beads

4.1. Shot bag of glass beads with tinklers, eighteenth century, Quebec. Courtesy of President and Fellows of Harvard College, Peabody Museum of Archaeology and Ethnology, 67-10-10/288.

Are recovered as single objects, and interpretations tend to focus on analysis based on chronology. Archaeological research that examines how glass beads were used in practices of clothing and adornment based on where beads are located in relation to human remains has also provided some detail (e. g., Loren 2007a). Additionally, ethnographic collections provide numerous examples of how glass beads were sewn onto clothing, woven into belts, embroidered on bags, worn as necklaces and earrings, woven into hair, and hung from cradle boards (Karklins 1992:12-13; Neitzel 1965:88-89; Pietak 1998). One example of this use of glass beads is the eighteenth-century bag manufactured in Quebec shown in Figure 4.1. At first glance, the bag appears to be made from wampum. A closer examination, however, reveals that the bag is constructed using cut dark ultramarine and white glass beads woven in a geometric design commonly used in wampum belts. The back of the bag is composed of blue stroud with metal tinklers sewn along the edges. The ingenuity used to create this object suggests more than simply exchanging one material for another. The glass beads on this item, while mimicking wampum, have a translucence and luster not found in shell beads, indicating that the raw material itself had value to the beader that shell beads did not.

With these concepts in mind, I want to focus on a specific type of glass bead found on seventeenth-century colonial sites in North America: the

Nueva Cadiz bead. Nueva Cadiz is the modern name for a particular type of tubular drawn-glass bead produced during the sixteenth century; it was identified by John Goggin (Deagan 2002:12, 57). These beads, which were made of both turquoise and darker blue glass, were produced in two forms: straight and twisted. Because of the limited period of production, Nueva Cadiz beads are extremely diagnostic and are used to date early colonial-period sites in North and South America. A variety of Nueva Cadiz beads that were shorter and smaller than those usually defined as Nueva Cadiz were produced in the late sixteenth and early seventeenth centuries, indicating a brief renaissance of this bead type (Lapham 2001). Nueva Cadiz and Nueva Cadiz-like beads have been mostly commonly associated with Spanish colonial sites. However, these beads have been recovered from other colonial contexts, including Seneca sites in New York, Susquehan-nock sites in Pennsylvania, Iroquois sites in southern Ontario, and Native American contexts in Wisconsin. (Ellis and Ferris 1990; Fitzgerald 1982; Kent 1983; Kenyon 1982; Lapham 2001; Smith and Graybill 1977; Sempow-ski 1994; Wray 1983; Wray et al. 1991). The string of glass beads shown in Figure 4.2 was recovered from a Native American site in Wisconsin.

The majority of sites mentioned here are Native American contexts, yet Lapham (2001) discusses an assemblage of Nueva Cadiz-like beads recovered from the early English colony of Jamestown. Established in 1607, Jamestown was located on the banks of the James River 60 miles from the mouth of the Chesapeake Bay and approximately 15 miles from the Powhatan community of Werowocomoco, which was the center of the Powhatan Confederacy (Gallivan 2003, 2004). Beginning in 1994, a major archaeological program known as the Jamestown Rediscovery Archaeology Project has worked to recover much of the early fort, the remains of several houses and wells, the graves of several of the early settlers, and thousands of early seventeenth-century artifacts (Kelso et al. 1997, 1999; Mallios 2000). During the early years of the Jamestown settlement, the Powhatan Confederacy—a polity of 30 Native American communities—was led by Chief Powhatan (Wahunsunacock), an individual who was documented in both historical and popular sources (Gallivan 2003, 2004). The site of Werowocomoco was first located by archaeological survey in the 1970s. Archaeological investigations at the site and collaborative research on the Powhatan Confederacy are conducted by the Werowocomoco Research Group (Gallivan 2003, 2004; Gallivan et al. 2006).

4.2. Conical copper beads and Nueva Cadiz glass beads, seventeenth century, Wisconsin. Museum documentation indicates that beads are “as originally strung." Courtesy of President and Fellows of Harvard College, Peabody Museum of Archaeology and Ethnology, 21-15-10/92461.

