When the Europeans arrived in the New World, they wore clothing made of scratchy flax flbers or of wool and were astonished to flnd all the Peruvians, a “primitive race,” wearing soft: cotton fabrics that only European royalty could afibrd. The development of cotton had indeed been a key element in Peruvian civilization. The plant grew wild on the slopes near the coast from Ecuador to Ancon, a site on the Peruvian coast, where cotton bolls dating to 4200 bce were found. It was not the creamy white color favored in modern times, but ranged from yellow to light brown to a dark reddish brown. It was domesticated not so much for cloth as for the manufacture of flshing nets and flshing lines. It is not an accident that next to the cotton plants, the locals planted gourds, which served as floats for flshing nets. The combination of cotton and gourd produced a maritime revolution in that it allowed the ancient shore communities to flsh for larger flsh, and to catch more of them. But this meant that just as the shore communities became dependent on cotton, the cotton producers became dependent on the shore communities for flsh. It was a unique bipolar economical system in which flshing cultures and irrigational cultures were separate, but bound to each other.20

Agricultural goods were, of course, integrated into cotton growing from early on. Manioc, brought down from the Amazon highlands, was particularly important. Prepared as flour, it was one of the leading export items from the Amazon along with herbal medicines. Potatoes of various varieties, though not technically imports since they grew wild in the upland hills and mountains, were transplanted to these lower-lying areas. During this time (ca. 2000-900 bce), we also see the appearance of the flrst ceramics. Ceramic technology did not originate locally in Peru, since nowhere is there any evidence of an insipient tradition. It might have come from the Ecuadorian coast. But most researchers think that it came from an overland route, namely up the Maranon and Huallaga rivers. At any rate, the spread of pottery coincided with the spread of maize cultivation throughout most of Peru during this period, as well as with the appearance of peanuts, all of which is clear evidence of the contact between the Peruvian coast and the tropical lowlands of east South America. The domestication of the llama also took place during this period.