Lapham (2001) notes that the Nueva Cadiz-like beads recovered from Jamestown are a later variety of Nueva Cadiz beads that were produced in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries. At 18 percent of the total bead assemblage at the site, this type of bead occurs in much greater quantities at Jamestown than any at other site in the Middle Atlantic and northeastern regions. The Nueva Cadiz-like turquoise beads recovered from Jamestown are smaller than those recovered from other contemporaneous sites. Additionally, a navy blue variety recovered at the site appears to be unique

To Jamestown Island. Lapham (2001:5) indicates that “differences between Nueva Cadiz-like beads unearthed at Jamestown and those found elsewhere in the Middle Atlantic and Northeast attest to the uniqueness of the two Jamestown varieties and to their affinity with 16th-century Spanish types.”

Lapham’s research focuses on assessing the origin of and chronology for the beads recovered from Jamestown. But how were these beads used at Jamestown? Should we assume that the Nueva Cadiz-like beads recovered from the site were used only for trade with Powhatans living in the neighboring community of Werowocomoco? Gallivan and colleagues (2006:33) note that socioeconomic relations between Jamestown and Werowocomoco were established through the exchange of “food for items with symbolic resonance (including copper and glass beads) and those with practical uses (including swords and iron tools).” John Smith, perhaps one of the most well-known English visitors at Werowocomoco, was known to have traded numerous blue glass beads to Powhatan individuals, and these glass beads were fit into aspects of Powhatan color symbolism (Gallivan et al. 2006:34). In The generall historic of Virginia, John Smith provided this account of an exchange with Chief Powhatan:

[Smith] glanced in the eyes of Powhatan many trifles, who fixed his humor upon a few blew beades. A long time he importunately desired them, but Smith seemed so much the more to affect them, as being composed of a most rare substance of the coulour of the skyes, and not to be worne but by the greatest kings in the world. This made him halfe madde to be the owner of such strange Jewells: so that ere we departed, for a pound or two of blew beades, he brought over my king for 2 or 300 Bushells of corne; yet parted good friends (Smith 1624:108).

Presumably, the Nueva Cadiz-like beads recovered from Jamestown were to be used not in the dressing practices of English colonists but rather for trade with local Powhatans. Hundreds of round blue glass beads have been recovered from both Jamestown and Werowocomoco, yet no Nueva Cadiz or Nueva Cadiz-like beads have been recovered from Werowoco-moco (Gallivan et al. 2006). What accounts for this? It may be that Powhatans were just not interested in the shape of Nueva Cadiz beads and chose round glass beads over this tubular variety. This explanation would account for the fact that tubular glass beads have been recovered at Jamestown. But it is possible that Nueva Cadiz-like beads were worn by members of the Jamestown community?

Francis (1988:2, 30-31) and Turgeon (2004:27) argue that Europeans placed little economic value on beads, desiring instead gems and gold and silver jewelry. This sentiment is captured in the 1624 quote above, where Smith calls glass beads “trinkets.” Such historical quotes ground the reasoning of Francis, Turgeon, and others that glass beads were rarely worn by people of European descent in North America and that they were highly valued and used only by people of African and Native American descent. People of European descent did wear and use glass beads, but most forms recognized by scholars as those worn and used in North America are jet (for rosaries), crystal, and small cut-glass beads used for embroidery on clothing and altar cloths (Deagan 2002:38-40; White 2005:81-83; Malis-chke 2009:32-34). Glass beads outside of these categories are usually associated with non-European people in different colonial contexts.

These kinds of interpretations, however, narrow the range of interpretive possibilities for the use of glass beads as adornment. We know that some glass beads (including varieties that are assumed to be “made for trade”) were incorporated into larger pieces of jewelry and were even worn as necklaces by European women of modest means, such as servants, chambermaids, and valets who could not afford more expensive forms of jewelry (Turgeon 2004:27; see also White 2005:81-83). With this information in mind, is it so difficult to imagine that in the struggling community of seventeenth-century Jamestown (and even with John Smith’s judgment of glass beads as “trifles”), those wishing to decorate their bodies would follow the lead of their Powhatan neighbors and include glass beads as part of their practices of adornment? And that this practice may have occurred in other colonial regions where people of European descent emulated Native and African neighbors to wear glass beads as adornment and, in so doing, actively created new identities in colonial North America?

Attaching Christ: Crucifixes and Other Religious Adornments

Perhaps there is no more powerful emblem of conversion to Christianity than the crucifix. The crucifix depicts Christ’s body at the moment of death. Worn on the body, this image symbolizes the metaphorical submission of self (both the physical body and the soul) to God. Deagan (2002: 38) notes that when used in a Catholic context, crucifixes and other religious items “are not considered to be charms, amulets or idols but rather are tangible reminders to Catholics of their faith, religious duties, and rewards.” During the period when Christian missionaries were attempting to convert souls in the New World, especially during the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, they distributed crucifixes and other religious paraphernalia among Native American populations to allow individuals to visually denote their conversion as an attachment on the body. Native peoples in the Americas resisted attempts to convert them in varying degrees, depending on the group being converted and those attempting the conversion. Nevertheless, crucifixes and other religious ornaments are common at many seventeenth - and eighteenth-century sites, particularly mission contexts.

During the seventeenth century, numerous places of worship and conversion were established in the American colonies, including several praying towns in New England and numerous Catholic missions in New France, New Amsterdam, and New Spain. The first missions in present-day New Mexico (then part of New Spain) were established after 1598. During the next 100 years, Franciscan priests founded more than 40 additional missions, most of them along the Rio Grande (Weber 1994:94-97; see also Lightfoot 2004). Among these was the seventeenth-century mission established among the Hopi at Awatovi.

One of the more interesting contexts relating to the incorporation of religious symbols into the lives of Native peoples are those that were recovered by archaeologists at the site of the Pueblo Revolt (Pruecel 2002). In 1680, following 82 years of colonization, the Pueblo Indians of New Mexico rose up against the Spanish Crown and its arm of oppression—the Church. During the Pueblo Revolt, 401 Spanish colonists and 21 Franciscan missionaries were killed (Pruecel 2002; Wilcox 2002). Following the revolt, Pueblo peoples were able to revitalize their traditional religion. They “revived their traditional ceremonies, rebuilt their kivas, and reconsecrated their shrines” (Pruecel 2002:3). For Pueblo people, the crucifix was the mark of Spanish oppression (Figure 4.3). The archaeological record shows that they reinterpreted crosses and crucifixes and incorporated them into kiva art and ceramics. They also included them in several burials.

Mobley-Tanaka (2002) argues that during the period of Spanish colonization prior to the Pueblo Revolt, Pueblo artists incorporated crosses into their ceramics, jewelry, and mural paintings not as a mark of religious conversion but rather as a symbol intended to misinform Spanish viewers. During the period of Spanish colonization prior to the revolt, the cross

4.3. Part of Jeddito black-on-yellow pottery bowl, Awatovi, Antelope Mesa, Arizona, ca. 1629-1700. Courtesy of President and Fellows of Harvard College, Peabody Museum of Archaeology and Ethnology, 35-126-10/5560A.

Replaced a stylistically similar mark for dragonflies and birds in flight that existed on Pueblo pottery prior to colonization; the similarity of these two symbols made it possible for the Pueblo peoples to silently infuse meaningful images into Spanish-controlled places. Liebmann (2002) provides evidence that Pueblo artists continued to incorporate and transform Christian imagery into their discourse of resistance as they formulated their identities following the Pueblo Revolt. In his analysis of a drawing located on the wall of a Pueblo village occupied during or just after the revolt or reconquest, Liebmann discusses how Pueblos resisted Spanish colonization through the inversion of Spanish images. An image on the wall depicts a figure with a halo that strongly resembles European depictions of the Virgin Mary, saints, and the Holy Trinity. Other aspects of the image—the points in the halo and two concentric circles surrounding the face—also suggest the incorporation of traditional Pueblo art. The image is thus a combination of Christian and Pueblo imagery and is indicative of strategies used to preserve culture and recreate Pueblo identities; it allowed for active, explicit resistance rather than the passive forms of resistance found in the use of crosses prior to the revolt (Liebmann 2002).