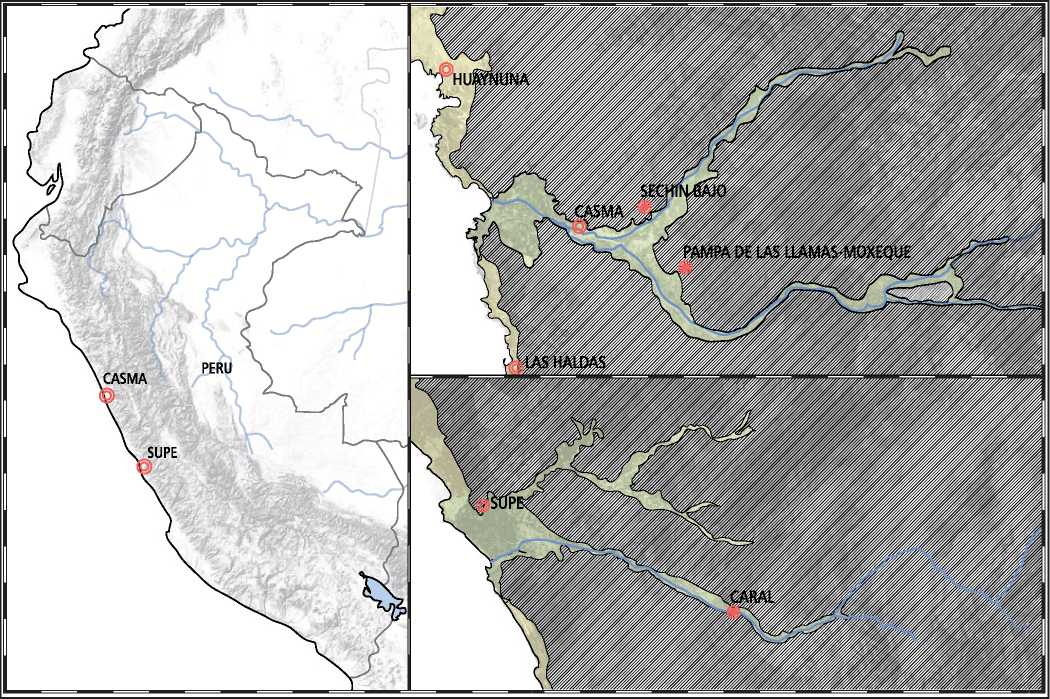

Regarding the history of agriculture, Mexico/Guatemala and Peruvian situations were quite difierent. In Mexico, the shift from plant tending to agriculture took place initially in marshy areas that could be speciflcally exploited for corn production since these were places where the annual resilting of the river protected somewhat against soil depletion. In Peru, the plants that were easily tended in east-facing lowlands, had to be artiflcially transplanted to coastal regions where they had to be laboriously nurtured by means of irrigation systems. Rockslides, floods, and earthquakes continually endangered these systems and on more than one occasion overwhelmed them. The similarity of the Olmec and the Peruvian coast, one extraordinarily wet and the other extraordinarily dry, is that both were places where agriculture was not developed early on. Both were extreme landscapes that required political organization difierent from what people had been used to for the past thousands of years. The new elites did not reinvent the wheel, however. The traditional shaman now became the priests with ceremonies that still made sense to ancient sensibilities. But instead of the shamans going from hut to hut, they had gigantic architectural platforms made for them that magnifled and broadcast their power. It was in this context that we see along the Caral and Supe river deltas the flrst large-scale attempts at organized agriculture (Figure 11.21). The risks were enormous, but must have been well worth it.

Figure 11.21: Supe and Caral valleys. Source: Florence Guiraud

Supe Valley was designed from the start as a major cotton-producing center. Its principal temple was located about 20 kilometers upstream from the sea on a natural terrace 25 meters above the Rio Supe flood plain. Its size (65 hectares) and number and complexity of platform structures point to a powerful elite with extensive resources for construction. But unlike La Galgada and Huaynuna, Caral did not grow over several hundreds of years into a regional center. It had no long clan history associated with it. Instead, it was more or less created ex nihilo by people who knew what they were doing and why. This was a single, corporate-styled endeavor, with much to gain and much to loose. For the flrst time in history a culture was to build a plant economy around a non-food-related material that was also not a building material like stone or wood. In fact, there is no comparable situation where a nonedible plant was moved from its native ecology and placed in an artiflcially constructed one all in the name of an economic gamble on its rising value among the locals.

The Supe Valley is an extreme landscape (Figure 11.22). It almost never rains and is well past the fog zone; the dry mountains of yellow clay run ragged up its sides. Its dangerous floodwaters precluded any settlement. The exact nature of its water management is not fully known, but channeling and calming the water was critical. The other problem was that the cotton plant has deep roots that tend to exhaust the soil and so requires extensive soil management to maintain productivity. The floods certainly bring down mineral-rich silt from the mountains, but even these get exhausted. The difierent centers in the valley are an indication of the search for new agricultural zones. The key to this system was to flnd a suitable place in an upstream area of a river where one can create a channel that diverts the water more gradually along the slope and in this way following the contours of the land bring the water to where it is needed, maybe kilometers away. This requires a thorough understanding of the landscape, its soil and rock conditions. There must be diversion mechanisms for times when there is too much water. At issue is not just the engineering. Someone also has to decide who gets water when. It is, therefore, quite

Figure 11.22: Supe Valley, Peru as it looks today. Source: Hakan Svensson Xauxa (http://creativecommons.0rg/licenses/by/2.O/deed. en)

Likely that the authorities who created the canals, coordinated their use, and maintained their functionality were also the masters of ritual.21

Though cotton and gourds were the main trade items, people of Caral also grew and traded squash, beans, achira, sweet potato, avocado, guava, pacay, lucuma, and chili peppers, all non -native species brought in from the highlands. At its height, around 2000 bce, this entire river would have been a bustling agricultural miracle unprecedented in the world. The several thousand people who lived there did so also in relative tranquility, since there is no evidence of warfare (Figures 11.23, 11.24).