A similar strategy of identity manipulation is discussed by Elizabeth Bollwerk (2006), who offers an interesting example of how Native peoples

Strategically used Christian symbols during the nineteenth century. Boll-werk outlines how Potawatomi chief Leopold Pokagon employed a form of “selective consumerism” in his Michigan village during the early part of the nineteenth century that enabled him to control the types of European-manufactured goods that were entering his community (see also Wagner 1998). Chief Pokagon and Pokagon band members allied themselves with Catholic missionaries rather than with the Baptist ministers who lived nearby. They did this only for religious reasons but also because it created an important political alliance during the band’s struggle to avoid removal from tribal homelands. In 1830, Pokagon and other band members were baptized by the vicar general of the Detroit Diocese, and soon after a mission was established to serve the Pokagon Potawatomi. This affiliation with the Catholic Church created a new identity for the Potawatomi of the St. Joseph River Valley; thereafter they were known as the Pokagon Band of Potawatomi Indians (Bollwerk 2006). The St. Benedict medal recovered from the Pokagon Village site (20BE13) and a portrait of Chief Pokagon wearing a crucifix are the material remnants of these complex relationships—the subtle, purposeful manipulations through which Pokagon band members physically presented themselves as converted in a way that enabled them to keep their land.

Crucifixes and other religious objects are the residues of the attempts of missionaries to spread a religious ideology in the New World, a central goal for many colonizers, especially France and Spain. Many Native peoples incorporated Christianity into their lives, resulting in an important shift in their worldviews. Yet one wonders if the categories of “converted” and “unconverted” adequately capture the complexity of the identity negotiations Native peoples made. When religious ornaments are recovered from colonial-period Native American sites they commonly are interpreted as evidence of missionary activity, perhaps even to as evidence that the Native peoples had converted to Christianity (see Larsen et al. 2001; McEwan 1993, 2001; Thomas 1993). But does the presence of both numerous Christian symbols (saint medals, crucifixes, etc.) and Native American religious elements signify that the owner of these items was on his or her way to becoming a convert? Or should we perhaps reflect on how Native Americans wore Christian symbols in combination with other Native American and European clothing and adornment? Here we must be aware of the limitations of functional categories; Christian symbols can indicate more than religious expression or conversion. The context in which a Christian symbol was worn is crucial; in different contexts it may have simultaneously spoken to other issues such as ethnicity, status, or gender. Was it used as a reminder of faith or used as a charm or amulet? Crucifixes and religious medals held certain meanings for baptized individuals, but rosary beads and other Christian symbols took on new meanings when Native American men, women, and children publicly combined these objects with indigenous items to purposefully and publicly negotiate self in the context of religious conversion.

An example of the complicated use of religious symbols in a colonial context is found at Presidio Los Adaes, the capital of Spanish Texas from 1729 to 1770. Los Adaes was situated along the eastern border of eighteenth-century Spanish Texas, just miles from French Louisiana. The presidio was occupied by Spanish and mixed-blood military personnel and their families as well as civilian settlers from New Spain, French refugees, Caddo Indians, and some escaped African slaves from French Louisiana (Avery 1995; Loren 2001a; Loren 2007b; Gregory 1984; Gregory et al. 2004). I have discussed the meaningful manipulations of clothing and adornment in this multiethnic colonial community elsewhere (Loren 2007b); here I want to focus on the religious items recovered from one house at the site and how they may have been used by the population.

A structure referred to as the “Southeast Structure,” located southeast of the main presidio building, featured a large outdoor kitchen. In 1982, H. F. “Pete” Gregory excavated the structure and recovered numerous artifacts of clothing and adornment: four fabric seals, a scrap of gold lace, a piece of blue-gray woven fabric, collar ornaments for military shirts, a copper brooch, an earring, rings, numerous large and seed glass beads, patterned buckles and buttons, and three tinkler cones (Gregory 1984). The variety of clothing and adornment artifacts found among the households suggests that the occupants creatively configured their dress by combining aspects of European-style fashion, evidenced by the blue-gray wool, patterned shoe buckles, and collar ornaments, with aspects of Native American-style dress, evidenced by the glass seed beads and tinkler cones that were likely sewn onto buckskin clothing (Loren 2001a, 2007b).

The religious ornaments recovered from the household add to the dynamic fashion embodied at the presidio and indicate how religious adornments and amulets were used to promote physical as well as spiritual well-being. A large brass St. John of Matha medal and a smaller Holy

Family medal recovered from the household were likely worn with glass bead necklaces and copper-alloy rings, brooches, and earrings. Amulets, the focus of the next section, were believed to possess magical powers and were also worn in combination with religious items and other items of adornment. Numerous metal higas (amulets in the shape of a closed fist worn to ward off the evil eye and promote health) were recovered from the household, suggesting that residents were anxious about the health of both their souls and their physical bodies (Gregory 1984; see also Deagan 2002). Gregory et al. (2009) postulate based on a peculiar set of artifacts recovered from a cooking pit that one of the house’s occupants was a curandera, or folk healer. A brass wick trimmer, egg shell fragments, and tubular red glass beads were found close to the St. John of Matha medal at the bottom of the pit. In curanderismo, which includes elements derived from both indigenous and Spanish cultures, a female healer prays for spiritual cleaning and protection against evil spirits. Among the items commonly used by a curandera are eggs, candles, pictures of saints, animal bones, herbs, and holy water (Gregory et al. 2009), items that closely resemble those recovered from the cooking pit. The combination of Catholic medals with secular items and amulets found at this household in colonial New Spain indicate how aspects of Catholicism and its associated material culture were woven not only into worldviews and identities of people living at Los Adaes but also into body adornment practices.

Attaching Protection: Pierced Coins

Individuals in many colonial contexts commonly used a variety of strategies to protect their physical and mental bodies. For example, although shoes were obviously used to enclose the feet, in eighteenth-century Massachusetts, European colonists also used them to protect the body in other ways. During a 2008 renovation to the eighteenth-century Han-cock-Clarke house located in Lexington, researchers found shoes in the walls and above the doorways of the structure (Lexington Historical Society 2007; see also Stephens 2010). St. George documents how people placed shoes and other items above doorways of New England homes or buried them beneath the hearth in order to protect the people living in the house from the dangers of the outside world and from maleficent bodies (St. George 1998:188-193). In this way, Puritans assigned magical properties to everyday items. As another example, they filled Bellarmine bottles with urine, hair, and pins to make them into “witch bottles” as a strategy to keep evil spirits away.

These items used to protect the body, oftentimes worn on the body itself, differ from religious medals or crucifixes in that they are not “used as intermediaries between their owner and a higher power” (Deagan 2002:87). Rather, these items are invested with meanings and beliefs that imbue them with power, sometimes magical in nature but always protective of the physical body. Items used as amulets or charms fall into two categories: those specifically made for protection (such as horns or higas to ward off the evil eye) and everyday items put into use as charms or amulets (such as shoes or pierced coins). In this section, I describe some examples of the use of pierced coins to protect the physical body.

Puritans were not the only people that wanted to guard their physical bodies. A variety of strategies to protect the body were used in other colonial sites in North America. Kathleen Deagan (2002:87-105) provides a lengthy list of amulets recovered from Spanish colonial sites in the Southeast, all of which were intended to protect the wearer from illness or to help the individual withstand or bring about certain bodily processes: teething, nosebleeds, hemorrhage, or conception. These practices of using protective adornments often derived from European homelands. Native and African peoples in North America during the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries also pierced or drilled holes in coins and thimbles for the purpose of adornment. African Americans’ use of pierced coins in adornment practices during the late eighteenth and nineteenth centuries is often related to the folk use of charms to ward off evil spirits or illness (Davidson 2004:23; Wilkie 1995). At the Dog River Plantation located in Mobile, Alabama, an 1840 Liberty silver dime recovered from the site may be an example of such a belief system at work (Waselkov and Gums 2000:166).