Caral contains thirty-two public structures and though the largest and most complex center is in the Supe Valley there are in fact others, seven in all, with monumental architecture distributed across an area of 7 kilometers, three on the northern slopes of the river (Pueblo Nuevo,

Cerro Colorado, and Allpacoto) and another three on the southern border (Lurihuasi, Miraya,

Chupacigarro). How these polities were run is hard to tell, but it was not based on a particularly powerful center and distant peripheries, but on tightly interconnected ritual centers of differ-

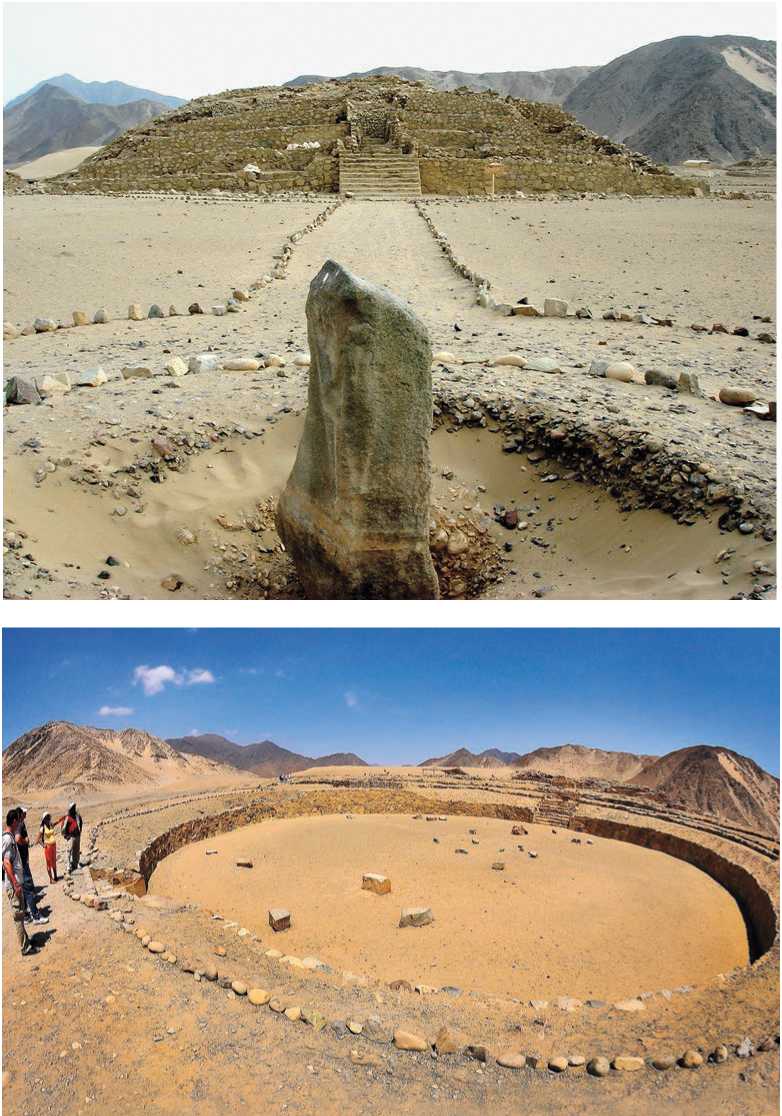

Figure 11.23: Caral, Supe Valley, Peru. Source: Martin Harbaum

Figure 11.24: Caral, Supe Valley, Peru. Source: Daniel Barker (Public Domain)

Ent scales. There were probably three classes of people. The commoners, who did most of the field work and building construction, the elites who ran the economy, and the priests and their associated retinues who provided the calendric and ritualistic ideologies necessary to mobilize the community. Whether the elites and the priests were separate and distinct classes is not clear.