Davidson (2004) outlines this kind of practice in his discussion of the presence of pierced coins at an African American cemetery in use in Dallas during the period 1869-1907. He (2004:23) notes that pierced American coins were recovered from 15 interments, usually from the neck or ankle region. To trace the origin of this practice among African Americans in the South, Davidson reviewed narratives of former slaves gathered by the Works Progress Administration in the 1930s and folklore collections related to the use of coins as charms (Davidson 2004:23-26). The practice was common among African Americans in Dallas and other areas of the South

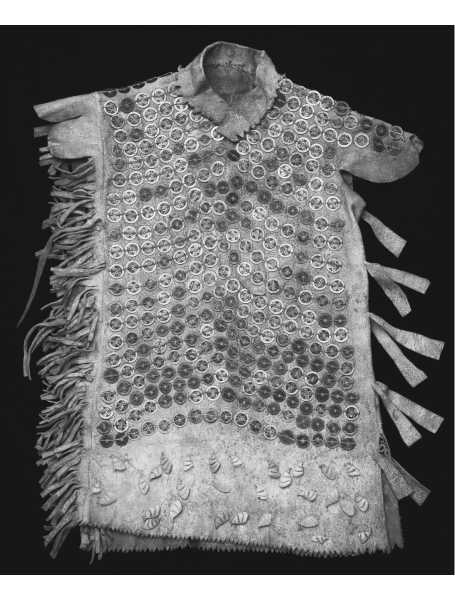

4.4. Walrus-skin coat with puffin beaks and Chinese coins, Tlingit, eighteenth century. Courtesy of President and Fellows of Harvard College, Peabody Museum of Archaeology and Ethnology, 69-30-10/2065.

During the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, when coins were used as charms to ward off evil or protect against health risks. Pierced coins were placed around the necks of young children for protection during teething and weaning, and adults apparently wore them to ward off rheumatism and other ailments (Davidson 2004:37-45).

While pierced coins found within late-eighteenth - and nineteenth-century African American contexts have been related to religious or spiritual practices, the same cannot be said for pierced coins found within Native Alaskan contexts. Too often, the Chinese coins incorporated into Tlingit and other Northwest Coast Indian clothing has not been examined in terms of its use as a charm related to a religious practice. Rather, this material been interpreted as similar to brass tinkler cones or brass janglers used in other kinds of Native American clothing practices. For example, coins minted with perforations that were used as adornment or charms can be found on the late-eighteenth-century Tlingit armor shown in Figure 4.4, which is covered with Chinese coins from the reigns of four consecutive emperors: Shun-Zhi (a. d. 1644-1661), Kang-Xi (a. d. 1662-1722), Yong-Zhen (a. d. 1722-1735), and Qian-Long (a. d. 1735-1796). In this case, the coins used on the armor protected the body of the wearer in multiple ways: coins were particularly effective when worn as armor, and the coins that adorned armor in war and ceremonial settings symbolized the status of warrior (Henrickson 2008; see also Wolf 1982:187).

And what of pierced coins recovered from predominately European contexts? Pierced coins have been recovered from Jamestown (Kelso et al. 1997; Mallios 2000:42-43). Kelso and colleagues (1997:48; 1999:11) suggest that English settlers pierced coins to make items for trade with neighboring Native peoples—that in this frontier place, coins were more valuable as jewelry for barter with Native peoples than as legal tender. These kinds of discussions, however, need to take into account the facts that coin charms were commonly used in many parts of Europe from the fourteenth through the nineteenth centuries (Davidson 2004:26, 29-30; Hill 2007) and that this practice was also followed by people of European descent living in colonial America.