Because of its size, the site is ofi:en labeled a “city.” But this can be deceiving even if the population of the valley might have peaked at 20,000 people. The elites lived in clearly defined districts around the major monuments in houses of adobe, but everyone else lived in reed and thatch constructions in clusters along the banks of the flood plain and up the slopes of the hills or at the edge of terraces. The standard image of a city surrounded by fields does not apply. Here the fields came first, then the terraces needed for the large ritual structures and, only then, the habitations which were fit in between and around them or in places not suitable for agriculture, forming a type of sprawl. How the difierent centers that line the valley operated is not known, but what is sure is that the Supe Valley served as a powerful economic engine—completely novel in the Peruvian context of the time—complementing and radically enhancing the coastal fishing economies while at the same time serving as a draw for interregional trade.

Caral’s huge central plaza was built on a blufi' to visually dominate its surroundings with views up and down the river valley. It is roughly 500 meters by 175 meters in size, and is defined by an array of buildings that include six large platform structures, a range of smaller platforms, two major sunken circular plazas, an array of residential structures, platforms, and buildings whose purposes are not yet known.

Although the ceremonial structure of Caral is called “Pyramid Major,” it is no pyramid, but a series of platforms or, better yet, terraces (160 by 150 meters and 18 meters high) located at the northern end of the site at the very edge of the ritual center. It was constructed in two major phases. First, the walls were built by filling in open-mesh reed bags with cut stones. The outer surface of the wall was then covered with multiple layers of colored plaster. At its southern base there is a circular court 35 meters in diameter that consists of a sunken space with a double ring of 3-meter-high walls. The space between the walls forms an elevated circular platform 7 meters wide. On the north-south axis, staircases descend into the depression, each framed by two large upright monoliths. Another monolith was probably located at the center of the court, although its precise position has now been lost. The walls, stairs, and floors of the plaza were plastered and painted.

A stair leads to the peak of the stepped platform with its panoramic views of the valley. The main doorway at the summit leads to three spaces that continue one beyond the other: (1) the ceremonial enclosure with a hearth in the center and a series of tiered platforms placed at intervals like steps; (2) an elevated platform through which the atrium is accessed, with two rooms, one on each side; and (3) halls of the highest section are presided over by other small platforms. The Small Quadrangular Altar is found to the east of the atrium and contains a central hearth, a fireplace, and a subterranean ventilation duct. The altar is associated with a group of halls decorated with friezes and niches, which are accessed by means of stairs, passageways, and openings. The rooms, altars, and courtyards on top of the terraced mound suggest they had both religious and administrative purposes.

Pyramid Major is part of a cluster of platform mounds that form a C-shaped plaza, facing south. Just beyond its open mouth is another sunken circular plaza, even larger than the one associated with Pyramid Major. It is 50 meters in diameter. If the main plaza, surrounded by mounds high above the valley floor, creates the impression of a vast bounded space reminiscent of a high valley plateau, then the circular sunken plaza, reminiscent of the later kivas of North America, repeats that space on a smaller scale. The main plaza seems to have been identified with human life on earth, whereas the circular spaces below grade may have functioned as gathering spaces corresponding to the lower elements of life with the upper platforms presumably accessed only by the priests. Archaeologists have found no evidence of an invasion or a rebellion. Instead, it seems city residents systematically covered over plazas, pyramids, and other buildings with gravel and pebbles 3,800 years ago and then left:. Their efiorts, plus the region’s dry climate, helped preserve such buildings as the 13-meter-high Amphitheater Pyramid, which was apparently used for religious functions.22

World History

World History

![Road to Huertgen Forest In Hell [Illustrated Edition]](https://www.worldhistory.biz/uploads/posts/2015-05/1432477693_1428700369_00344902_medium.jpeg)