While researching past excavations conducted in Harvard Yard as part of our continuing research on colonial Harvard, my colleagues and I were surprised to find that one of the three coins recovered from previous excavations—a seventeenth-century Richmond farthing issued between 1625 and 1635—was pierced and was likely worn as an adornment (Figure 4.5). Our surprise was not because the coin was pierced, as pierced coins are commonly recovered from colonial contexts, but because this was the first evidence of such items in the context of seventeenth-century Harvard.

In colonial New England, Puritans viewed flamboyant fashion as disorderly. Bay Colony sumptuary laws loudly enforced a modest and conservative style of dress among all inhabitants; a style that would indicate at a glance who a person was by what he or she wore (De Marly 1990:35-38; Goodwin 1999:112). In 1651, the members of the Massachusetts legislature had declared their “utter detestation and dislike, that men or women of mean condition, should take upon them the garb of Gentlemen, by wearing Gold or Silver Lace, or Buttons, or Points at their knees, or to walk in great Boots (quoted in Degler 1984:11). Not surprisingly, the 1655 Harvard College Laws mirrored this orthodox vision of conservative dress, dictating that students were not permitted to leave their chambers without “Coate, Gowne, or Cloake” and that “every one, everywhere shall weare modest and somber habit, without strange ruffianlike or Newfangled fashions, without all lavishe dress, or excesse of Apparell whatsoever” (Colonial Society of Massachusetts 1935:330).

4.5. Pierced coin, seventeenth century, Harvard Yard, Cambridge, Massachusetts. Courtesy of President and Fellows of Harvard College, Peabody Museum of Archaeology and Ethnology, 987-22-10/100153.

Artifacts of clothing and adornment recovered from the fill of the Old College cellar that date to the late seventeenth century (1680-1700) include four metal hook-and-eye clasps, a bone button, a copper-alloy button with embossed decoration, one iron knee buckle, several lead fabric seals (most likely from bales of woolen fabric), and a pierced Richmond farthing (Stubbs 1992:553-554, 558). This modest assemblage suggests that the students likely followed prescribed institutional fashions. The only item that suggests otherwise is the pierced Richmond farthing. Even though college laws did not prohibit the wearing of coins as jewelry, this practice did not comply with “somber habit.” The pierced coin recovered from the Old College cellar suggests that the wearer was anxious about bodily protection, even witchcraft, while being educated at a Puritan institution, where he was being rigorously schooled in knowledge about hellfire, brimstone, God’s wrath, and the dangers of witchcraft.

Seventeenth-century Harvard was a multicultural setting. For approximately 25 years after the establishment of the Harvard Indian College in 1655, English and Native American youths were trained side by side to become ministers (Lepore 1998:32-38; Morison 1995:129). Does the pierced coin connect us to the Wampanoag and Nipmuc students who were being educated at the college? Does it indicate that some of these students chose to embody practices that were more familiar in their home communities of Mashpee, Aquinnah, and Hassanamesit Woods? We hope that our research at the site will provide more answers, but this pierced coin provides us with insight into how seventeenth-century people at Harvard chose to protect their bodies through adornment. Ongoing research may provide more answers on this object and how it was worn, but for now this pierced coin raises questions about how individuals at seventeenth-century Harvard chose to protect their bodies through adornment that went against the grain of institutional ideals.

Several of the adornment practices discussed in this chapter extend into the nineteenth century, indicating the importance of particular adornment practices for many communities long after they were embodied in colonial contexts. As White (2005:1-2) notes, care must be taken not to marginalize small finds in archaeological interpretation by categorizing them only by their function and not examining the context and meaning that items of adornment may have held for the owner. Items of adornment provide us with an avenue for understanding complex issues of identity and the ways that people chose to embody self (see also Deagan 2002; Loren and Beaudry 2006). In the next chapter, I discuss several assemblages of items of clothing and adornment to outline some of the diverse practices by which dress and identity were constructed in a variety of colonial contexts.

World History

World History